Known-Unknowns or: How to Spit the Taste of Your Own Death Back at That Which Seeks to Sustain Itself Through Your Annihilation

An update on my drug denial and thoughts about what comes next as I prepare to start a new medication, with still no resolution on my appeal

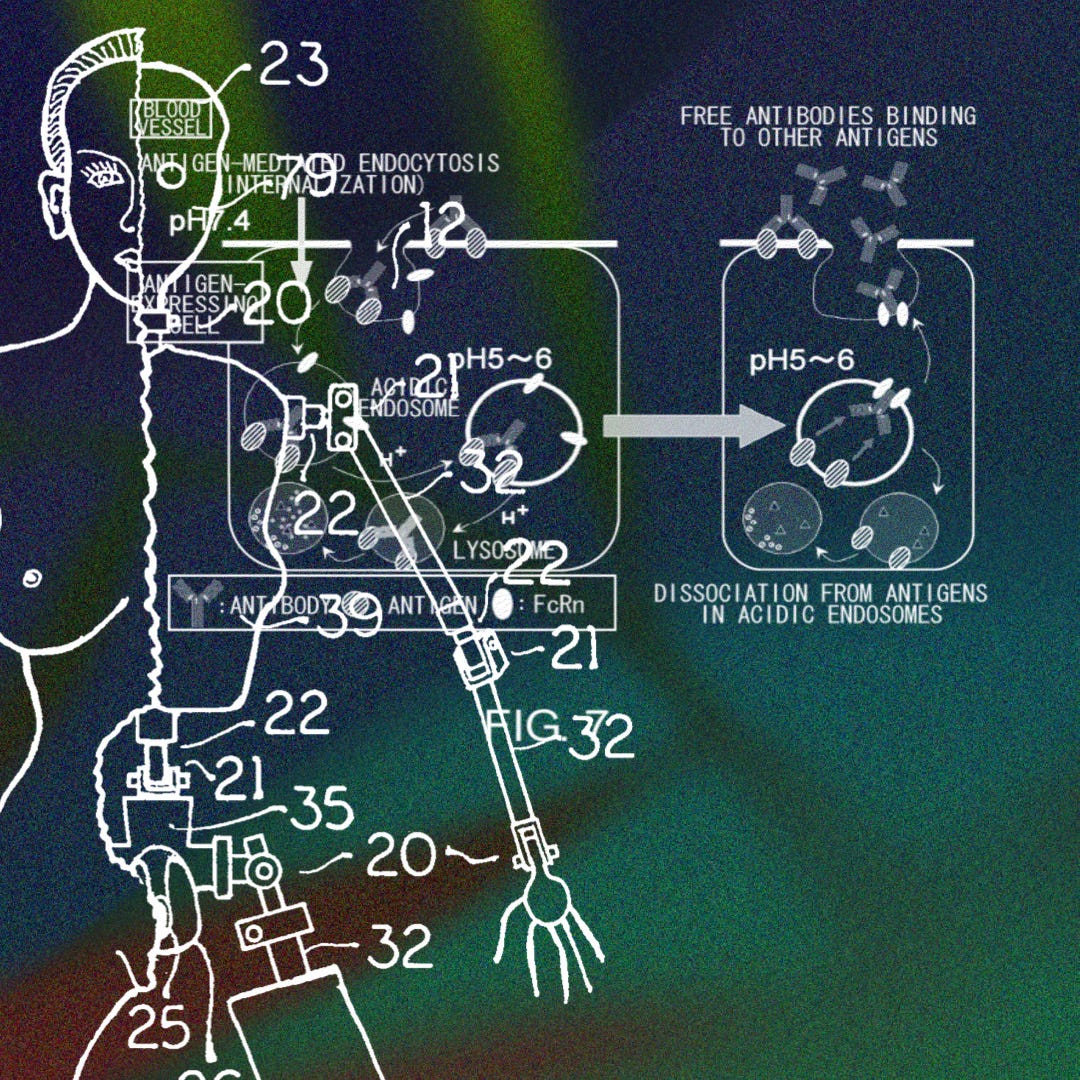

[Image description: two patent drawings over a grainy colorful background. the lines of the drawings are white. The first drawing is on the left and is for a robot, the second is in the top center and is a diagram showing one part of the mechanism of action for a monoclonal antibody therapy. the background is blue, teal, and dark red.]

"It is not true as the philosophers of pessimism say that ‘the dreadful has already happened’ (Heidegger) but it is true that we are haunted by the dreadful and it is true that there is no hope. There is only incessant, unrelenting struggle and that is the permanent creation of the hoped for…"

— David Cooper, “The Invention of Non-Psychiatry” from semiotexte, Vol. III, No. 2, 1974 (emphasis original)

Hello everyone it’s just me, Beatrice checking in after many months with some rare “personal news.” In 60 minutes, I’ll be starting a brand new treatment for my disease. While I wait for the medication to come to room temperature, I’m going to try to get some thoughts down on paper to share with you all. When the timer goes off, and my medication is ready, I’m going to hit send on this newsletter. I hope it finds you all as well as one can be these days during such brutal genocidal times.

First, I want to thank everyone for the support this last year, and second, I want to offer an update. I get asked about what happened to my IVIG infusions and that drug denial at least several times a week, so I thought I’d take five minutes and write out some thoughts for anyone who is interested in knowing what’s been happening with last year’s still ongoing, unresolved medication denial.

I’m checking in because I start a new (different) medication today and I am very apprehensive. It’s a monoclonal antibody therapy but not one I’ve ever tried before called satralizumab. Satralizumab is what is called in the United States a “first-in-class medication” meaning that it’s basically a prototype—this is not a regulatory category, but the FDA does put out a list of these every year and it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s for a rare disease, for example the 2022 list featured the Type 2 diabetes drug Mounjaro (tirzepatide).

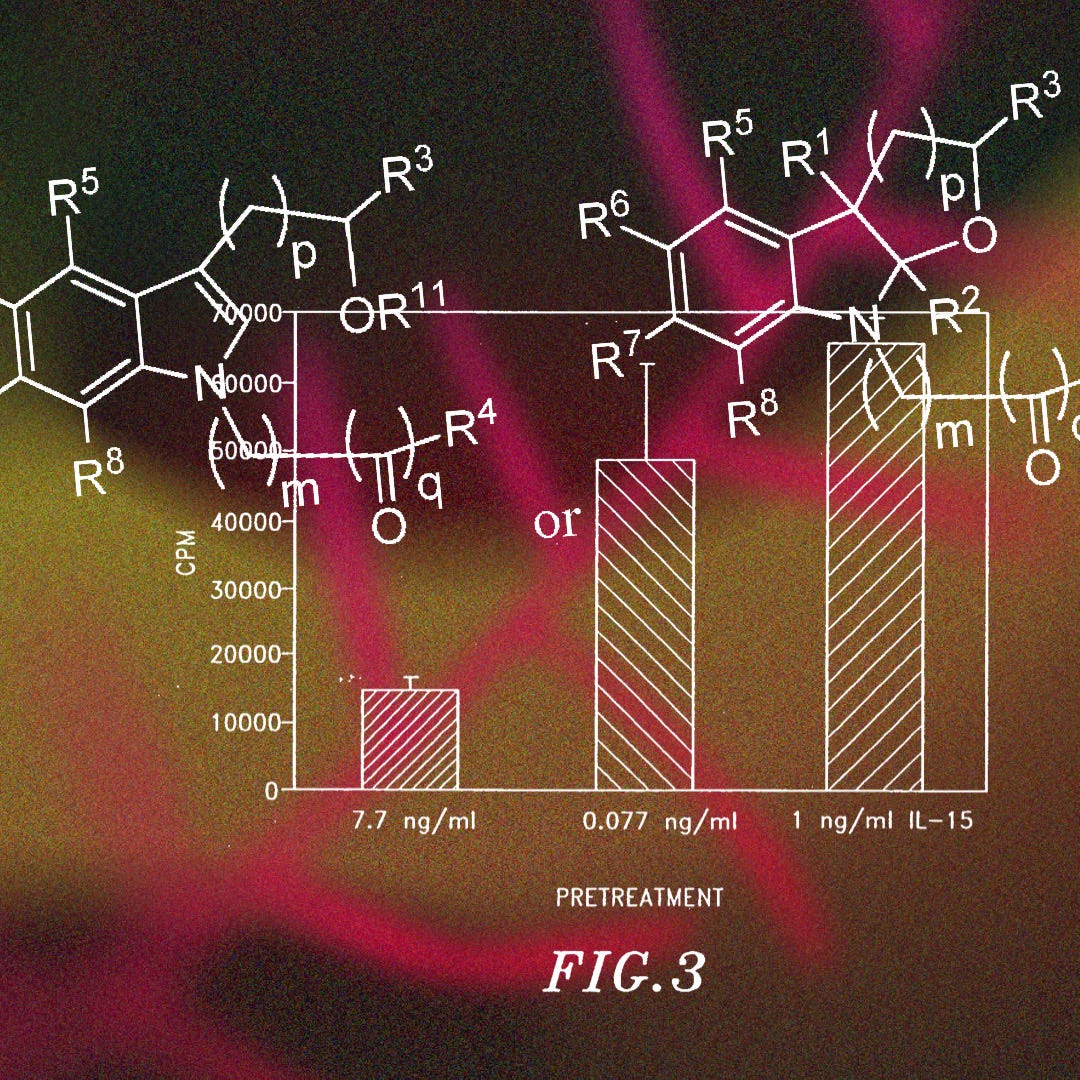

The FDA approved satralizumab based on evidence from two clinical trials of 116 participants total and it was fast tracked through the approval process for drugs to treat orphan diseases. It is currently only accessible to people in the U.S., European Union, Canada, Japan, and Switzerland and only for one disease.

That said, the technology for monoclonals in general is not new. There are lots of different monoclonal antibody therapies out there. Monoclonals are just a way to basically describe the delivery mechanism of a class of drug, it’s the name for a type of protein that is made in a laboratory and designed bind to certain targets in the body, such as antigens on the surface of cancer or immune cells—each is designed to bind to only one antigen, so each drug is very tailored to the specific diagnosis.

Monoclonals are like an envelope, they carry drugs, toxins, or radioactive substances directly to cells and in theory this is materially what people are talking about when discussing the current renaissance of “targeted” medicine. Monoclonals are one of the fastest (and most expensive) growing categories of pharmaceuticals and few countries have any laws allowing or governing generic production of monoclonals—one of the last remaining gray areas of intellectual property law.

I’m lucky to get this drug but I’m still wary of what I know I don’t know about how this will go once the drug is in my body. I’ve jumped through all the administrative hoops, done all the research, read all the available data that has been collected and analyzed. But, will I be one of the lucky ones to get back to baseline? Will I be part of the yet-luckier minority that has regained some of their lost vision? Who knows…it’s not like statistical analysis can truly describe an individual experience of a drug or an act as a reliable measure of expected personal efficacy.

Tempering my hope on purpose might seem pessimistic but this is how you hope long term when there is no hope. Why not lean into (toxic) optimism at the prospect of a drug that might fix my main disease process? Because if it works (and it might not work), and I get everything and all I’ve hoped for, then I am still going to be begging the private insurance system for access to this pharmaceutical property, my maybe-cure, on a regular basis. I will still be chronically ill, disabled, just with one symptom (albeit an important one) potentially under control. And, it’s important to always remember that for me “cure” means immunosuppression with all the limitations that entails. Further, I’m not sure what the drug itself might do to my capacity, what additional side effects might become a part of daily life.

Covid will still be an extra problem, though technically the vaccine should work better in my body than it did before, I’ll be more vulnerable to upper respiratory infections in general. Another known unknown that will only be resolved in due time, likely with a so-called “natural” experiment: There’s no one studying how exactly the vaccine efficacy works in people on this drug specifically. A better answer is again, who knows, I certainly won’t be changing any behavior because even for folks who are fully vaccinated and boosted and not immunocompromised, Covid is still very much a problem. I am not unique in my vulnerability.

Today I’m preoccupied, I guess writing to you all is a kind of self-preserving procrastination. I’ve been checking and double checking my preparations to do my first injection in a few hours—my only weapon against the known-unknowns is a short instruction booklet. I've read all the instructions, the medication is still safely nestled in its ugly little box inside my refrigerator. It’s all there, it’s not broken, I have all the supplies I need. Running through the steps to warm it up in my head like I’m memorizing lines for a play, then the steps to prepare the site, to dispose of the pre-filled syringe. It’s not anything I need to think about, I’ve been doing home injections of medication for years but going over the directions is just something else to thing about. This is what avoiding direct engagement with a specific focus of hope looks like as a consistent practice of sustaining struggle.

I am focusing on all these details because I’m not entirely sure I’m ready to start this drug, despite being desperate to start as soon as possible—I promise you all that I am going to do it as soon as I send this newsletter out <3

I know I am ready, and I am desperate for treatment again, but I am also apprehensive, like anyone would be about all of the unknowns, and with such high potential for let down. Frankly, if it doesn’t work, I’m not ready to be let down by another “miracle drug” that does not work for me—I just got over giving up on Rituxan in 2021 because it wasn’t working. Focusing on the pointless details of the preparation helps me take a step back from the thing that is really bugging me: I’m really not sure how this is going to go and I have to be ok with that.

I am both excited and apprehensive. Other sick people will know the feeling of a new medication and why hope sometimes hurts. I am trying to get comfortable with not knowing how this new drug will make me feel, and the terrible feelings around the reasons why I’m starting this now and not restarting the medication I have been fighting to get back for the better part of a year. (Sieze pharma and abolish private insurance pls and ty!)

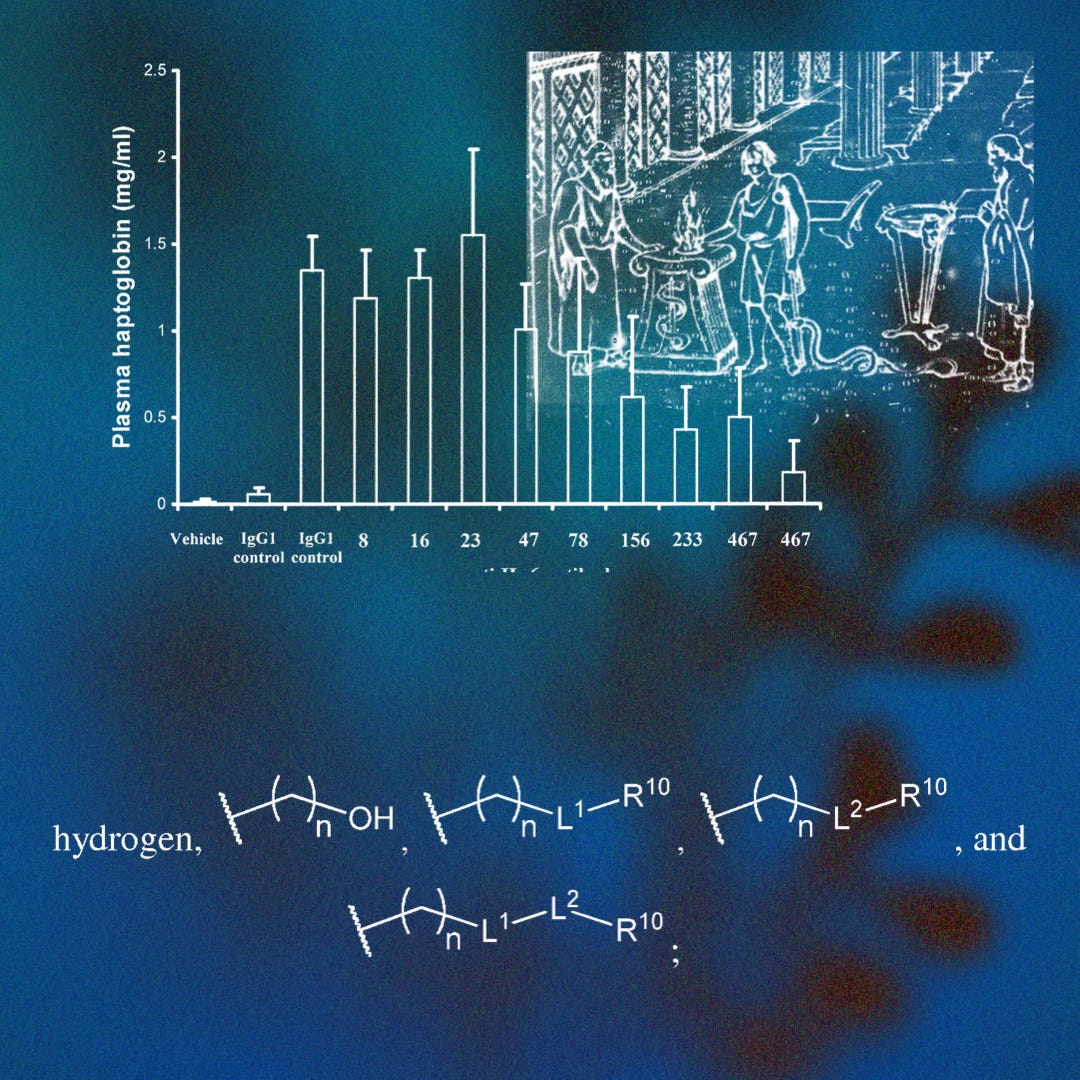

[Image description: two patent drawings over a grainy colorful background. the lines of the drawings are white. the first drawing is a chemical diagram and in the left foreground. the second drawing, labeled figured 5, which is a large table from a patent application. the background is mostly red with pale green and yellow]

When known-unknowns range from useless to cure, life-changing to potentially dangerous folly/waste of time and money, you need to do the work in advance to protect yourself from both disappointment and hope. In a few minutes I am going to take my first shot, then in two weeks I’ll take my second, after I wait and see what happens to my eyes over the next six months, taking the shot once a month. It’s kind of anti-climactic to start a new drug, very hurry up and wait, and the mix of hope and impatience is often equally devastating as exhausting.

For months now I have been waiting, waiting without the medication that has controlled my disease and without any timeline for getting back on it. I have gotten by with managing my stress and the amount of work on my plate, shutting down to rest the moment I feel that characteristic pain in my optic nerves that alerts me to a potential ongoing flare. That was never necessary before with my old medication, and I have been on it so long I wasn’t even sure that managing my disease by the seat of my pants was even possible.

My Medicare Part D plan forced me to find out, after the medication—an expensive monthly infusion—had been covered for 13 years it was denied early last Spring. Though this happened in 2020, I was able to resolve it by moving to a different state, this time I had no such option before me. Suddenly for the first time since I started immunosuppressants in 2009, I was without my main medication for months, which, even in the best of times, was still not enough to keep me from having ongoing symptomatic flares that each took pieces of my vision with it. I’m surprised things were not worse.

The drug denial alone was pretty fucking terrifying but then, it did get worse. After the drug denial, I had another attack of symptoms, resulting in vision loss in late May of 2023, still no medication on the horizon and at that point only on the second stage of my denial appeal. It was the beginning of a long and hard summer. I got some color in my vision back and promptly lost it again, got all the way to round five of the appeal, it was crushing. After exhausting all of my appeal rounds, I entered the final one in late summer and am still waiting for the determination. In some ways the outcome of this denial doesn’t matter as much anymore, but that’s only if the new drug works. If it doesn’t I’m back to square one.

This year has been the worst year of my life physically speaking. I wish I was exaggerating. (Apologies to everyone I owe an email, text or a draft back to especially you, Zachary!) I went from dealing with the heavy side effects of my infusions to dealing with the side effects of not having them: uncontrolled disease. I regained my color vision somewhat in the early-early Spring of 2023, then lost it again by May. My mobility was reduced, my capacity was reduced, and my remaining excess time and energy were redirected to a seemingly endless bureaucratic fight. I know it sounds unbelievable, but nearly a year later, the drug denial is still in the end stages of the final appeals process with no word as to the final coverage decision.

Many people just assumed that I got access to my medication again months ago because it seemed like such a cruel and egregious denial that it wouldn’t stand long uncorrected, and typically these things do only take a few months not an entire year or longer to work out. I also think most people assume that when you’re disabled and on Medicare, certified as deserving by the state, that you can then at least get access to the treatments your doctor prescribes you. Not so much the case unfortunately.

The confusion about if I had fixed my drug access problem yet or not was aided by the drug denial resulting in a reduction in my capacity which required me to withdraw from social media, write less, and just generally have less energy for all aspects of social and public life—so it’s not like people were hearing from me about the day to day of how this process had been playing out so many months later.

I’m sorry I didn’t have the capacity to keep in touch and I hope you all will especially forgive me for not having the capacity to write much about Covid this year—though I was able to produce more than 60 hours of podcast coverage of Covid with my Death Panel collaborators, writing has been difficult. I know some people have felt betrayed by my lack of writing this year because they let me know that they did, repeatedly, via email, and I hope those folks eventually realize that I was still doing that work but in the only format that has been accessible for me to work in—talking.

I still don’t have access to my old medication. I still have no idea if I ever will again. I hope after today the result of the appeal will be irrelevant, and I hold so much hope that this new drug might work for me, but I have no idea if it will be capable of replacing the old treatment. In my heart of hearts I hope it does work, and this long denial and appeal had a point, but I’ve been chronically ill for a long time, and I know better than to get my hopes up without sufficient evidence to back that up. I am very aware that my experience navigating the oncoming known-unknowns will become part of that evidence for others later down the line, which in some ways just raises the pressure that this will work. If my disease can go from non-existent to an FDA approved drug in 15 years, then I hope others struggling with no or mis- diagnosis will experience the same.

The strange cruelty of this drug denial had a silver lining (perhaps a first when it comes to drug denials): without the denial I would not have gotten what I needed to access the new drug I’m starting today. It turns out that with my medications withheld by the petty technocratic greed of the U.S. private insurance regime, I got so sick this year that I finally have that elusive positive biomarker proving my disease and a new formal diagnosis. I’m not really ready to talk about it all just yet, but it’s a fascinating story and it has been strange. Finally, after over a decade under the thumb and control of the whims of the medical industrial complex with no legible credibility as a patient, I am finally imbued with an official certification of legitimacy and conferred the requisite “belief.” It has not made rude doctors less rude or less ignorant, but it has given me access to a new drug—a better drug for me than the one still stuck in approvals, or so the data suggests.

[Image description: two patent drawings and an etched reproduction of an ancient Greek carving over a grainy colorful background. the lines of the drawings and the etching are white. the first drawing on the bottom is a chemical formula, then in the center on the top is a chart and on the upper right is the etching of the Greek carving depicting a cult of Asclepius healing ritual in which a snake licks the wounds of the sick. the background is dark blues with some red and purple.]

I have had the same blood test that produced this biomarker evidence done nearly a dozen times since the test was FDA approved a few years before the pandemic began. The test needed to hit market to find people to test the drug on, which received its fast-tracked FDA approval in August of 2020. However, I had never had this blood work done while my disease was uncontrolled—until this summer in the midst of this draconian drug denial. Every time in the past this test had been run, nothing came of it. It’s the kind of test where you can only test positive, or “not detected,” there’s no hard negative result. Still, though we don’t think about most diagnostics this way, that is not an uncommon conceptual frame—even Covid rapid tests are this way, as per their FDA approval one negative is not a negative and the proper use demands closely repeated testing. Going into the bloodwork this time, I confidently reassured my new neurologist (who was refusing to help me access the drug being denied by my insurance) that there was no way it would be positive. I was wrong, and now I have the new drug.

So that little positive biomarker (and the follow ups that confirmed its not a false positive), after dozens of blood work showing nothing, is now my saving grace and why, even though my old drug is still caught up in the appeals process, I have the opportunity to try something new starting today, something that just might even be better. But then my brain reminds me that its a new drug, for a rare disease, only tested on a small group of patients, and fast tracked through the approvals process, which is taking on a lot of uncertainty and unknowable risk. But what choice do I really have? I am grateful for this new medication, but the choice was made for me, guided not by what was best for my care and for me, but by what made actuarial sense for my insurer. The circumstances invoke a certain base level of discomfort.

But just imagine for a second, where would I be without that bloodwork? I would still not have my medication, and no new drug would be available to me. The part D plan should be held responsible for deliberately destabilizing my continuity of care, just to shave a few thousand dollars off their bottom line. Unfortunately, our political economy is specifically engineered to protect the insurance companies, not you and me, whose bodies are bled for profit as a regular practice of doing business.

I’ve been sick for a while, “haunted by the dreadful” for more of my life than not—but having no hope for cure or a return to being a “normal” person doesn’t stop me from continuing to struggle, even though resigned continuation itself is the most tangible expression of hope you might ever get from me regarding my disease. That might be confusing but I think other sick people will know what I mean.

Put another way: I’m not totally sure that I can make “healthy” people understand what my position on this new medication is. That is, at least partially, because I don’t think there is a lot of room or space in our society to sit with illness and sick people at our own pace—and that limits the attention-span that “healthy” people have for illness narratives that don’t resolve in either death or stabilization. I think Mira Bellwether, who died on December 25, 2022, said it best when someone quoted a tweet of hers about her cancer diagnosis with a trigger warning that read “cw: c*ncer.” Mira said:

I’m going to be blunt:

this shit is the problem.

Me having cancer is a medical truth not a key word for you to avoid because of your feelings. Imagine my feelings! But more importantly:

My survival may depend SPECIFICALLY on many of you NOT turning away!

Please don’t say anything bad to this person I think I understand the impulse. But I am so serious when I say that I need people to not look away from me for having an internal cancerous growth. I need financial help, friends, that’s why a fundraiser is my pinned post

On a more personal level it really REALLY sucks to be told you’re a trigger warning cause but particularly when you’re watching yourself lose weight at an unhealthy speed and you’re throwing up all the time. I feel very ugly a lot of the time just from cancer.

Whether I like it or not I’m a femme and it is HARD to be a femme trans woman watching her body fall apart from illness. I sometimes wonder if i’m still me.

And still, I am actually very sorry to have given anyone cause for fear 😪

I watched my father and my grandparents die of cancer and it messed me up. I never planned, in my mind, to live past 50 just in case. But it was my luck to get diagnosed at 39 when - I must assure many of you- I still feel very young when I’m not utterly ill.

Please don’t turn away from the sick or even the dying. There are lessons we have to teach that some of you NEED about the brevity of life, about the importance of living fully, of not putting off your happiness until later.

And we need you.

—Mira Bellwether, 11:23 PM · Oct 30, 2022 (bold emphasis added)

Mira was right, she is right. Do you think you can make yourself listen the next time someone sick or dying has something they want to share with you? Instead of turning away? Not everyone can, and frankly it’s their loss.

I don’t read Heidegger much anymore, but I used to and I’m going to talk about his work for a second for those who may not be familiar with his conceptualization of the phenomenonology of illness—I promise this has a point other than just being really fucking didactic. To Heidegger, illness is the most intense manifestation of “being-towards-death” (Sein-zum-tode), not a bad thing but a proximity to possibility that he argued is beneficial for both the ill and well alike. Death is a kind of singularly universal possibility, and chronic illness is a way of being that has a special hold on time via being in the world with a closeness to the possibility of death. Illness is being-towards-death not because of any intrinsic quality of illness but rather relative to what is gained by the perspective of illness—a temporal grasp of mortality or “finitude” that is much more material that someone who embodies a perspective which has a different relation of being to death.

In his formulation of “being” (Dasein), Heidegger explains, “Dasein is always what it can be and how it is its possibility,” basically meaning that “being”—conscious existence—is constitutive, constructed, maintained—not a static collection of attributes like objects that we each collect to construct a stable self. Illness is not a property I have, not an attribute, it is the way I can be. The only way I can be, in fact. Illness is my “is,” my possibility, not just my being-towards-death but my whole being itself. That’s not sad, it just is what it is, it is what I am. What that means and what knowledges that can offer to the sick and well alike (as well as what I can offer myself) changes with shifts in epistemology, resources, class, debility, access, technology, built environment, sociality, political economy, etc.—but never ceases to have something to teach us.

The David Cooper quote that is at the top of this post pulls a very Cooper-esque parenthetical punch with a side eye second-hand quote of Heidegger about “the dreadful has already happened.” So you don’t have to scroll up, in the semiotexte Schizo-Culture issue, Cooper writes: "It is not true as the philosophers of pessimism say that ‘the dreadful has already happened’ (Heidegger) but it is true that we are haunted by the dreadful and it is true that there is no hope. There is only incessant, unrelenting struggle and that is the permanent creation of the hoped for…"

This assertion Cooper makes, written in 1978 and is quite likely a reaction to R.D. Laing's (a former peer and collaborator of Cooper) Heideggerarian conceptualization of alienation, which, unlike Hegel, Sartre, or Marx’s formulations, drops the centrality of labor and the cruel vicissitudes demanded by capitalist accumulation from the picture, replacing it with authenticity and Umheumlichkeit (novelty, the uncanny). Heidegger and Laing shared a similar line of reasoning in their work that Cooper was rejecting—which was the idea that feeling “at home” in the world, belonging, the alleviation of alienation, was not necessary to become whole. Both Laing and Heidegger’s work forwarded the idea that alienation is also often positive because it allows for the development of an authentic self and consciousness, a process that is allegedly numbed by being comfortable in the public world.

Cooper questions the point of this suffering for authenticity, and the individuation of it which in the process of atomization absolves capitalism and the conditions of labor, survival, and social reproduction of any blame. Cooper is not taking issue with Heidegger’s phenomenology of illness or being, but struggling against the depoliticization of illness and the philosophical imposition of 19th century temporality and techno-optimism onto his 1970s experience of the inefficacy of administering “mental illness treatment” that is focused on “the dreadful has already happened” event rather than the ongoing, protracted alienation mediated by extraction and abandonment. (And, by this point Cooper, himself at the time of writing having been recently pathologized and labeled mentally ill after many years as a psychiatrist, is also speaking from personal embodied experience, disowned by his peers and collaborators as a “crazy” hack and/or pervert. Some of the most well known anti-psychiatrists started as collaborators but were later always at war with one another over methods and the popular fame that some sought.)

Cooper is critical of the way authenticity as a conceptual frame controls who is put in the jail, prison, mental hospital or workhouse, and who is part of the world—he is calling on us to entrench our selves in the embodiment of illness to resist that politically. Cooper is drawing attention to the way the struggle for the authentic self upholds capitalism, and arguing that being in the world, seeking comfort and a sense of “at home”-ness is not numbing but liberatory:

To fill in the [crude outline of a ‘hypothesis’ for total liberation] and make it less crude depends on specific people and groups of people seizing consciousness not only of their oppression but of the specific modes of their repression in those particular institutions in which they live as functioning organisms and strive to keep alive as human beings. The living, palpating and now palpable solidarity that they invent is what brings the vision down to earth. …

We may say that anti- and non-psychiatric movements exist, but that no anti- or non-psychiatrists exist, any more than ‘schizophrenics’, ‘addicts’, ‘perverts’, or no mater what other psycho-diagnostic category.

[Note: Here, Cooper is not saying these categories are not “real,” he’s pointing to how the role of physician-expert is just as socially constructed and mutable as the rapid evolution of psychiatric diagnoses and categories, asking the reader to question any and all assertions of legitimacy and authenticity which uphold, perpetuate or produce oppression.]

What do exist are psychiatrists, psychologists, and all manner of psycho-technicians. The latter exist only precariously; when no roles remain for them to live, their very securizing identity is at stake…

There are two things to be done: firstly, the final extinguishing of capitalism and the entire mystifying ethos of private property; secondly, the social revolution against every form of repression, every violation of autonomy, every form of surveillance and every technique of mind-manipulation—the social revolution that must happen before, during and forever after the political revolution that will produce a classless society. If these things do not happen well within the limits of this century, within the life-span of most of us now living, our species will be doomed to rapid extinction.

— David Cooper, “The Invention of Non-Psychiatry” from semiotexte, Vol. III, No. 2, 1974 (emphasis original)

Of course none of this happened within Cooper’s lifetime, and we are now living in the doom he foretells in this essay. All the more reason to work towards political and social revolution in our own lifetimes. To do that we must listen to Mira and do now what people could not do for her before she died, refuse to turn away from the sick and dying.

My embodiment of illness involves a scale of both temporality and possibility that neither Heidegger, nor Laing, nor Cooper encountered. Yours does too. We are living in an era where these two competing theories of alienation, the good life, and the self are clashing on full display. My/our embodiment of illness is also subject to a level of diagnostic mediation that can make possibility feel more constrained and narrow in a forward looking way that Cooper and other contemporaries like Franco Basaglia of the Italian meta-psychiatry movement warned of decades ago. A lack of diagnosis or treatment now seems firm and sure, and can feel that way for decades until it suddenly doesn’t. My illness-time, the possibility of my “finitude” is different, my proximity to death is different and as knowledge of illness and disease changes, so does the living of being ill and diseased. So do the lessons we have to teach.

Please don’t turn away from the sick or even the dying. There are lessons we have to teach that some of you NEED about the brevity of life, about the importance of living fully, of not putting off your happiness until later.

And we need you.

—Mira Bellwether, 11:23 PM · Oct 30, 2022

I think there is a lot to gain from embracing the possibility of what we know we don’t know, to do that requires us to do good things like take Covid seriously (what is Covid’s long term impact on everyone: a known-unknown, but what we do know looks bad), and to believe people’s own expertise on their chronic illness (self-diagnosis is, after all, the first step in most every care encounter—you need to self-diagnose that you need to go to the doctor in the first place, unless you’re being brought there unconscious, against your will, or in an acute emergency, so a good first step is to question why you’re so scared of self-diagnosis).

Anyways, my alarm just went off, my dose is now at room temperature, and it’s time for me to start this new medication. I am hoping that this nearly 5k word stream of consciousness writing does not make people think I have more capacity than I do, but such are the anxieties of living with a chronic illness. I do not know if this drug will positively or negatively impact my capacity. I do not know if it will get me back to baseline, or how long adjusting to the side effects will be. I do not know if it will make me better, make me see again, or do nothing. I do not know what it will feel like, hopefully I don’t feel much of anything. All I know is that if it teaches me anything, I promise to teach it to you.

Thank you again for sticking with me this year. I wanted to pass along this update because I have so appreciated the ongoing solidarity and support while I have been without access to my medication. I do not know if I will have good news for you any time soon, or when I’ll have any news or all. But I just wanted to say thank you for being there with me. It has meant everything that you have not turned away.

I offer you the hope that I am willing to cultivate, not toxic-positivity, just the boring and simple truth. I hope this goes well and helps me. I hope that if you’re also trapped in a battle for your care, capacity, or autonomy up against the state, a large insurance company, your employer or whoever, that you keep pushing, fighting, and running those appeals out until you hit the final appeal. I hope you get all the care you deserve, and then some, and none of the so-called “care” you don’t want. Keep pushing.

As David Cooper writes in The Death of the Family: “Unless we are overly fond of…and are infatuated with the taste of our death we must spit it back in the face of the system that would cremate us…” If nothing else, make them look you in the eye as you are consigned to slow death by one thousand paper cuts.

Spit the taste of your own death back at that which seeks to sustain itself through your annihilation and let’s do our best to stay alive another week, one week at a time, together <3

Thank you for sticking with us, Bea. I’ve been disabled ( I’m in better shape now but recurrence is always a possibility), and I’m trying hard to stick with very elderly and dying people and not look away. It’s hard. Let us know how you are doing when you can.