Pierre Cardin: MAN

Trends, trads, and “ultras”; the three spirits of menswear (unceremoniously) laid to rest at the end of history...

This is the third and final essay in the three-part series reflecting on Pierre Cardin’s legacy in the year following his passing. HEALTH, TASTE, and now MAN have not precisely been a kind of eulogy. Instead, they are the rough sketches of a hypothesis as to the actual cultural impact of Pierre Cardin. As I will get into, it’s impossible to take Cardin himself at his word on this subject, though he frequently commented on what he wanted his history to become. The fashion press is—in my opinion—equally useless; when fashion legends die, all anyone ever has to say are empty, nice things. I have a few nice things to say, but I also want to tell you three very important stories which are often obscured by the fond ways we remember collections from years past. These are three cautionary tales, necessary warnings about how culture under capitalism leeches radicality out of everything it touches like a terrible, exuberant blight.

In the previous two essays, I have explored how Cardin used design to traverse class and cultural boundaries and how Cardin used clothing to imagine futures outside of the hegemonic structures and normative aesthetics of society. In the final essay, MAN, I examine how this boundary-crossing was received in real-time and how Cardin’s notions of dress as role-play and world-building helped to cement the mold for how many “transgressive” brands construct themselves today as signifiers that mimic a kind of radicality which is surface-level only—having been stripped of any real political coherence or antisocial qualities by necessity to reframe a “look” into a “product.”

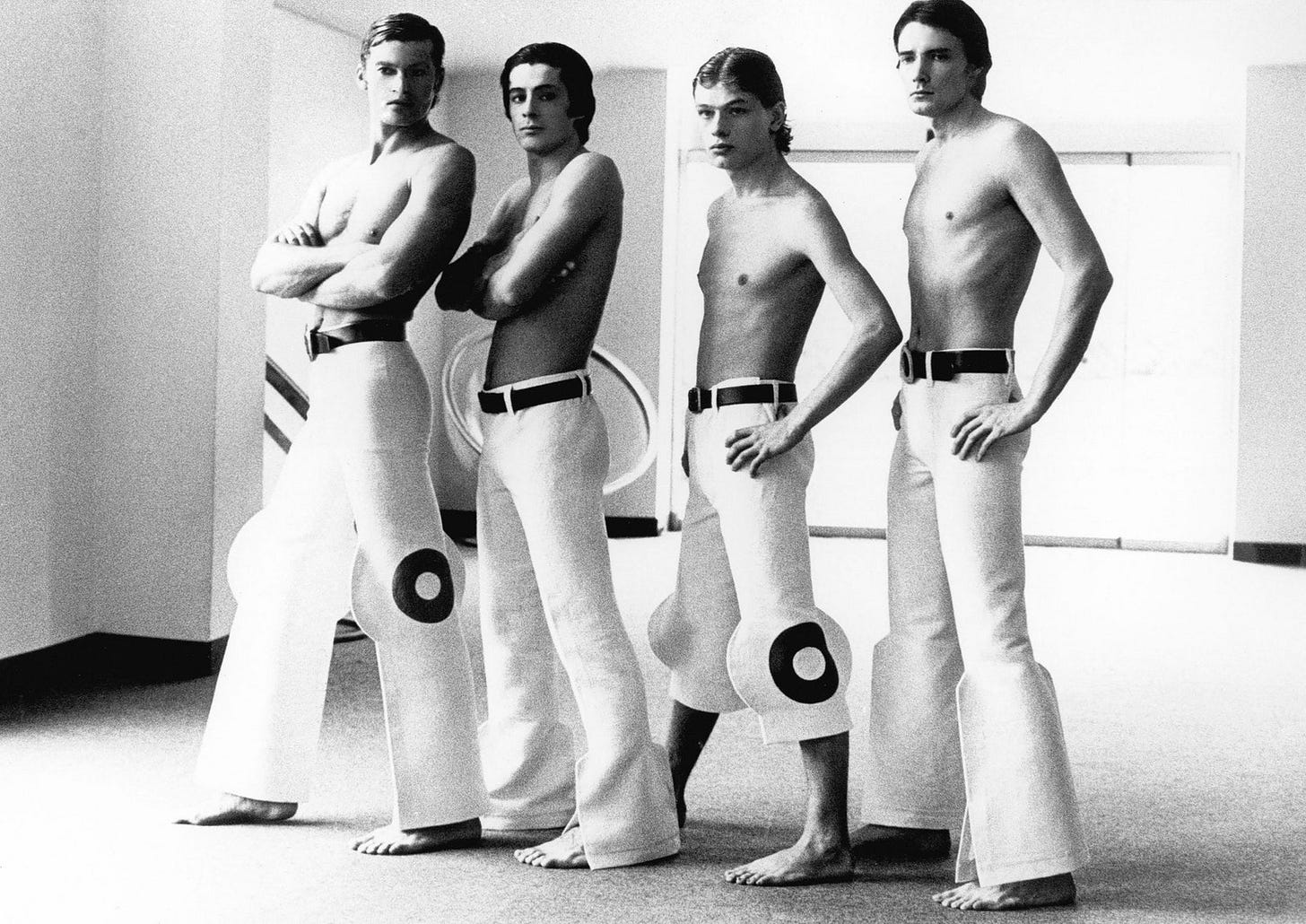

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Four masculine models stand shirtless in a blank and empty room wearing unique but matching white pants. Behind them is a white clear 60s “bubble chair” in all its chintzy glory. The pants are held up with black belts. From left to right, the first and the third pants have large black ‘O’s with circular panels extending from the silhouette of the pants. The second and fourth have rectangular panels extending from the pants. The first is a full-length pant with the ‘O’ above the knees, the second is a full-length pant with short square-ish rectangles at the ankles, the third is a calf-length pant, with the ‘O’s on the knees, the fourth is a full-length pant with long rectangles from the knee to the ankle and a large slit halfway up the shin down to the bottom. The models are barefoot. ]

“I wanted to create more than any old brands. I wanted a brand that would last for life.”

— Pierre Cardin

"Hear me!" cried the Ghost. "My time is nearly gone… I have sat invisible beside you, many and many a day… I am here tonight to warn you that you have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate… You will be haunted," resumed the Ghost, "by three spirits." … "Without their visits," said the Ghost, "you cannot hope to shun the path I tread."

— Charles Dickens, “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas.” From the collection of Pierpont Morgan. December 1843, Page 15.

I. The Three Spirits of Menswear

In this essay, I look at Pierre Cardin’s real impact, not as a designer, but as a tailor, as a fortune-teller, and then as a showman who built and destroyed representations of masculinity year after year for more than seven decades. First, I briefly examine the context in which Cardin’s work initially emerged, exploring the ways in which brands, aesthetics, fads, and trends become synched or locked to capitalist theories of worth and value. After which, are three ghost stories ("Without their visits," said the Ghost, "you cannot hope to shun the path I tread."); the ghost of trends-past (the struggle over masculinity in menswear), the ghost of trads-present (Cardin’s first menswear collection), and the ghost of “the” future (in which Cardin predicts his own death). We may yet learn from our own mistakes, it’s on us to embrace being haunted by fashion’s past.

Luxury fashion is a property regime like any other, with a unique and punishing product life cycle. It is thought that the breakneck pace and tendency for overproduction is justified as a necessary investment in the process of searching, seizing, and extracting “coolness.” Coolness is fleeting by nature, and part of the allure of fashion is that it is believed to be uniquely capable of keeping pace with “cool.” The institutions of fashion treat every “new-cool” as if it could become the next “lasting-cool”; the hype is part of the language of how the goods and services of fashion stay moving. It ultimately doesn’t matter if a brand is cool NOW if they can only capture the cool of a single temporal moment. Without lasting-coolness, there is no real market to develop, no customer relationship to maintain temporally.

I don’t think all brands must live forever—e.g., Cavalli was of a moment, and with that moment it should have been left, like with Von Dutch and American Apparel—but capitalism demands that all good things that produce good surplus-value must become as big and as profitable as possible to stay a good thing. To say “X brand has no staying power” under capitalism is a value judgment, but I do not mean it in that way. Under my imaginary of how we could do some kind of fashion-industry-without-capitalism, there is plenty—if not more—room for fads and short-lived aesthetics than how the industry is currently designed today.

But, not every brand needs to live forever. Not every brand should live forever. The myth of eternity is the metaphor capitalism uses as both carrot and stick.

[Image description: Color photograph, Cosmocorps collection. A group of models stands posed as if in mid-movement or dance on a low flight of stone steps. They are all wearing unique but matching outfits. The group is mostly young people, with one child visible crouching in an orange jumpsuit in the front. The colors of their outfits are monochromatic, with some in navy blue, some in orange, some in red, some in black, some in grey, some in white, and some in purple. The masculine models wear matching pants and moto jackets out of a wool-like material. The shoulders are strong with epaulets. The jackets are belted at the waist for most and are long-line, falling well below where a “normal” moto jacket would fall. Under their jackets are tight black t-shirts if the collar is open, otherwise, the collars of the masculine outfits are closed. They all wear matching black beetle boots. The feminine models are all wearing unique variations on the same dress, no two are the same combination of color and chest cut out. The dresses are the same material as the masculine outfits, a thick seemingly double-faced wool suiting. The dresses are sleeveless, with black turtlenecks and geometric tights underneath. Each dress is also belted at the waist with a belt that matches the dress, fastened with a shiny square chrome buckle. They wear black patent low heels.]

Let me be clear about what I mean by “fad.” A fad is an intense, short-lived, exaggerated, and disproportionately enthusiastic following of a practice, interest, ideology, or aesthetic—pathologized often as an “irrational craze.” I would contrast the short-term nature of fad with the more sustained medium of “trend” (but crucially, I would not position the two in opposition to each other, fad and trend are not binaries, though as I will discuss later on in this essay, they have often been portrayed as such).

A trend is a slower, more permanent change—a trend, most importantly, has a distinct direction; it’s going somewhere and will last once it arrives until the moment passes and a new trend rises in its place. At the most concentrated level, this is what separates a fad from a trend taxonomically. For a designer’s aesthetic to move beyond basic-fad into broader-trend, they must demonstrate not staying power but economic plasticity. Brands become houses when they can acquire the ability to not only mold the consumer’s look but be dynamically molded through a radical empathy for the desires of the imaginary future-consumer; a sense for the ghosts of trends-future. Conversely, the ghosts of trends-past tell us much about the political climate at the time they were dominant, and the limits of a brand to transcend the boundaries of its own relevancy wholly depend on its ability to evolve and iterate as political and social trends change.

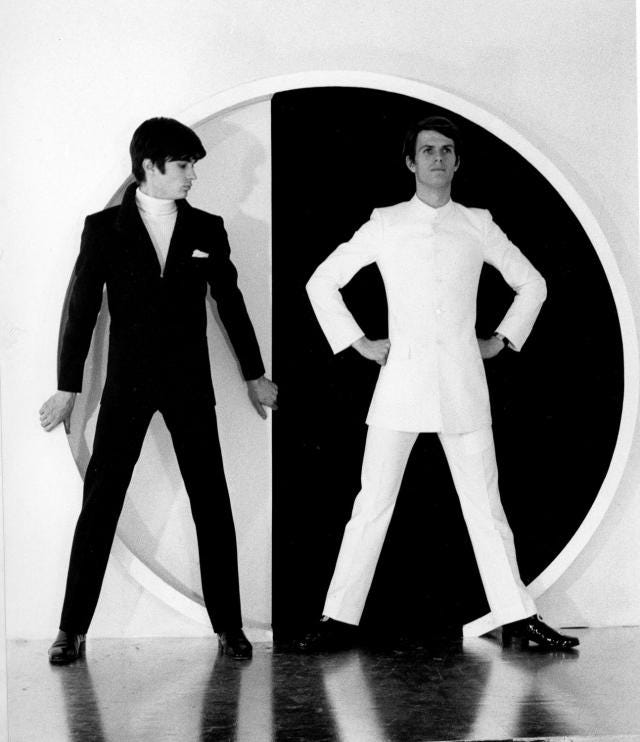

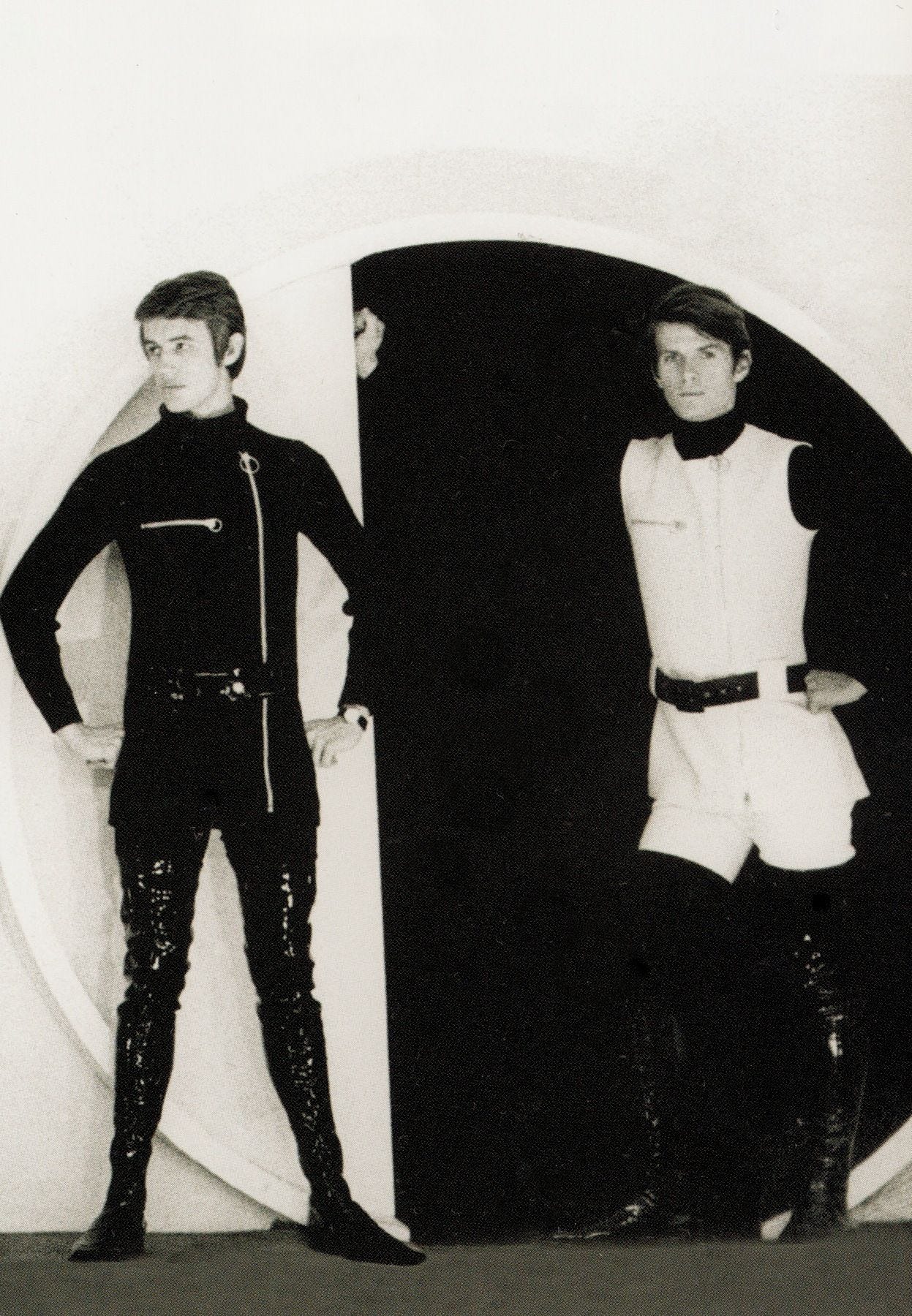

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Two models stand on a shiny black floor in front of a black and white circular doorway. Two-thirds of the doorway is a deep dark inky black. In front of that side of the doorway stands a masculine model in an all-white outfit. On the left side of the door, which is white like the wall, a model stands in an all-black masculine outfit. The model on the left in black is wearing a Cardin suit, which looks like a luxury cross between a workers jumpsuit and a Brooks Brothers suit. In the pocket is a bright white pocket square, and under the suit jacket is a delicate white knit mock neck top with no tie. The suit jacket is clearly also fastened with a zipper in place of the traditional buttons. The model on the right, in the all-white outfit, wears shiny black patent boots with O-Ring zipper closures up the middle and an all-white outfit which looks like a hybrid of a sailor’s uniform and a changshan or dagua, combining the long-line of the changshan/dagua style with the tightly nipped waist and pressed flat front pants of a military sailor.]

To put it plainly, if a brand under capitalism only seeks to dictate taste and style upon its wearer, without also extracting the taste and style of its own ecologies and relations—they are doing it wrong. A fashion brand imposes, but it also reflects. Imposing is engaging with a fad; reflecting is engaging with a trend.

Within what we would consider the “modern” iteration of the fashion industry, these two concepts were distinctly gendered at the outset. Womenswear was considered to be more fad-ish, changing often and encompassing a wide variety of styles dictating silhouettes, tastes, and styles upon its passive-objective consumer. Menswear was seen as more trend-driven, with the goal of reflecting the needs and drives projected upon the active-subjective consumer. In menswear, change was slow, norms of dress were not easily disrupted. There was not the same pressure for season over season innovation: following long-term trends was not only enough, but anything more than that was too much.

It is difficult to imagine menswear not being the market that it is today. Some of these debates we are about to revisit (especially those over ties) in our current context sound not just absurd but out of touch with reality. Did people really think that the world would end if men stopped wearing workplace uniforms? Yes, yes they did, and it was silly—but it also decidedly wasn’t very funny, and was pretty sad and violent too. This debate, over the nature and purpose of mens fashion, is a brutal and overlooked narrative in the history of fashion. We owe it to Cardin to think more deeply about what a brand can do, who it helps and hurts politically, culturally, socially, and why. Why does gendered fashion matter, who does it matter to? Why did people claim Cardin to be a gender-less fashion revolutionary? These are just some of the questions that make up Cardin’s legacy which we rarely revisit. The culture war over menswear is an important and underexamined history that we would benefit from reckoning with.

I wanted to talk about this in the context of Pierre Cardin because he claimed credit as not just the first unisex designer, but as the first true menswear fashion designer in all of history. Nothing that came before him was fashion (in his opinion)—Cardin claimed his brand and aesthetic would wax and wane, yet ultimately prove eternal. He mythologized himself in real-time, invented, stoked, and conquered every controversy in the press, and constantly thought of the Future not as a temporal moment far ahead of us in time, but as a physical object—a category of objects—made to be sold, and appropriated by the owner to construct a readily readable social and cultural identity.

Cardin’s ultimate legacy may not be the creation of a totally timeless forever brand for the whole family, a full lifestyle, as he famously wished it to be. It’s arguable that, instead, Cardin should be remembered for ushering in a new era of apolitical unisex fashion, which offered itself up as a sacrificial strawman to a conservative culture obsessed with defining new justifications for the siloing of masculinity and masculine aesthetics into distinct and stable categories.

The menswear market has certainly come so far from the dynamic present when Cardin began his journey as the “first menswear fashion designer” yet this revolution of mens fashion was by no means revolutionary, it is simply a more complex product driven by an even more complex matrix of profit relations. But to understand just how far the construction of gendered fashion has come and how much it has changed as capitalism has changed the way we wear and consume clothes, it is crucial to understand the political ecology of dress which Cardin “allegedly” so-unceremoniously disrupted in the early 60s whether he “invented” menswear or not.

[Image description: Black and white photograph. A group of mostly masculine models stands in front of the same circular door as the previous photograph, with the same model in the all-white suit standing in the deep black portion of the doorway. To his left are four adults and one child. From right to left, they are wearing the following unique but matching outfits. The first to the right of the man in the all-white suit is a feminine model in a shiny short cut out dress with stockingless legs. The dress is collared with a band of fabric across the chest and across the stomach connected by a central column of fabric. The next figure is in a masculine outfit, a single one-piece, which looks to be made of leather and suede has a large central zipper with an O Ring zipper pull. The jumpsuit looks like a mix between a worker’s jumpsuit and a motorcycle jacket/outfit. The next figure is in a masculine outfit, wearing leather pants and a sleeveless shiny chainmail shirt over a black turtleneck. The chainmail looks like a disco ball more than it looks like chain. The next model is a child in a similar but unique black leather jumpsuit to the other masculine outfit for the adult model. Th next and final figure wears a more formal jumpsuit made from a grey boucle suiting with thick black trim around the collar and central zipper with a decorative geometric pattern. All except for the model in the all-white outfit have both hands on their hips, the model in the all-white outfit has their left hand on their hip while they stand contrapposto balancing their weight on their right hand which rests on the center of the circular doorway.]

To me, this is Cardin’s most significant achievement, and I was disappointed that it was not more considered in the shallow coverage of his death. I felt I owed it to him to spend time thinking and talking about it, and what I found were three stories—warnings. These tales of menswear and Cardin’s life paint a dark picture, a warning of what futures may still come to pass and a reminder that for all that the fashion industry focuses on the birth of fashion—season after season, collection after collection, creative director after creative director—it rarely ever stops to think about all the death which comes with fashion. We rarely stop to think of all the waste, all the harm, and pain, and violence of our political-economic system and the power that fashion, and more importantly gendered fashion, holds in our present.

II. The Ghost of Trends-Past

Pierre Cardin got his start as a menswear tailor (circa the early 1930s) before moving into womenswear in 1945 as a designer for the early fashion house Paquin, and, later, for the one and only, Elsa Schiaparelli. As Cardin tells the story, he demonstrated such a promising personal design aesthetic that within two years of formally working as a womenswear designer, he became the head of Christian Dior's tailleure—which was, by all accounts, a pretty huge-fucking-deal at the time. After a few years of toiling under someone else’s creative direction, in 1950, Cardin went on to found his eponymous brand, “Pierre Cardin.” Cardin rose to prominence quite quickly as a solo act—he was already renowned for his meticulous attention to detail. Most fashion critics had considered Cardin a hot-one-to-watch on the womenswear scene for several years before he founded his line, which he described as only confirming the rarity of talent he already knew himself to possess.

Cardin’s propensity to self-mythologize and romanticize the portrayal of his own genius was a foundational demonstration of the “creative director” model of fashion-brand formation. In this model, the brand narrative and corresponding suite of products are constructed around a central theme of individualism, of personality turned to gold through alchemy— “creativity in its purest form,” crudely commodified. Consuming fashion has often, under the creative director model, taken on a kind of cultural transubstantiation like fashion’s equivalent to the Eucharist—but rather than imbibing the body and blood of Christ towards theoretical religious purity, we consume the genius of the creative director, wearing their garments on our bodies, carrying their bags in our hands, their shoes on our feet, their eau on our dressers.

In the mid-1950s, as Cardin was launching his namesake brand, women had fashion, and men had tailoring—two very distinct and different industries with utterly different product life cycles, design philosophies, and approaches to aesthetics. In the 50s and decades immediately prior, menswear was seen as a sort of timeless; the possibility of decadent and exploratory modes of dress for men had been written out of the collective imaginary. The dandy was dead. The industry of men’s clothing as a whole united around the narrative that men’s clothes were so entirely different from women’s clothes that the menswear industry would never in any possible future catch up to the pace of innovation of womenswear.

There was little room to push boundaries and explore dress at a mass scale until the early 50s when Cardin hits the market, and his claim to first-influence in the arena of the avant moderne was foundational to the mythos of his branding. Beyond his interventions in womenswear, which were numerous, Pierre Cardin is widely credited with “inventing” the contemporary menswear market, or la mode masculine, and also with developing, designing, marketing, and selling some of the first “unisex” luxury fashions starting with his groundbreaking Cosmocorps collection.

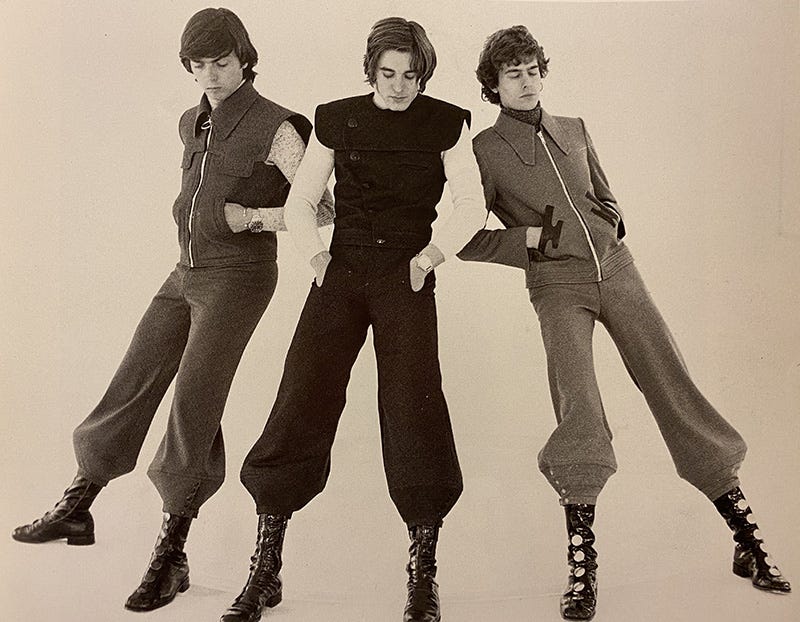

[Image description: Black and white photograph, with tan overtone. Three figures in matching but unique masculine two pieced coordinated outfits. Each of the models stands with their legs wide, showing off the sculptural details of their unique but matching pants. Each pant has a kind of funnel leg at the ankle, which creates a structured and tapered balloon effect, which looks a little like a futuristic interpretation of riding breeches or upside-down, slimmed gallifet trousers. They each wear shiny high boots that the high-waisted, sculptural pants tuck into. The figures all fan out as if their heads rest on one pillow, while they lie on the ground, heads touching looking up at the sky or clouds, except all the figures are standing, there appears to be transitory or no gravity, though their hair is not floating and they otherwise appear to be under normal “earth gravity” a technique used often by Cardin in his lookbooks. The figure on the left wears a darker grey outfit with a sleeveless top that has moto-inspiration, though is rendered in chunky suiting, under the top is a grey marled long-sleeve. The center figure appears to be in a light black, dark grey, or navy blue outfit. This top is also sleeveless, but with padded shoulder pieces, under is a white long-sleeve. The third figure is wearing lighter grey, the top is long-sleeved and zips up looking very much like a workers or chore jacket with an exaggerated collar rendered in thick wool suiting.]

As with most of Cardin’s self-aggrandizing claims, this assertion that he “created” or “invented” unisex and all edgy men’s clothing should always be taken as hyperbolic—e.g., Cardin on the mere existence of menswear designers before him: “There were none. When I presented my line, there were only the eccentricities of youth.” (He’s not wrong in a way, but he’s not right either.)

Cardin’s self-professed achievements are less facts of the historical record and more the remnant husks of one of the most significant market experiments of the mid-twentieth century: luxury lifestyle branding. However, Cardin’s significant innovations in the male silhouette were not necessarily universally welcome. Cardin’s work in menswear-inspired just as much outrage as it did exuberant devotees. Fashion has long been a battleground of normality and the boundaries of what society at large deems acceptable and welcome in the community, with designers and creative directors seen as deity-like mediators of this complex dynamic of collective consensual normalization.

Nowhere is this more true than in the arena of menswear. As diverse styles in womenswear became more available to the mass market via the explosion of commercial licensing, overcoming the limits of previously tedious production methods, the menswear market stubbornly held on to “old-world values of dress” in a firmly conservative and revanchist way, not only defying growth but actively seeking de-growth as an industry—quite the opposite of the current menswear market. After centuries of reflection and cohesion between gendered garment production, the two industries had not only separated but become each other’s inverse. A story was told which resituated this separation between menswear and womenswear as always having been true, but at Cardin’s own calculation, it was at best, less than 100 years old as a trend.

By the early 1970s, the resistance to change in menswear had become pathologized as the field of battle in the war to retain a kind of heterosexual-default masculine cultural uniform; the “thin blue line” standing between thousands of standard 4” navy blue ties and the rise of a new era of decadent (degenerate, illegible) dandy-ism. A world filled with Cardin suits and fur for men was terrifying, possibly the first sign that it was the end of history and civilization. Many deemed that that was some sort of sign of a larger degeneration within the culture, a sign that perhaps the aesthetics of the 1970s were heralding the end of history.

[Image description: Color photograph. Five models in front of a white seamless. All models are wearing unique but matching masculine outfits. From left to right: The first model faces forward straight into the camera, yet looks off frame. He is wearing black leather pants and a tan short collared long-line coat which comes down to the mid-thigh. The coat is structured shoulders and a small pocket on the right breast. Under is a black turtleneck that just barely shows over the mock-neck. The next four figures stand with their sides to the camera and their hands flat on their hips with precision. It looks like they are in waiting to take the first figure’s pose next, like synchronized swimmers on land. The first side-facing figure is in a black outfit with dropped pants and tall white socks. The second side-facing figure is wearing a rust-brown outfit, with cropped pants and tall black leather boots. The third side-facing figure is wearing a hunter-green outfit with cropped pants and high patterned socks. The final figure is in tan, with flared cropped pants and tall black boots.]

This conservative approach to understanding menswear as being constantly at a point of crisis and in need of protection became the dominant narrative within the industry press. The anxiety of critics was that if aesthetics of dress shifted, the behavioral dynamics between men carefully coded into society via readily recognizable class boundaries identified by various “masculine uniforms” would destabilize as a result. This hysterical preoccupation with an imagined “fashion choices to degenerate-gender relations pipeline” fueled a wave of forced aesthetic normalization in the 1980s that would wipe out the Cardin-suit among many other silhouettes in menswear we are only now regaining access to at a broader market scale.

Certain sectors of the menswear market were heavily invested in maintaining hegemonic control over what was in fashion. As the handmaidens to power that they are, critics were heavily biased in favor of maintaining strict borders and boundaries around the heterosexual male uniform. Nothing sells better than moral panic fashion outrage.

Critics often accused Cardin of forcing “feminization” on the “elite institution” of menswear, outraging fashion critics and sales-floor commentators with such deliberate disregard of the visual norms of the masculine workplace uniform. Others went further, claiming that Cardin’s designs would poison the well, undermine the dignity of male dress, or too aggressively disrupt familial relations. Thus Cardin’s simple intervention of, ‘maybe everyone could just wear whatever the fuck they want, as long as they look cool doing it,’ starts to take on the appearance of radicality or boundary-pushing akin to revolutionary political thought in the public imaginary despite not being a particularly radical, inclusive, or norm-disrupting perspective. Regardless, resistance to Cardin’s menswear shows began to incite a chorus of conservative commentators who decried the new dandyism, leading to further revanchist calls to return to “proper” male dress.

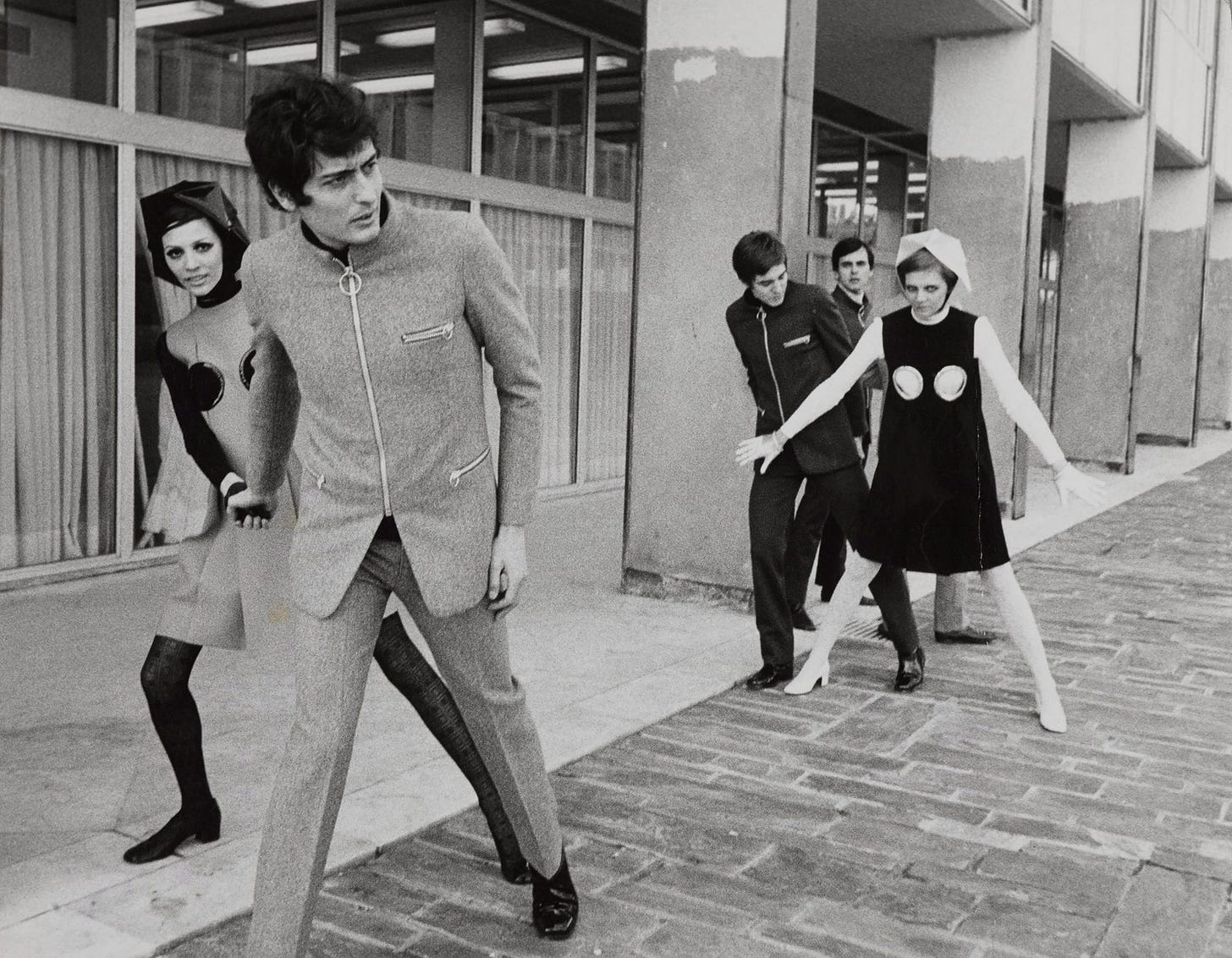

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Two groups of models walk and frolic in a public plaza or outdoor area of a large building. The first two models, closest to the camera are wearing outfits made of grey suiting. The masculine figure is in a two-piece Cardin suit, and the feminine figure wears a dress with cutouts over the breasts. On her head is an unusual cloth hat. Under the dress is a black turtle-neck long sleeve, and she wears black tights. Behind them in a second group, being held back by the feminine model who stands with her ankles spread wide and her arms out, as if trying to hold back a rushing crowd wears a black and white version of the dress the first feminine model wears. The two masculine figures she holds back are wearing black Cardin suits, the first with a black turtleneck under and the second with a white one.]

Let’s do a quick close read to demonstrate just how this pervasive conservative bias was within men’s fashion commentary is by looking at one of the most archetypal examples of this argument that men’s fashion is in a crisis over the taste and quality of masculinity. The New York Times fashion critics had, for many years, already been wondering aloud if the runway aesthetics of the 60s and 70s really reflected the conservative values of the New York Times readership, who were assumed to be the demographic that the entire industry of fashion revolved around. In 1977, designer John Weitz was asked by fashion critic, Elaine Louie, to comment on the growing (radical) trend of ties narrower than 4” for an article she was preparing called What Insiders Say About Men’s Fashion. Rather than a simple exploration of fall trends, Louie delves into some quite deep and existential questions like; was men’s fashion still serving its purpose? Or, had the industry gone astray, steering off-course, too dangerously close to women’s fashions, leaving the average consumer stranded, confused, and insecure in its wake?

Louie: “Unlike women’s fashion, menswear doesn't change silhouettes overnight. It moves slowly, but firmly, to ‘update’ fashion … The British / American / Ivy League look is for the 95% of American men who don’t want people to faint in horror or scream with delight as they enter the room. (They do want their colleagues to mutter behind their backs, ‘doesn’t John look smart these days?) But there are those 5% who do want to make an entrance. They too have their choices — from a highly sophisticated European look to an unmistakable, oilman machismo … The 70’s is a neater, trimmer decade than the 60’s. Everyone has cut his hair. (Ralph Lauren’s 8 year-old son asked if he could wear a tie … ) But this so-called conservatism also heralds the return of good taste and quality.”

Weitz then explains the true challenge is to find equilibrium between the principles of fashion and the principle goal of menswear, which is to find comfort in fitting in. Weitz: “men don’t get desperate because their tie isn’t exactly correct. They do feel badly if they’re unsuitably dressed. If everybody’s in navy, and one man’s in pink, that man feels bad. 30% of all my ties that are sold are dark blue. Is that creative? Men are self-protective.” Weitz felt that some designers (like Cardin) veered a little too far from the intended principle goal of men’s fashion as a social reproductive tool of masculine safety. The goal of the menswear designer was to provide men with safety through their uniforms, through their collective standardization, through the physical reproduction of hegemony. This projection of aesthetic normalcy = masculine safety net was less related to any actual reality and more related to the differences in opinion between what Weitz and Cardin each thought a man should look like and what each designer’s customer wanted to look like.

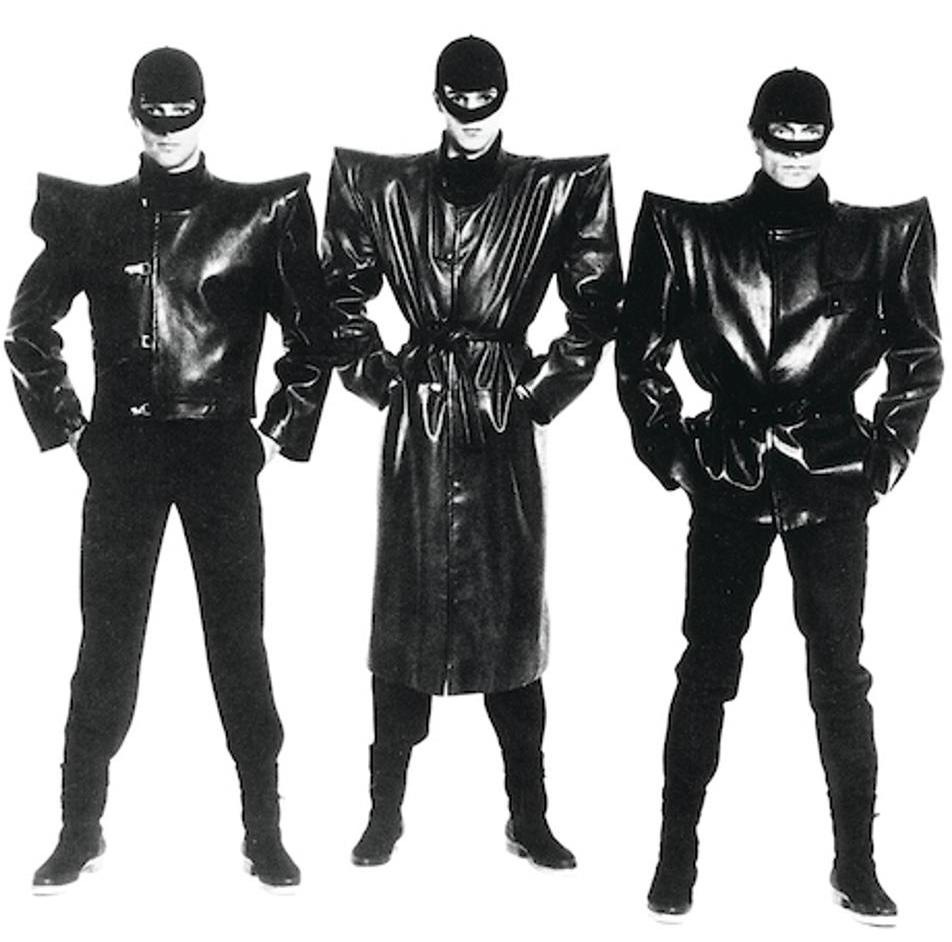

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Three models stand squarely facing the camera in unique but matching outfits made of black shiny material, likely leather, and patent leather. All three wear ominous black half-hoods, obscuring the top half of their faces. They each wear different outerwear that has the same interesting and striking shoulder design, which is exaggerated and large, with shoulder pads. Instead of just being large at the shoulder though, these curve upwards like little devil horns. Standing shoulder to shoulder, each jacket almost barely touches the next. The model in the middle is wearing a long-line version, the two outer figures are wearing cropped versions. On the bottom, they wear black leather tight pants and black patent boots with bright white souls, which are difficult to see and blown out by the high contrast in the image.]

By leaps and bounds, Weitz, a designer, turned-historian, and later-historical-novelist, was a much different designer than Cardin; best known for looks that harkened back to a “literary” aesthetic of the British upper-class. Weitz was a modern traditionalist—he, like all designers at the time, fully embraced the new wonders of synthetic fabrics. Conservatives like Weitz felt that being a cutting-edge brand was not about aesthetics or edginess but about technology. Weitz also had a licensing empire and had, since 1950. Weitz was, in his opinion, thoroughly modern—to the very conservative core of high modernism, which can often be so destructive to perceived threats to norms. By way of example, Weitz in the same article by Louie on why the modern menswear designer simply must work with new tech fabrics and synthetics: “I design in blends for two reasons. There are no more servants, and wives don't want to iron.”

The design problem Weitz seeks to solve is: how to keep a man looking like he still has servants or a wife who likes to iron, even if society has “degenerated” to the point that a man simply no longer has reasonable access to servants and a wife who likes to iron. Modernity, therefore, becomes the embrace of the technology that restores the norm, not the revolutionization of the meaning and look of the norm.

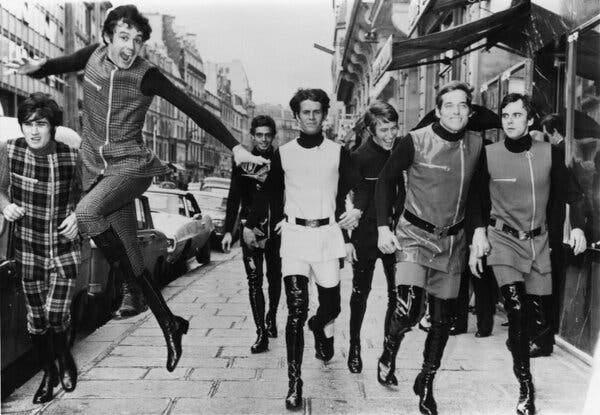

[Image description: Black and white photograph. A group of masculine models in unique but matching outfits run towards the camera in a group down a non-descript French side street. They are joyful and running fairly hard, not in the sort of light way you see in 1990s advertising, where models are almost playing at being active, these models are really running, they look very young and they are all very lanky in matching thigh-high patent boots and sleeveless longline tunics with matching pants. Some are in solid color grey, white or black ones, some wear leather versions of the outfit, and the two on the left are wearing plaid versions of the outfit. The figure closest to the camera is caught mid-jump, looking at the camera with a wide-open grin arms in the air like he’s flying.]

Louie, the critic, concurs and continues: “Men don't like to iron shirts either. Even Cotton Inc., the private company owned by America's cotton growers, recognizes this fact and is promoting 60% cotton, 40% synthetic blends, which offer some breathability and lots of easy care. DuPont's director of menswear, Gomer Ward, sees textured wovens becoming even more popular for slacks, suitings and outerwear and high‐priced Qiana holding its own in the purely synthetic market — but the day of the cheap nylon shirt is over. If the blended shirts keep the traveling businessman neat and tidy, the pure cotton ones will keep Chinese laundries alive.” Truly, it’s hard to underemphasize how much absurd racist bullshit, consistently preoccupied with sowing fear about queerness and the destruction of gender norms, passes as fashion criticism.

Another designer quoted in the piece, Monte Corner, who was the CEO of a brand now lost to history called “Phoenix Clothes,” states: “Our macho look is for the big, broad, athletic guy who's conscious of the opposite sex.” Weitz and Corner, like many of the more conservative menswear designers of the time like Bill Blass, Ralph Lauren, Stanley Blacker, Eric Ross, Saint Laurent, and Larry Kane, preferred a men’s silhouette that brought the “best of the 30s, the 40s, and the 50s—all updated, and subdued….” The dandy is being foretold dead; Louie quotes Lauren as saying, “hokey doesn’t sell,” and Saint Laurent’s Michel Zelnick as saying, “the American man would rather spend his money on his wife and children than on himself.” The Macho Man™ was declared in, the theatricality of men’s fashion was better kept to the stage of the fashion show and the rest can wear Clothes for Men™.

III. The Ghost of Trads-Present

Cardin, who again gets his start as a tailor, not a fashion designer, begins to emerge as dominant within the global space of womenswear. He soars past his ten-year test, wielding significant power over the aesthetic trend of the fashion world. By spring - summer 1960, Cardin’s name became synonymous with a certain Parisian chicness—his futuristic fashions were ever more widely praised and loved with each further push towards the avant-garde. At this point, the story goes that Cardin returns to his first love—designing clothes for men—and begins to incorporate male models and menswear into his previously all womenswear presentations.

[Image description: page 76 of The New York Times on October 26, 1967. Article titled: “It’s a Quarter Past Cardin,” article is accompanied by an illustration of two gloves and two watches with half their face missing. Link to read full article on NYT archive.]

Of his first menswear show, reviewed by the New York Times in an article in the March 15, 1960 edition of the paper called Cardin Designs Bright Plumage For the Males, an anonymous fashion critic writes:

A bearded young Frenchman, who has chosen law as his career, sparked a revolution this week. The place, however, was not Algiers but Paris’ Crillion Hotel, and the young man was not Pierre Lagaillarde but one of a handful of students whom Pierre Cardin, the widely known designer of womens fashions, had chosen to model his new collection of ready-to-wear clothes for men…

Pierre Lagaillarde is a strange person to name as a revolutionary if you’re not a pro-colonial white supremacist, and I would also happily die on a hill arguing that any comparison to him is not a compliment but an insult regardless of your politics. The “revolutionary” that this New York Times fashion critic is cheekily referring to is none other than the French law-student leader of a 1958 right-wing partisan coup d’état which successfully returned Charles de Gaulle to power, helping to keep Algeria under French colonial rule for another four brutal and bloody years of needless suffering. Lagaillarde, who was a lawyer and reserve-paratrooper in Bilda, Algiers, had become minorly famous in the media as one of the faces of the insurrection during the “week of the barricades” in January 1960. Lagaillarde was what was called an “ultra” or “colon-extremist,,” which was a group of European pro-colonial diehards who organized to support the continuation of French colonial interests in Africa. This is just a casual, contextual inside joke about white supremacy being kind of relative to chicness in the New York Times Style Section. History, inevitably, repeats itself.

In opposition to people like Lagaillarde and his merry band of fellow “ultras” were groups like the French Communist Party, the French Section of the Worker’s International, and the Radical-Socialist Party, who were organizing in solidarity with Algerian independence. This is crucial context for understanding the nuance of the New York Times fashion critic and from which political perspective this criticism has been born. To celebrate Lagaillarde as such an insider joke in the article, was also to align the masculine uniform with the pro-colon movement. So what then does the comment that Cardin is acting like such a “revolutionary” actually convey to us if we are considering it from the position of the 1960 New York Times style page reader? It tells us more about who the consumer of ‘mens fashion’ at the time might be, who the intended audience is, and it definitely tells us who they think should be in power and why.

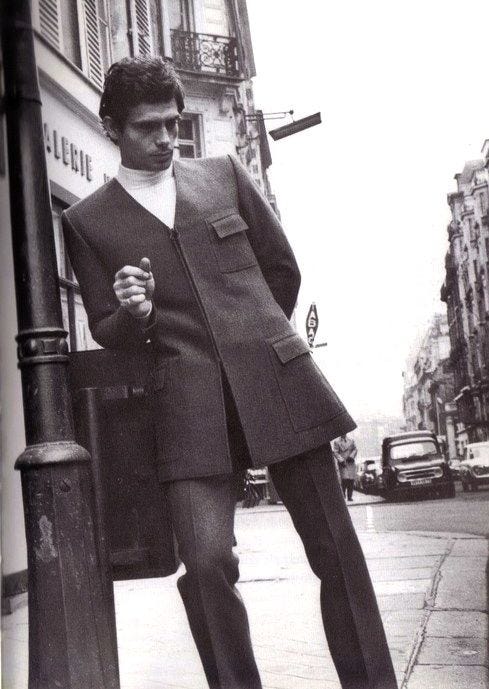

[Image description: Black and white photograph. A single model in a masculine Cardin suit stands on Paris street. He leans on a light post, hand clasped and looking down. This suit is v-neck with no collar, at the bottom hem, opposite the neckline is a complimentary slit in the jacket, which flares out dramatically at the waist. The pants are neat and tailored suit pants, though tighter and with starched creases in the center. Under the jacket is a white turtleneck made out of a ribbed knit.]

As the article continues, it becomes pretty clear just how conservative this fashion-commentator-elite truly is and how frustrated Cardin’s work makes them despite being clearly more than a little bit captivated by the looks. For this reason alone, I believe that fashion history needs to reestablish Cardin as the king of menswear. Few things seem to boil conservative blood more than thin young men, looking so good in something that can’t even be identified as a standard garment. Cardin’s work is often called a Cardin suit in an attempt to reassert control over his abject refusal to design suits (though he was a daily wearer of them). The non-suit, also a non-separate, was really just a jumpsuit. Cardin was appropriating the aesthetic of the working class, of the lumpen-uniform, of the young socialist-realist factory boy with long eyelashes in a grey pinstriped onesie but refined for the upper class.

It was pretty unusual compared with what a suit was supposed to look like in 1960, and it looked really good on the young models that Cardin chose to walk in the show. Even the conservative fashion critic, who clearly knows nothing about a sense of true style, is overwhelmingly wooed by Cardin’s strange suit. He wouldn’t wear it; he kind of hates it, but he gets it. He really tries to justify it for himself, and he historicizes it:

We may live to see the day when husbands will say to their wives: “What do you think of my new Cardin suit?” … In his collection for men, however, Cardin had in mind not so much France’s immortals as her youth. In style, his new fashions modeled before an audience containing many students, fall somewhere between the English and the Italian. … Some Cardin innovations include the unpadded Cardin shoulders that slope down at a steep grade, collarless jackets reminiscent of those worn by Russian officers, British clergymen or bellhops; buttonless sleeves, and a single slit in the back of the jackets…

The anon-critic is dead-serious about his fashion-phrenology, offering a glimpse at the intricate ways in which the inspiration of men’s fashion has always been tied to themes of the workplace and uniform, reinforcing the ontological connection between being well-dressed and being well-employed as if these two qualities are always found paired in nature.

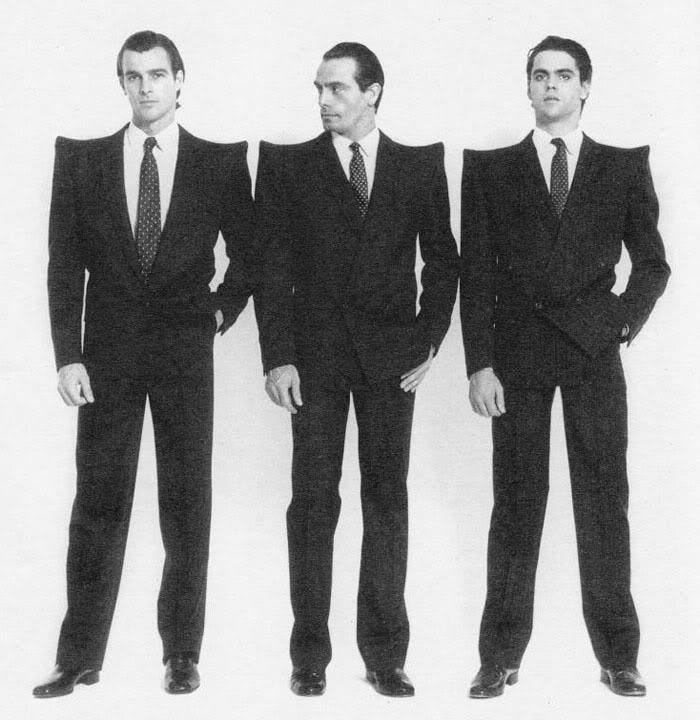

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Three models stand looking like near-copies of each other, with slicked-back dark hair, and wearing matching black suits and black patent dress shoes. The suits are passable as “normal” suits in all qualities except for the shoulder pads. Which are not just exaggerated but upturned into curves like small devil horns. The models accentuate the strangeness of this image by standing in similar positions and looking vaguely shifty in their facial expressions. Each has their left hand on their hip and their right hand hanging down by the side. Their legs are in mirrored poses as well, with the center model standing straight facing the camera with ankles narrow and straight, and the two outer figures standing with wider legs as if they, “the edges,” are more flared out.]

The anon-critic continues, contemplating if Cardin’s designs and his new aesthetic for men will actually be adopted in the ordinary world of menswear, not relegated to the narrow constituency of the few remaining and shunned dandies. The anon-critic can’t imagine a world filled with “men” in these suits, but they also, terrifyingly, absolutely can. Panicking, the critic, as critics do, polls the crowd. Seeking to reinforce his worldview. Searching for confirmation bias, asking all of the handsome young law students turned male models what they thought of this new mode masculine as if the opinions of the models actually matter. As if the magic of Cardin’s social reproductive flair hadn’t already fully worked:

However, most of the comments revealed that there are no more conservative people than the young—at least in matters of dress. This indicates that some of Cardin’s more extravagant flights of fancy, such as tight knickerbockers, foulard shirts, and huge leather belts, will not remain in the line for long.

The anonymous reporter’s prediction, it turns out, did not pan out—any half-assed analysis of the past seventy years of menswear so clearly demonstrates that this New York Times fashion critic had no fucking clue what they were talking about. Cardin had absolutely hit on a trend in menswear that was about to explode in the decade following his first Paris menswear show. Cardin was not founding a trend but riding it. Moreover, what the critic failed to realize is that fashion’s own parasitic relationship to avant and counter-culture would only continue to put it at odds with conservative aesthetics, never returning to tradition but instead “leaning in” to perpetuate the myth that men’s fashion too was somehow an inverse or anti-revanchist liberal regime of workplace rebels. When radicality is commodified, when rebellion becomes abstracted as being always relational to clothing, it’s important to ask who’s radicality, and which rebellion, and over what before proceeding.

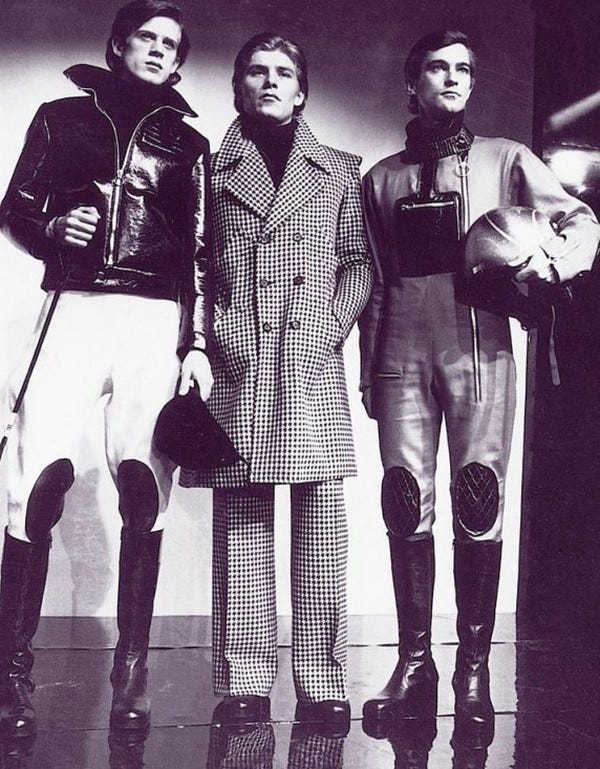

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Three models stand wearing what looks like intricate pseudo-formal riding wear. The center figure is in a bold optic-plaid coordinated suit that consists of suit pants, and a longline men’s double-breasted coat rendered in matching fabric. The collar is popped and exaggerated, framing the classic black turtleneck the model wears. The model to the left wears a more equestrian outfit with jodhpur-like pants tucked into tall black boots. He wears a cropped patent coat that looks like a leather puffer version of a cropped work coat, with a stiff collar and square silhouette. The figure on the right looks like a space-equestrian. Wearing a jodhpur-jumpsuit out of light or grey leather, with black trim and details. On the chest is a sewn-in black pouch, like a backpack pocket on the front of the garment, which has a large and chunky knit collar. This model carries a helmet and is looking off into the distance out of frame as if waiting for something.]

IV. The Ghost of “the” Future

Pierre Cardin was a designer whose aesthetic from the mid-40s forward was always intended to be, feel, and look not only modern but futuristic. Cardin’s own definition of what futuristic clothing meant was clothing that quite literally had the feeling and the look of Futurism, an art historical movement from the early 20th century which developed in Italy and later Russia, translated through the lens of new-French cosmopolitan internationalism. It just so happens that this same look, which many would today term “retro-futurist” or “space age,” was incredibly cohesive with the philosophy of the future fueling state-scale projects like the American space program and fulfilling the theory of beauty portrayed in American cultural interpretations of the new mid-Century Futurist commercial landscape. It was also a fundamentally right-wing pro-capitalist study of beauty, producing an ideology that would come to behaviorally define the entire fashion industry through the latter half of the century into our current moment.

Futurism embraced themes of dynamism, speed, technology, youth, and violence, often centered through representations of consumer objects of the state or corporation; feats of modern commercial engineering like automobiles, trains, and later airplanes. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, author of the Manifesto of Futurism (1909) explained the movement as such: “We say that the world's magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed... A new beauty has been added to the splendor of the world - the beauty of speed.”

[Image description: Black and white photograph. The masculine model stands in the center of the frame looking at the camera on Paris street. He wears a full leather outfit, inspired by a motorcycle outfit, but distinctively-not a motorcycle outfit. His boots are dark, worn suede, suggesting this is a candid photograph and the boots are the model’s own or he is a man who wears Cardin head to toe, caught on the street. Likely the dust is simply the dust of gravel from the nearby Jardin des Tuileries, known for its classic and dusty light-khaki gravel paths, which was a location that Cardin frequently liked to shoot his models in, as they walked, “acting naturally,” in the perfectly manicured quintessential French park. The pants are black leather, tight, so tight that they need buttoned flaps at each ankle to allow the foot to pass through, the pants tuck neatly into the dusty boots. The moto-jacket on the top is dramatic and highly structured, with a thick collar that contrasts playfully with the tied waist. The shoulders are difficult to describe, they are geometric and large, and look more like a digital render than a garment. It’s a kind of speaker shape, like a series of nested conical objects that fit together with a small space in between.]

It is understandable why this authoritarian and violent ideology about the meaning and purpose of beauty would be inspiring to a young Cardin. Futurism embodied a violent, warlike purpose of endless progressive forward consumption, e.g., Marinetti: “We will glorify war-the world's only hygiene, militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for...” In the fashion world of the mid-Century, this ideology also rang true as licensing became the beast which would consume the industry from within like malignant cancer, e.g., Marinetti: “Let us leave good sense behind like a hideous husk and let us hurl ourselves, like fruit spiced with pride, into the immense mouth and breast of the world! Let us feed the unknown, not from despair, but simply to enrich the unfathomable reservoirs of the Absurd!”

The ideology of Futurism began to infect the market logic of the fashion industry, driving the commitment to constant acceleration in both production speeds and in the inflation of prices, e.g., Marinetti: “It is therefore necessary to prepare the imminent and inevitable identification of man with the motor, facilitating and perfecting an incessant exchange of intuition, rhythm, instinct, and metallic discipline, quite utterly unknown to the majority of humanity and only divined by the most lucid mind.” Futurism and its rapture for the speed of capitalist reproduction is the driving ideological force behind fashion’s retail calendar. And as this trend picks up and begins to gain momentum around 1940, Cardin himself also begins to draw heavy aesthetic and political inspiration from the same movement, seemingly arriving, fully formed at a new-now-coolness at precisely the moment the fashion industry was wondering if it was possible to visually embody the new “future-mood” of the fashion industry within the products of fashion itself.

Cardin is then perceived as a kind of seer, ahead of the curve, able to capture and visualize the embodiment of the forward acceleration of fashion. Womenswear, with its passive-objectified (feminine) consumer, was thought to be the perfect arena for this innovation, and the market began to be driven by both fad and trend, something previously unheard of as an explicit retail strategy. The Future of Fashion (synthetics) had made this production possible; it had materialized a means of achieving speed through technological advances and technological fabrics and the standardization of fit. The marketing of clothes as standard sizes and bodies as the thing that needed the tailoring exploded. But this growth remained siloed and constricted to the women’s market. There was, as Saint Laurent’s Michel Zelnick said, the issue that designers felt that the active-subjective (masculine) consumer “would rather spend his money on his wife and children than on himself.”

[Image description: Black and white photograph. This image features the same black and white circular door which has been featured in two previous photographs in this essay. The picture itself looks nearly identical to the first image of the door, flanked by two male models in contrasting all-black and all-white outfits, but it is different. Unique but matching, consistent with Cardin’s philosophy of design. The models are in the same places as before, though in different outfits and different poses. They are still in all-black and all-white, and in the same color as before. This time they wear extremely high boots that are matching. The boots are patent and come all the way up to the thigh, where their narrow wool pants tucked into the top. They wear matching wool sleeveless tunics, the left in black and the right in white, with black turtlenecks underneath.]

Cardin recognized that this empathy for consumer desire needn’t be restricted to one half of the market. A true futurist, he saw the potential for growth at a larger, faster scale—at any and all costs. This is ultimately how Cardin’s shrewd taste, engineering-like attention to detail, and strict commitment to the futurist aesthetic earned him the reputation as someone who didn’t just create but knew the future of fashion, someone with premonition-like expertise on future trends and market capacities. Cardin becomes to the frustration of more conservative designers and critics like a fortune-teller, and to the delight of his devotees, he becomes a prophet.

In 1960, the anonymous fashion critic declared Cardin’s menswear look dead on arrival; within 18 months, Cardin had thoroughly proved critics wrong. Again and again, Cardin’s commitment to speed, progress, and futurism proves his critics wrong. Simple regurgitations of Futurist ideology were enough to convince the world that Cardin was somewhere between a fortune-teller and an oracle. Within eight years, The New York Times’ Style Section had convinced itself and its readership of Cardin’s unequivocal and strange genius—in an interview with Cardin called Cardin Discusses - “La Mode Masculine” published in the September 21st, 1968 edition of The New York Times, long-time Paris fashion critic and author Joseph Barry reflects on Cardin’s massive influence on shaping the future of menswear, something that the critic in 1960 was unable to recognize as a sure future of possible dress to come:

Six years ago, cannily anticipating the mature male’s joining the youth cult, Pierre Cardin introduced what he still calls the Stick Line, which one now recognizes as the pre-Twiggy look for men. … “What men most fear,” Cardin was told, “is that you will bring the bad habit of capricious, seasonal change in women’s fashions to men.” …

But as Cardin explains, his interventions in menswear were not capricious or disruptive at all, but rather the true return to tradition:

“Male fashions,” [Cardin] began—undisturbed but a bit distractedly— “used to follow the line of womens fashions, and even at the same rhythm. Often it was male fashion that influenced women’s. Yes it happened in the 1920’s, ceased in the 1930’s and started again—with my men’s line—in 1960. Everything began with that change. Now la mode masculine is discussed regularly in fashion magazines.”

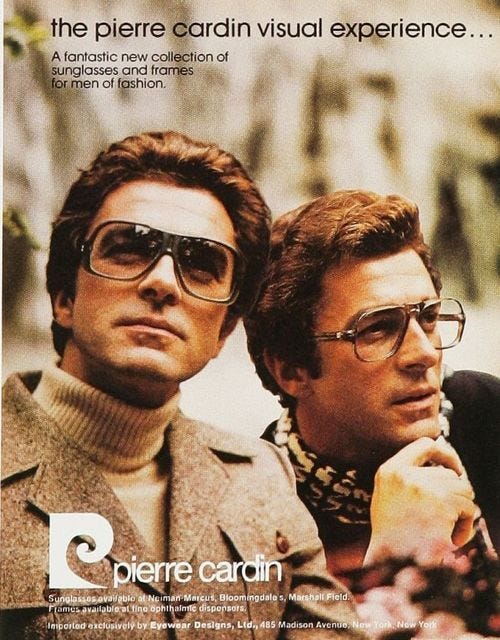

[Image description: Scanned advertisement, featuring a color photograph with superimposed white and black text. The text at the top reads: “the pierre cardin visual experience… “ in title-scaled text. Below the title, the subtitle text reads: “A fantastic new collection of sunglasses and frame for men of fashion.” The bottom text is a large Pierre Cardin text-logo with small info text underneath about various availabilities of the eye-wear collection, who carries it, and who has the exclusive import license. The photo under the text is two men, looking very 1970s in stylish seeing-glasses. They are both meticulously coiffed, with large poofy, blown-back 1970s hair. They both wear large 1970s glasses, made out of interesting colored plastic with large square frames. The man on the left wears a thick grey wool jacket with a military-style breast over a creme wool knit turtleneck. The figure on the right has his hand on his chin and wears a patterned top underneath a dark jacket. The first man looks up and away, straight at the camera but over it. The second man, with his hand on his chin looks to the right, out of frame.]

The critic, Barry, is unsatisfied with Cardin’s answer and pushes the line of questioning further, probing Cardin to respond more concretely to the accusation that his menswear line was responsible for feminizing male dress:

Barry: “Critics, and not only men, say you are feminizing men’s clothes, if not men” …

Cardin: “Refinement is not feminization, no more in a man’s thinking than in his dressing. I want to make people esthetic. … When I design I think only of the young, because only they have the courage to wear what is new. And the young are slim. A boy’s body is longer and slimmer now. Also if I design for young men, it’s because older men want to look younger. People don’t realize that I started as a man’s tailor.” …

Here you can see some classic Cardin eugenic philosophy, it’s important to remember that Cardin’s fascist future required all bodies to conform to his ideal physique. All bodies were to be made to fit. This to Cardin, was very much the future of fashion, a future where bodies would work for the clothes, not the other way around. Barry, reassures the reader that he fact-checked Cardin’s claim and was surprised to find it true, he, like the anon-critic before him, uses fashion phrenology to justify Cardin’s own claims about where his oeuvre should fall on the scales of history:

Cardin sent fashion reporters to histories of men’s fashions to see where he fits, and they do find in the Cardin look something of Second Empire elegance and turn-of-the-century, high-button style, the dandyism of Beau Brumell…

Here we have just seen another example of Cardin in his role of capitalist seer fashion oracle. He has pointed towards history as his proof that his designs are not, in fact, the degenerate product of the end of history, but rather the violent sign of history-Future:

Cardin is quite aware of the past if only, he says because he does not want to repeat it. Inevitably, in the cape, the flaring coat tail, the three-piece suit itself, he does. But the history of style, he insists quite rightly, is basically the story of a line. And he insists more strongly, he was the first to present men’s fashions as such. … Cardin had three words for men’s fashion in his own lifetime: “There were none. When I presented my line, there were only the eccentricities of youth.”

The critic, Barry, then turns the line of questioning explicitly towards the future:

Barry: “And the future of men’s fashions?”

Cardin: “I’m creating them now.”

[Image description: Black and white photograph. Pierre Cardin stands in a tailored “normal” suit on a Paris street, in front of a brigade of male models who are fanned out behind him, wearing his masculine clothes. This is an image from the same collection as a photograph that was shown earlier in this essay, which featured a man in full leather outfits, standing on a cobblestone street in dusty boots and a strange and geometric leather jacket. The men behind Cardin are in a range of matching but unique outfits. They all have high, dramatic collars on their coats, which range from a padded or quilted quarter-length wrapped jacket to moto-jackets and long-line moto jackets. The group strides forwards towards the camera dramatically in a militaristic fashion, the models are giving their full runway walks, and Cardin, in the center of them all, walks ahead like a general.]

Cardin at first would not respond to Barry’s question about the future of men’s fashion, but after what Barry describes as a very long pause, the answer that Cardin provides is pretty jaw-dropping in three ways. First, it so clearly reflects the ideology of high-fascist Futurism. Second, it is pretty on the nose in predicting the development of sportswear. And finally, third, he conceptualizes the violent destruction of the workplace uniform—a process which, in my opinion, we are watching play out in real-time during the COVID pandemic:

Cardin: “There will be a great deal of synthetics, molded to fit the body, perforated for breathing. Ties will be for formal occasions. … Formal and informal clothes will coexist, each a relaxing change from the other. Buttons will disappear, zippers can now be invisible and they follow the body more closely. Men will be entirely in color.”

Barry: “You are now,” it was pointed out.

Cardin: “Oh, much more violent. Blues, greens, reds, but very violent, as in other periods of the past. And I propose the ‘Cosmocorps.’ No, not only for leisure and country only. I did one in black for the evening. Don’t forget in 10 years the young will be 30 and it will all change.”

‘Cosmocorps’ was Cardin’s unisex masterpiece, a groundbreaking collection shown in Paris in 1966. Cardin described it as a genderless uniform, “strictly for the young.” Cardin felt that if dress did not shock you, it is “obviously not new”—simply a “pretty and immediately acceptable” garment imbued with nothing creative. To Cardin, the shock was necessary for design to transcend fad and shape the trajectory of trends—but also design was specifically for the very young to shock the prior generations. This is how fashion moves from dress to encompass a larger superstructural framework of aesthetic or lifestyle.

[Image description: Advertisement, black and white photograph with white superimposed text. A naked and muscular oiled man stands in front of a gray background holding a thick cylindrical bottle of perfume. Cardin liked to say that he thought the perfect masculine silhouette was cylindrical, tall and thick, and stick-like. That is translated here into the aesthetic of the 2000s, which makes the body-builder physique of the model so strange in the context of Cardin’s oeuvre. Cardin, unlike his predictions, was not able to grasp the aesthetics of the future, merely futurist aesthetics. The text at the top of the advertisement reads in lower case letters, “pierre cardin,” followed by, “eau de toilette pour homme,” on the line below.]

Many market researchers and industry experts have even credited Cardin’s cheap and selfish forays into the world of licensing (described by some as an undiscerning willingness to slap his name on anything) for igniting the explosion of contemporary interest in men’s fashion. This myth is told as if Cardin’s singular influence caught fire in the male brains of America and spread to the world, suddenly infecting the “men’s landscape” with a renewed fashion sense with the release of his Cosmocorps collection. This ignores the fact that nearly all designers (menswear or not) were deeply and heavily financed through cheap and selfish licensing deals, though they are often discussed as successes when designers like Ralph Lauren become too-big-to-fail bloated corpo-empires. Yet Cardin’s influence on menswear and, most importantly, the sell-ability of men’s fashion has been barely mentioned since his death, despite the fact that his work was instrumental in creating the luxury menswear market, which in recent years has gained even more yet-unprecedented market share.

Barry: “In the year 2000?”

Cardin: “I’ll be dead.”

The sad truth, as we all know, is that there is nothing truly rebellious or liberatory about fashion, nor will there ever be under capitalism. Fashion is only reflective of the actual real, cool, and strange source material from which it’s been so carefully and tastefully extracted.

And this, again, is not a value judgment; fashion and clothing make the world more beautiful. What sucks are the rules we tell ourselves about how we should or ought to dress and the money that is spent and wasted in the reproduction of garments that are always destined to be trash. Things can be beautiful, and things can be for everyone, but not if they are made with disposability in mind under the fascist futurist framework which has taken fashion from an exploitative industry of aesthetic social control and normalization and transformed it into a global network of extractive colonial corporate empires.