Pierre Cardin died on 29 December, 2020. His death is not a tragic one, as so many are right now; at the age of 98, his death was certainly not pulled from the future. And yet, with any loss, you still catch yourself finding feelings, indulging in nostalgia and reflecting on what will be missed by this new absence. I’ve frequently regretted not holding onto more vintage Cardin in my personal collection; the pressures of affording the high cost of my medications over the years has forced me to sell off most of the amazing archival pieces of runway and ready-to-wear fashion that I own (if they are, like Cardin’s clothes, something that can generate decent resale). Good thriftstore luck has saved me more times than I can count.

So, awash in this wave of regret, contemplating Covid (as usual), I went digging through the folders of my archive, seeing if any themes popped out from the many images of his work that I’ve squirreled away throughout the years. What emerged ultimately solidified as three distinct vibes across about thirty different images that I have picked out. Over the next three posts, I’ll share these three thematic collections with you: the first, HEALTH, is below, followed by TASTE and then, finally, MAN.

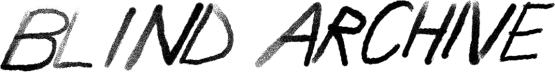

[Image description: Photograph. Figure stands in front of white seamless. They wear a large red patent leather hooded coat. The top has a square hood, like a night’s helmet - tube shaped with a rectangular cut out, showing the eyes. The model’s arms are both outstretched to their side, their hands are up in the air, wrists twisted, as if shrugging and saying who cares performatively while dancing. The bottom of the coat forms a triangle, with its base articulated by the lines of the shoulders as the coat falls over the model’s outstretched arms. The model’s arms and legs are covered in black stockings, boots and gloves, giving the impression of a large, red arrow pointing straight down.]

Pierre Cardin: HEALTH

HEALTH is a selection of Pierre Cardin’s work, across various price-points, which embody the current crisis-warped moment we find ourselves in. As my close friend Charlie Markbreiter recently pointed out, “Now that it’s covid, healthgoth rly hits different lol.” Pierre Cardin really hits different now.

Before Covid, I would have told you a story about how Cardin influenced costume design, about how his ideas changed our concept of total branding(1), about how his vast, licensed, empire was both forward-looking and stuck in time. Cardin’s vision of the future is central to his entire body of work, and foundational to this future is a rigid and playful medical sterility tied into a fantastical and aspirational representation of health. I’ve picked some pieces to share with you that I thought both reflected this theme and could serve as some valuable Covid fashion inspiration. Cardin was after all, a master of unique hoods, face shields, and head coverings—what better for 2021?

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Two people with long hair pulled back into ponytails, wearing black turtlenecks. Image is framed showing them side by side, cropped from the high torso, up. The left figure looks up and just past the camera, and the right figure looks off and up to the left, off frame. They both hold their right arms up and behind their heads forming a sharp angle. Each wears a large pair of glasses, which is also a face shield. The left figure wears a shield that looks like a set of abstracted goggles on the top, with a transparent frame and a darker interior shade. Below the goggle shape is a teardrop, formed the same way, described by a transparent exterior and darker shaded interior. In the middle is a hole for the nose. The right figure wears a shield that is shaped like an upside down “U” creating a large arc starting at the edge of the model’s jaw on either side, and meeting at a curved point at the top of the forehead.]

“The clothes I prefer are the garments I invent for a lifestyle that does not yet exist, the world of tomorrow.” – Pierre Cardin

Healthgoth is arguably part of the aesthetic lineage of fashionable futurism that Cardin pioneered (if you disagree let me know in the comments below I am happy to die on this hill), and much of Pierre’s work actually looks more like something you might see advertised during your endless [soul-sucking] scrolling on the Instagram explore page if you just happen to casually follow whatever chic-boutique-of-the-moment is hottest right now in a low-tier-luxury-adjacent-price-point. Are those cute shades in your feed a rare pair of pret-a-porter eyewear from the 1960’s or a chic SARS-CoV-2 face shield from Covid Year Zero...who’s to say? It honestly doesn’t really matter, this is after all…just…fashion…

Cardin is considered to be one of fashion’s great contemplators of modernity, and through his many multifaceted licensing schemes, he disseminated his interpretation of sterile, healthy, European modernism to the masses. He was the man who put his name on everything. Ambitious and a diligent (albeit nihilistic) student of post-war capitalism, Cardin led the licensing revolution which liberated Haute Couture from its constraints of bourgeois tedium, transforming this elite garment niche into a global branding spectacle.

[Image description: Photograph. Figure in front of a cool blue gradient background. The model’s face is painted blue, with their forehead painted a lighter shade of blue, almost white. Their lips are painted a chalky pink. Their eyes are heavily lidded, with dramatic, dark and thick eyelashes and eyeliner. Over their face is a large oval plastic shield. They wear a white netted turtleneck.]

Cardin’s vision of the future is like if the Bauhaus tended towards a more Pop aesthetic (think furniture in an upscale all-white Manhattan dermatologist’s office). Bright whites, strong black silhouettes, geometry, color blocking, and military-inspired useless details like snaps, chrome buttons, decorative pockets, and non-functional uniform motifs—it’s all in some way or another tied into his uncompromising vision of a clean, vital, and youthful utopia. You can see Cardin’s influence in costume design especially: his work has shaped every visual representation of 60’s era modernism you’ve ever seen portrayed in films and television worldwide. This is not hyperbole, I’m dead serious: you’ll never be able to look at a retro-futurist portrayal of space travel the same way ever again after spending some time with Cardin’s work.

“Modernity, it has to be astonishing. You can’t look back to the past. My clothes don’t get old. They keep getting younger. A woman of 40, who wears my clothes, looks 20.” – Pierre Cardin

The thing that is the most striking to me however, is despite what common fashion-sense would dictate, Cardin is actually right. The 60’s bubbly and bright mod-aesthetic is usually quite dated and cheap looking in practice, but Pierre Cardin’s work is somehow still firmly not. This phenomenon occurs across the board, not just in his most expensive clothes, but down to every last licensed trinket; no matter how minute or insignificant, the aesthetic holds up. Cardin is right: his clothes don’t get old. What gets old is the impressions of his aesthetic, the cultural detritus that comes with it, the gestural template which has been copied, reinterpreted, memed, abstracted and reproduced ad-nauseum in everything from clothing to consumer objects like ergonomic toilet bowl cleaners. The copies are faulty, but the original is in pristine aesthetic condition and often looks more contemporary than what’s coming down the runway today.

[Image description: Book cover, photograph. Figure stands to the right of the picture plane, in front of a white seamless. They wear a round hat with a long/tall/skinny tube sticking straight out the top like a cherry and its stem. Below the hat, the model’s eyes and their curly, short brown hair is visible. Below their eyes is a long blue tube, which is like a large and exaggerated collar, this comes down to the mid torso, extending the proportion of the collar below the line of the shoulders, creating a sort of lapel or bib. The coat itself is a black, mid-legth, well tailored wool coat. To the left side of the picture plane, level with the model’s eyes there is text. Below on the lower left there is text. The text reads, “pierre cardin: fifty years of fashion and design,” and, “Thames & Hudson.”]

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. A figure sits in a white spherical bubble chair. The inside of the chair is fully upholstered in light grey wool suiting. The figure is sitting with their legs sticking out at sharp angles. The right leg is almost at 90 degrees, while the left leg is stretched out with the to pointed on the other side of the bottom of the chair. The model’s waist is twisted so their torso faces the camera. Their right arm is outstretched with their palm resting on their right knee. Their left arm is bent at 90 degrees with their hand on their hip. They are wearing tall black patent boots with flat heels that come up to mid-calf and are seamed from the center of the toe up to the shin with no hardware or laces. The figure wears a heavy grey jumpsuit with well tailored details. The model’s waist is accentuated with a wide black belt with a large square buckle. The model’s chest has a rectangular pin which is etched with various geometric shapes in grey. They wear a complex hooded hat which is shaped like a large gum drop with a circle missing in the center where the face peeks out. Below the chin is one single slit in the hood. The outfit is very reminiscent of the iconic officer uniforms that are worn by the Empire in Star Wars IV, V, and VI.]

For a recent episode of Death Panel, Artie and I sat down with Leslie Lee III, Jack Allison and Tim Faust to talk about Cyberpunk 2077. Early in the conversation, we touched on the visuals of the Cyberpunk world, the “vision of the future” it presented. As Leslie pointed out, Night City and it’s characters were not a vision of the future at all but a neon-soaked, dense, oppressive retro-futurist aesthetic forever trapped in a 1980’s understanding of form, color and texture. (It’s a really great interview, listen to it here.) Leslie’s point has stuck with me in particular as I’ve been digging through Cardin’s decades of work. Contrasting Cardin’s vision of future healthcare (elite, clean, designed, spa-like) with Cyberpunk’s police-force-like Trauma Team (armored, anonymized, aggressive, militaristic) has made me consider just how much Cardin’s idealized medical aesthetics have creeped into the look of our own care system currently in crisis.

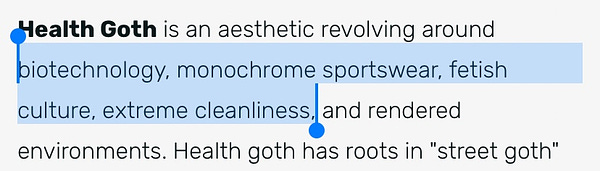

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Three figures stand on a foggy and rocky cliff, which faintly resembles a moon-like eerie landscape. Two of the figures stand to the right on their tip toes in a line facing the camera. Both figures on the right have their arms flat at their sides with their wrists turned up and their hands tightly flexed out as if they are mannequins. Both have their chins tucked and their gaze is at their feet. The second figure is slightly behind the first and only half visible. The third figure is towards the left of center, closer to the camera in the picture plane. The third figure seems to not be subject to earth’s gravity. Their feet are squarely planted on the ground, they are in motion, turned to the side to face the camera and twisted with their arms straight and outstretched in front of them, fists tight. They are bending at the knee, almost at a 90 degree angle and appear to hover in mid-air above the ground. All three figures are wearing white cone hoods with white short-sleeve minidresses and white kitten-heeled gogo-boots. The hood has a half circle opening, showing the models’ eyes, with a straight line across the forehead, connected by a curved window coming to an arc just below the models’ nose.]

Unlike the washed-up 80’s look of Cyberpunk, and unlike the costumes inspired by Cardin’s own work, his designs feel like they are from a world that makes sense with our own contemporary moment. Cardin’s designs would not strike me as out of place within the fanciest, most state-of-the-art medical facilities that I’ve had the privilege of receiving treatment at over the years, facilities punctuated by sterile, biomedical aesthetics, under the oppressive fascist fantasy of health. This biologic fascist fantasy of health, has lately come to be more tangible as only a visual representation. The appearance of health takes precedence over a real-physical manifestation of biological or psychological well being, superseding positive health outcomes as the final goal. I keep returning to the fact that his coats in particular feel as if they were inspired by our own viral pandemic, though designed decades prior in response to anticipated changes in the environment and weather … mimicking the silhouette of a hazmat suit but make it fashion.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. A figure stands inside of an empty underground roadway tunnel. The figure wears a stark white coat which is sort of shaped like a large white traffic cone missing its base. The face gently peers out from an oval hole in the middle of the dramatic hood which makes up the top of the cone space. The hood is separate from the coat, with a large white fox fur trim. The model wears white gloves and white stockings, though the stockings are covered by a shadow from the coat. The figure stands relatively square to the camera, with their torso twisted slightly, their right shoulder rolled back slightly.]

Depictions of modernist-futures often present a sterile facade which seeks to hide the very ugly (often eugenic) truth behind these aspirational aesthetic upgrades. As Charlie later pointed out to me while reviewing an early draft of this essay, aesthetic tropes of “modernity” are part of an elaborate post class fantasy which relies on the lie that technological innovation alone can achieve equity for society. It’s the same counter-insurgent logic that guides political reforms meant to undermine solidarity and disrupt the demands of constituencies by offering them pacifying scraps of policy which fail to address issues at their root cause “Modernity is not good for everyone and was at some ppl’s expense,” he wrote, in reply to Cardin’s assertion that modernity, categorically speaking, must always be astonishing. The “new normal” is just the same old “crisis of modernity.”

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Close up shot of a female face inside of a round plexiglass face covering. The image is very grey, with deep shadows. Her clothing is not very visible but it appears that she is wearing a high grey wool collar of some kind. The short cropped haircut that the model wears nestles perfectly within the clear sphere helmet, with strands gently brushing up against the edge of the bottom opening. There is a high shine on the front of the helmet, which is reflective, in the reflection, a bent forearm is visible, wearing a light grey contrast knit long sleeve.]

Crises are always a moment for society to problem solve, and these next few years will be weird. There is no other way to put it. While Cardin was an unabashed elite capitalist until the bitter end, and most of his work, like that of many fashion designers, exists solely to reinforce racist, ableist, and classist hierarchies through the viral reproduction of rigid aesthetic boundaries, there is something there worth mining and repurposing in our visions of how to decommodify and desegregate our systems of care without compromising aesthetics. Our current brutal reality is being exacerbated by a limited sociopolitical imagination, and we are constrained by a too-narrow understanding of what is possible. It does not matter what Medicare for All costs: we need it. All medical facilities should be as clean and beautiful as the most elite institutions which exist to provide premium healthcare for the wealthy. Rather than striving, full speed, towards a nostalgic ideal of “normal,” we must embrace crisis as a moment for profound struggle, and allow ourselves the imagination to consider what fashion, medical aesthetics, and care could be like after capitalism. Do we really want to waste the next year wishing that things could be as they were before Covid, instead of wondering how they might change for the better because of this crisis?

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Figure’s face peeks out from inside a round portal which is part of an elaborate hood. Shaped like a cylinder the top of the hat comes to a nice blunt ellipsis, with a widening base to accommodate the oval portal where the face peeks through. The bottom collar of the hood is a circular poof of white fox fur which delicately floats suspended over the line created by the shoulder of the coat. There are large white fabric covered buttons. The figure’s right hand is visible in frame, covered completely by a stark black glove the figure cups the right side of their face making a curved gesture with their hand, thumb gesturing towards where the chin would be under the hood, and fingers resting on the hood where the temple would be.]

Looking at these pieces, and considering Cardin’s work, while also thinking about how to leverage and reappropriate health as a means of playing havoc with the political economy has been a productive exercise. It reminded me how strong a role aesthetics has to play in our collective image of “health”: aesthetics, after all, was a central foundational force of the Eugenics movement(2). Understanding and thinking about how clothing and fashion will work after capitalism is an important and often neglected part of the same political space as thinking about abolishing private property and wealth. Fashion after all is one of our most powerful systems of control, an incredible tool in, what Dean Spade calls, systems and institutions of subjection:

“I use the term “subjection” to talk about the workings of systems of meaning and control such as racism, ableism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia. I use “subjection” because it indicates that power relations impact how we know ourselves as subjects through these systems of meaning and control—the ways we understand our own bodies, the things we believe about ourselves and our relationships with other people and with institutions, and the ways we imagine change and transformation. I use “subjection” rather than “oppression” because “oppression” brings to mind the notion that one set of people are dominating another set of people, that one set of people “have power” and another set are denied it. …[T]he operations of power are more complicated than that. If we seek to imagine transformation, if we want to alleviate harm, redistribute wealth and life chances, and build participatory and accountable resistance formations, our strategies need to be careful not to oversimplify how power operates. Thinking about power only as top/down, oppressor/oppressed, dominator/dominated can cause us to miss opportunities for intervention and to pick targets for change that are not the most strategic. The term “subjection” captures how the systems of meaning and control that concern us permeate our lives, our ways of knowing about the world, and our ways of imagining transformation.”

– Dean Spade, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law (2015)

So I return then to the fact that Pierre Cardin put his name on everything. The sheer scale of the branding and licensing operation that this man helmed during his long and prolific life is inspiring. Not for the ability to generate profit, but for the commitment to totality of an aesthetic.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Seven figures lines up next to each other in a row inside of a hospital room. The two outer figures are standing while the five on the interior are sitting. Six of the figures are dressed in all white nurses outfits with unusual matching hoods and hats, Pierre Cardin, the lone masculine figure, is the far left seated figure in a dark grey suit.]

Cardin’s mass market home-sew patterns were as edgy as his runway looks, and often-times much more chic as a result of being spared trendy production with the latest tacky fabric technologies. This type of total branding, while currently the main driver behind the never ending consumptive cycle of retail, should be regarded more seriously as a spear which could pierce the shield of capitalism if appropriated. In our society, aesthetic consistency or pleasure is treated like a luxury. Things that are considered to be luxuries when demonstrated in abundance become visual signifiers of elite status. At the end of the day, these visual signifiers reinforce class hierarchies, making one’s socioeconomic resources readily apparent in order to label and distinguish someone as “important” or “powerful.” What is fashion other than a visual representation of subjection?

Ultimately, this translative process is a simple system designed to reinforce the various imaginary borders which uphold institutions of power by reproducing ideas about the visual qualities of private property and determining the value of human lives through analysis of an individual’s relation to various aesthetics. Health too, which as a biopolitical concept is not just physical but also aesthetic, is tied into and subject to this complex system of visual signifiers. You can tell how well a hospital is funded and how rich it’s chairman of the board is by simply spending five minutes loitering in it’s lobby. To truly undo capitalism, we cannot leave aesthetics for later, it cannot be treated as an afterthought; the decoupling of fashion from elite status as a signifier is as powerful a tool against these structures of subjection as it is a cornerstone of upholding the status quo.

(1) “To survive, haute couture must be built on a pyramid model: haute couture at the top, followed by ready-to-wear, perfumes and accessories, in other words from an exceptional product down to items which can be bought by the general public,” — Julie El Ghouzzi, director of the Centre du Luxe et de la Création (AFP 2009).

(2) For further reading on this relationship between eugenics and aesthetics, I recommend Modernism and Eugenics by Marius Turda (2010).