Welcome new subscribers and thank you to everyone that replied to my first post, last week, about WiliWear. I have many more folders of Willi’s work and I’m so glad I had the opportunity to introduce him to many of you.

The Biopolitics of 90s Gaultier – Part 1

Every time I thought I was done with this Gaultier post for Blind Archive the draft would haunt me, “Yea but did you think of ____ in the context of full body printed nylon mesh”...so here’s the first post of what will be an ongoing series.

“For snobs and parvenus and social climbers, [Tuberculosis] was one index of being genteel, delicate, sensitive. With the new mobility (social and geographical) made possible in the eighteenth century, worth and station are not given; they must be asserted. They were asserted through new notions about clothes ("fashion") and new attitudes toward illness.” Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (1978)

Image: Jean Paul Gaultier Two Page Advertisement

[ID- A Black masculine head protrudes from a blue and pink circuitboard patterned background. There is a blue metallic dot-gridded mesh covering his face, this reminds me of custom 3D printed face-masks made for cancer patients to line up radiation machines. Right panel features the same figure, sans mesh, standing square, full figure in a very Matrix-esque outfit, a second figure in a slick black body suit walks towards the centerfold in the background as if on a runway.]

There are few points that I am willing to die on a hill for but one of them has to do with Gaultier. I would argue that the main gift to fashion sensibility made by Jean Paul Gaultier’s body of work from the mid-90’s is not the aesthetic elevation of the club, kitsch and queerness. It is not the revolutionary redefinition of beauty, polish, wealth and power as a messy, layered, androgynous look licensed and disseminated across multiple brands. It is not even Gaultier’s liberation of sheer fabrics to stand alone as their own garments. In fact, Gaultier’s most important contribution is actually the luxury commodification of a phenomena that Sontag calls, “the nihilistic and sentimental idea of ‘the interesting.’”

“Both clothes (the outer garment of the body) and illness (a kind of interior decor of the body) became tropes for new attitudes toward the self.” Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (1978)

Image: Movie Stills

[ID - Two side by side stills from The Fifth Element (1997), left image features a young, muscular, masculine Black person in a dramatic faux fur leopard print long sleeve dress. The dress has batwing sleeves and a wide open neck off-the-shoulder collar. They are wearing a silver necklace with a large silver pendant which has a red stone in the center. Their hair is blond, short and curly, close cropped, except for a large protruding cylinder of hair coming straight from the forehead like a unicorn. The person is wearing a silver, futuristic mic, with arms outstretched, leaning towards the camera and screaming or singing. Right image is a close cropped shot of a young white femme in a white cap-sleeve knitted shirt and orange rubbery suspenders. Their hair is bright, unnatural, orange and very textured with short bangs, parted in the middle and ending bluntly an inch above their shoulders. They are smiling and wave at the camera with their right hand.]

Don’t Worry, These Club Kids All Have Trust Funds

First, I would like to pinpoint this discussion in Gaultier’s Fall Winter 1995 Pret-a-Porter show. The collection was designed in conjunction with Gaultier’s work on the costumes for the Luc Besson movie, The 5th Element (1997) and is widely celebrated as one of his most important seasons. The self-described theme was ‘high-femme Mad Max.’ Also worth noting on background is the casting, FW ‘95 features two very pregnant models widely heralded as a celebration of ‘biologic womanhood’ and a falcon held by an elderly socialite.

Below is an old news segment reviewing the presentation, which gives you a brief, and frankly, hilarious, tone deaf glimpse of FASHION before STYLE dot COM, where runway shows were reviewed on the evening (inter)national news and the brutal production timeline of fast fashion didn’t dominate the market cycle.

[VD - Digitized recorded television segment from an unknown television network featuring a review of Jean Paul Gaultier’s Fall Winter 1995 fashion show with clips from the runway show and commentary.]

“Consumption was understood as a manner of appearing, and that appearance became a staple of nineteenth century manners. It became rude to eat heartily. It was glamorous to look sickly.” Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (1978)

Gaultier, "a repeat offender of cultural appropriation," did not disappoint with FW 1995, and the vast majority of looks feature what are at best boring and insensitive “tribal themes.” Though, I guess, historically speaking, considering Gaultier is just hitting the first cresting peak of tribal motif ubiquity in SS 1994, it contextually makes sense. I will need to do a post about the Hasidic collection in the future, mostly because a lot of those looks are really good, though controversial. Another day…

Image: Jean Paul Gaultier, FW 95 Optic Mesh Bodysuit on Manequin

[ID - A red, brown and white high necked bodysuit with a zipper down the front . The bodysuit is printed op-art mesh with varying colors which give the impression of depth, tissue and muscles under the suit through color hue and value variation. The contours of a female body are heavily emphasized through color and changes in the scale of the dots.]

Kristen Bateman writes about the collection for Dazed Beauty, saying, “While the clothing ranged from Victorian steampunk tailoring to exacting corsets and printed bodysuits, the make-up was even more punkish in its approach, exemplifying how creatives were approaching the idea of all things “cyber” in the ‘90s.”

What is not addressed in most nostalgic tributes to this collection is the absurd relationship Jean Paul Gaultier has to aesthetic gentrification. This technofuturist gritty club collection is the perfect example of that. Arguably Gaultier’s appropriation of club culture is also an appropriation of the aesthetics of working-class leisure and youth. Gaultier pillaged street and club looks worn by actual young working class downtown queer kids in London and New York in order to launder them into international luxury consumer objects.

Like Luxury’s appropriation of streetwear, the origins of these motifs originate in actual worn looks by real people, often styled from primarily cheap, thrifted or handmade pieces. Every nostalgic reminiscence on this iconic collection notes and critiques the bad taste cultural appropriation and use of the words “savage” / “tribal” but then, in turn, celebrates this moment of class appropriation as having elevated an ‘underground aesthetic.’

Image: Jean Paul Gautier FW 95 Look 77

[ID - Model, Shalom Harlow, with long black pigtail braided hair, walking down the runway with purpose, wearing a high necked, long sleeve, printed op-art mesh bodycon longline dress with circles in a pattern varying colors of blue, black, brown, yellow, white, red and orange, which give the impression of depth, tissue and muscles under the suit-like dress through color hue and value variation.]

“The TB-influenced idea of the body was a new model for aristocratic looks—at a moment when aristocracy stops being a matter of power, and starts being mainly a matter of image. ("One can never be too rich. One can never be too thin," the Duchess of Windsor once said.)” The romanticizing of TB is the first widespread example of that distinctively modern activity, promoting the self as an image. The tubercular look had to be considered attractive once it came to be considered a mark of distinction, of breeding.” Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (1978)

Digesting the background for this show always leaves me fixated on one question. Why do we celebrate an aesthetic as being best, more worthy, or more deserving of collection and preservation only in relation to its proportional desirability to the wealthy?

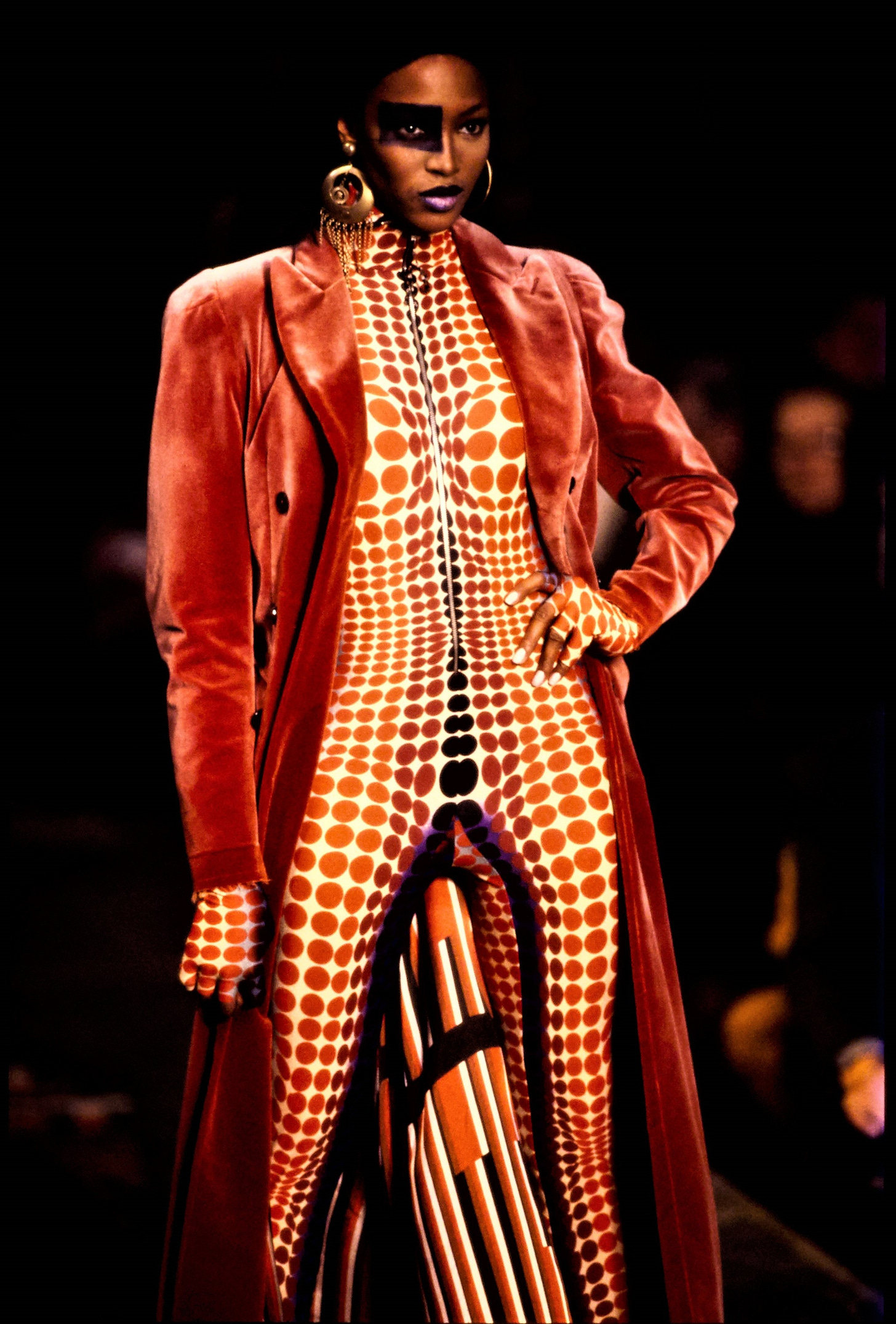

Image: Jean Paul Gautier FW 95 Look 76

[ID - Naomi Campbell wearing large gold circular dangling earrings with a chain fringe and a red, brown and white high necked bodysuit with a zipper down the front . The bodysuit is printed op-art mesh with varying colors which give the impression of depth, tissue and muscles under the suit through color hue and value variation. Over the bodysuit, Naomi wears a red velvet double breasted duster with a structured shoulder.]

“What was once the fashion for aristocratic femmes fatales and aspiring young artists became, eventually, the province of fashion as such. Twentieth-century women's fashions (with their cult of thinness) are the last stronghold of the metaphors associated with the romanticizing of TB in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.” Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (1978)

Image: Jean Paul Gaultier, FW 95 Optic Mesh Dress on Manequin

[ID - A red, brown , olive, orange, blue and white high necked bodycon dress from behind. The dress is printed op-art mesh with varying colors which give the impression of depth, tissue and muscles under the suit through color hue and value variation. The contours of a female body are heavily emphasized through color and changes in the scale of the dots. Legs, underwear and other distinct features are gestured towards with color and pattern as if this is a novelty beach bod shirt but chic. In the center of the back is a very cyber aesthetics square image of a blue head contoured in dots like the dress floating in an olive green dotted void with brighter green around the head.]

The selection of runway models is often one of the most metaphorically important parts of the show as these casting decisions are directly in juxtaposition with social standards of what constitutes an ideal and profitable body under neoliberal capitalism. Gaultier in fact is known for “embracing gender inclusive casting” and was largely lauded in the media for “his support of the LGBTQIA social cause,” which he was also “making chic for the wealthy.” Yet the celebrated inclusion of two very pregnant female supermodels and the resulting media focus only achieved the maintenance of cissupremacist ideologies in the fashion world.

You could design for “all genders” and “all sizes” as a runway stunt, but... try to sell that? At market? No sweetie, you still design three collections a year, two for “thin rich cis women” and one for “edgy rich cis men.”

Mesh as Metaphor

So here we arrive back at the mesh. What does it mean that these expensive clothes are see-through? As much as I appreciate the stunning beauty of the prints and the way they walk down the runway, my stomach churns at the biopolitical critique contained in every facet of these garments' designs. It’s as if they are layer of transparency, tracing the contours of an ideal body through color and pattern with subtle guidelines to see if a body measures “up to standard.”

These clothes are TERFs and that frustrates me not just because it sucks but also because, in an aesthetic vacuum, I really like them. The fact that these incredibly historically important garments have made several friends feel unsafe or depressed to wear is nauseating especially when that is considered in the context of Gaultier’s impact on the luxury market and is, I hope, antithetical to Gaultier’s intent.

Image: Jean Paul Gaultier, FW 95 Optic Mesh Bodysuit on Model

[ID - A red, brown , olive, orange, blue and white high necked bodysuit with a hood from behind on a model who is walking down the runway carrying a suit jacket in one hand. The dsuit is printed op-art mesh with varying colors which give the impression of depth, tissue and muscles under the suit through color hue and value variation. The contours of a female body are heavily emphasized through color and changes in the scale of the dots. Legs, underwear and other distinct features are gestured towards with color and pattern as if this is a novelty beach bod shirt but chic. In the center of the back is a very cyber aesthetics square image of a blue head contoured in dots like the dress floating in a dark grey dotted void with brighter yellow around the head.]

Moreover, in the context of the violent and austere state of trans healthcare, not only in the 90’s but today, these pieces feel like shocking statements, declarations of the strict binary of gender, that under neoliberal capitalism the only bodies which are desirable to the elites are those that can biologically pass as skinny, rich and cis even under the thinnest of printed mesh. It follows that because fashion also must be desirable to the elites in order to sell their products on the market, the end result is actually a kind of creative austerity, limiting in real time how we think about, design, and wear clothes.

Final Thoughts.

How the fashion industry came to be a vacuum like machine, sucking up the lives of the poor and marginalized, turning their bodies into costumes for the rich is a much longer and more complicated history than I can tackle in just one newsletter. The purpose of this series is to share an archive before it’s totally lost to me. I collected these images over 6 years, during which I intermittently (and frequently) went temporarily blind, until I abandoned collecting due to the sheer exhaustion of trying to exist as a chronically ill person in late capitalism.

I look forward to sharing more of my archive with you and more thoughts on the context of these pieces, their relationship to political trends, social reproduction and capitalism, but there might come a time that I need your help to share it.

TL:DR – I am now, quite possibly, permanently legally blind with worsening vision – if you would like to collaborate on Image Descriptions to help me share this archive then please let me know. As we collectively navigate our lives in Covid Year Zero, I think it’s time that we start to imagine a post-capitalist garment industry. Don’t forget, capitalism will also someday fade like many trends before it.

Until next time. Stay alive another week.

Beatrice