Finally, here is the second in my three part Pierre Cardin series. The first, HEALTH, discussed the ways in which aesthetics and fashion are used to control — to create borders between the “we” and “not we” — to mark who is important to capital and who is not. Next, in TASTE, we examine the classically convention-breaking Cardin silhouette as a perfectionist fantasy which raises larger questions about fashion’s ability to reproduce a powerful kind of social and physical discomfort. That discomfort can be revolutionary but it can also be exclusionary.

TASTE is a commodity but also a language, it is both a universal system of value and a singularity, belonging only to one individual in one moment in time and everyone all at once for all of history. TASTE is temporal, it is tethered inexorably to our current moment. TASTE is political, despite all attempts to depoliticize it. TASTE is also arbitrary, an absolute fiction subject to the social standards and morals of the ruling class. TASTE is violent, extractive, and appropriative, but it doesn’t have to be. To try to understand how TASTE can become more than simply an aesthetic means of reinforcing class hierarchies, it is important to first ask the question—what does it mean to be well dressed?

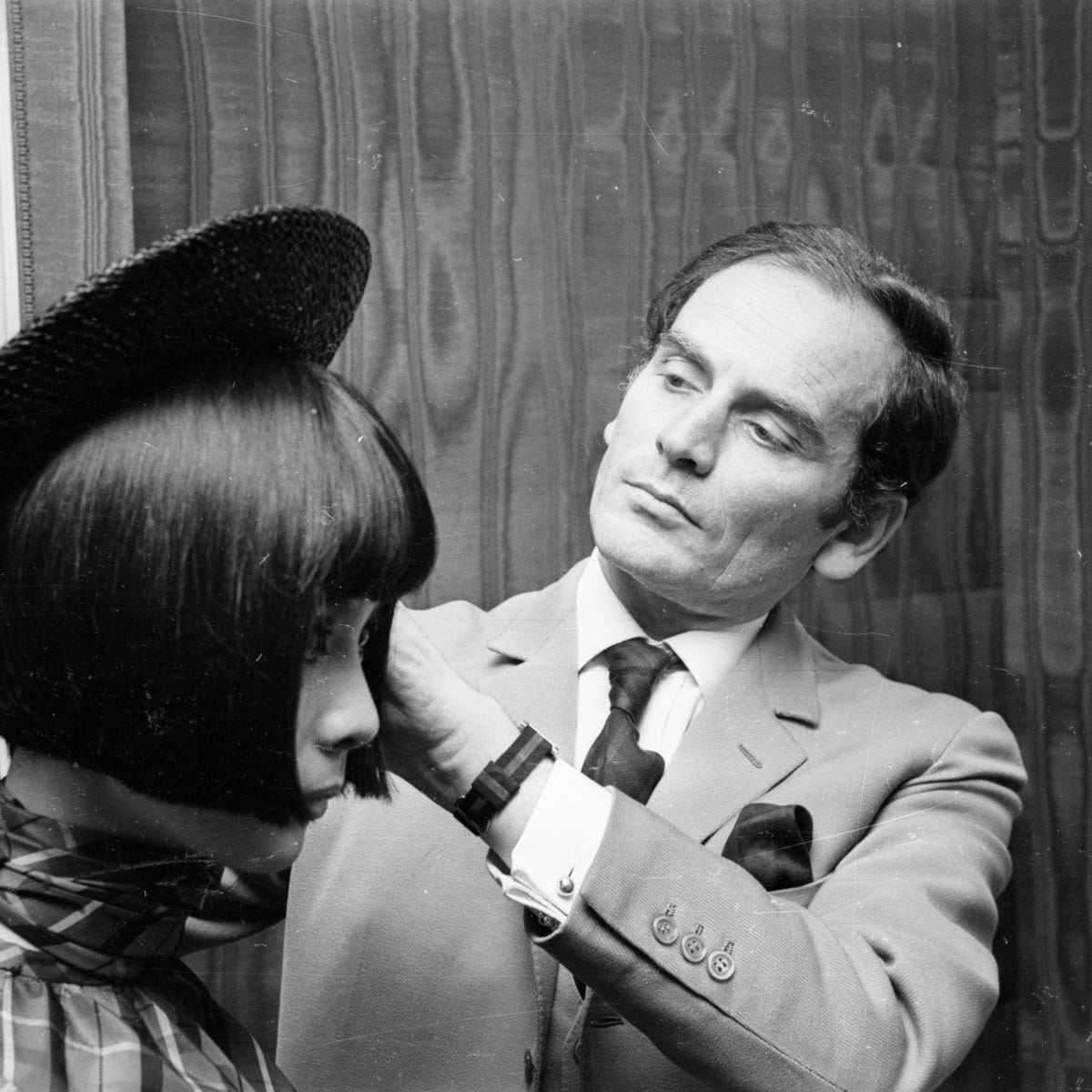

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. A young Pierre Cardin is fitting a model in a sleeveless black dress. Cardin wears a black woolen turtleneck, his black hair cut mid-length and pushed back behind his ears. He is concentrating intently on pinning a seam on the model’s right shoulder. His hands are caught in the act of placing the pin. His focus is total and his gaze is fixed on his fingers. The model stands in the foreground, wearing the black sleeveless dress. The dress has muscle-cut sleeves and a boatneck, and appears to be constructed of a thick double-faced wool. On the left shoulder, like a badge are the initials “PC” in white letters. They appear similar to felt patches like on a varsity jacket. The model is pretty and young with a clear face and dark but natural eye make-up. She is wearing a white wool hat with a signature Pierre Cardin look. It is shaped like a gumdrop, or like a helmet, with a smooth cut out framing the face. The model is smiling and looks off over her left shoulder, off frame.]

Is it important to be always well-dressed?

“I can define someone by the way he is dressed—if he is an intellectual, an artist, ordinary, refined. If he has good or bad taste. If he likes to provoke with colors. If he is discreet. We can define everything with clothing. That’s what’s amazing.” — Pierre Cardin

Pierre Cardin: TASTE

TASTE above all else is a judgement, one in which the criteria are perhaps the most strict and stringent of all such means-tested social relations. Pierre Cardin swore by his sense of judgement when it came to taste, and would frequently brag in interviews and other press appearances about how astute his taste-check radar was. Cardin was bringing beauty to the world; one hat, coat, glove, chair, pillow, silk, bathrobe, or fragrance at a time. Cardin felt that his ability to sell modernity came from the application of his unique insight into not only how to recognize taste, but to construct it whole-cloth out of thin-air, in order to disseminate it to a broad audience of people who lacked taste themselves.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Model stands, facing camera, with hands on her hips in two fists. She wears a tight black leatherette or poly-leather bodice made of surged wide horizontal panels. It is form fitting and shiny, but not patent. She wears a circular layered organza collar, shaped like several overlaid circles of increasingly smaller size. The collar is stiff yet playful, with light showing through in various densities according to how many layers of fabric fall under each ring. The edges of the collar come as high as the top of her head and down as low as the nipple line. Her hair is close cropped, with a light-wet look, tucked neatly behind her ears. Her eye make up is heavy and cute, with thick bottom lashes. Its a sort of idealized factory-girl aesthetic with a little bit of avant jester tossed in for good measure. She is smirking and looking at the camera with bright eyes.]

This may only be a mythology, a perfectionist fantasy forwarded by Cardin himself to justify his vast expansion into the licensing arena — but it is the mythology upon which most fashion business models are based. Cardin not only sold a beautiful, well-tailored vision of the future, he sold the permission to wear clothing that didn’t even look like clothing at all. Large and sculptural, many of his pieces defied the standards of silhouette.

Cardin thought that simply by looking at the way a person dresses, one can gather all you need to know about that individual. You can sum up what they are, what they might be, and who they are in relation to yourself.

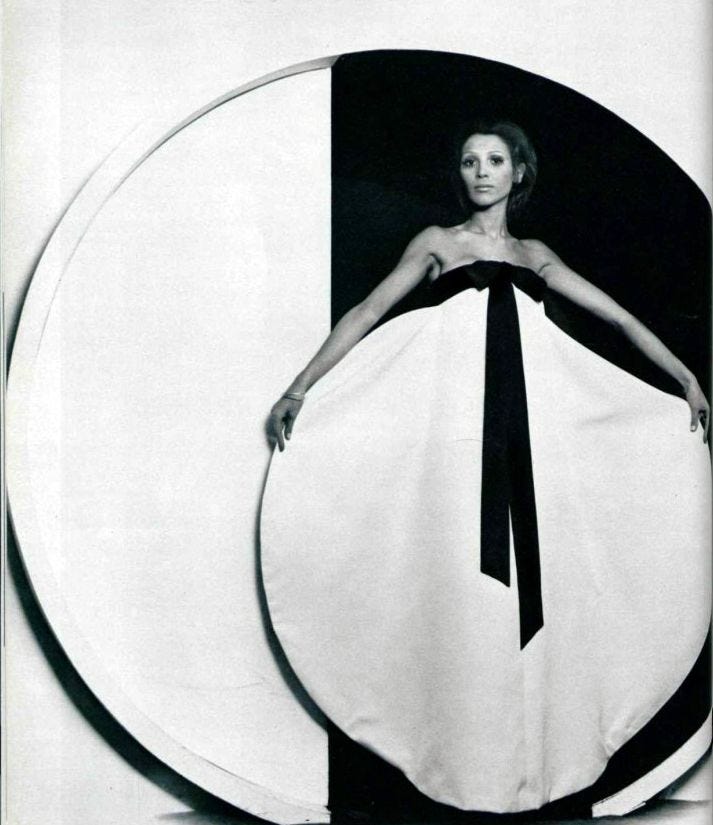

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Model in circular dress stands holding up the edges of her dress in front of a giant black and white circle door. She stands to one side of the circle, holding the edge of this large while dress to show its full shape. The dress is a perfect circle with the bottom edge just brushing the floor, and the top edge hitting right under the armpits. Around the top of the chest, where the white fabric connects, is a wide black band, which comes to a tie at the front of the dress. Two wide sashes drape down the front, the edges are angular like cut ribbon and the right sash is slightly longer than the left. To me this dress is reminiscent of a sales tag, hanging from the armpit or label of a dress. Or this dress is the stiff paper of a bouquet of flowers, tied with a stiff ribbon.]

What Cardin’s assertion takes for granted of course, is that his subjects have control over their dress. Most people, in fact, have very little control over the style of their dress on a day to day basis. This is just a fact of capitalism, but it also betrays something about Cardin’s world, and tells us a little bit about the kinds of people he was used to sizing up. It becomes clear that the working class has no room in Cardin’s imaginary.

In the vast wasteland of retail, these types of snap judgements are the currency of luxury sell-through. Taste-checks determine if an individual receives the salesperson’s time and attention or if they are ignored, or better yet, if they will be surveilled and followed by security throughout the store. This is because to Cardin, like to many other luxury fashion designers, taste above all else is a readable spectrum of discomfort which helps to determine if a body is in or out of place.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Model in white outfit walks down black glossy elevated runway, surrounded by photographers, editors and critics seated on the sidelines, busily taking in the show. The model wears wide white wool pants with bright, creased front pleats. The hem of the pants sweep the floor with black square-toed leather boots peeking out. On top, the model wears a wool trench-coat with ergonomic details. The wide collar is not pointed but rounded and flipped up to stand tall behind the model’s neck, framing her face. The lapels are similarly curved, with the coat coming to a tie, high at the waist. The pockets are large flat front pockets, with circular cut outs towards the top. Underneath the model wears a white ribbed turtleneck and a close cropped white beanie.]

To Cardin, it is of utmost importance to always be well dressed. Those who are not, are to him demonstrating their worthless-ness. To be well dressed, however, is not a guarantee that one is also fashionable. Fashion differs from dress in that it relies on a powerful intentional social and physical discomfort to drive attention. It is unusual that this visual system of determining and reinforcing class hierarchies relies so heavily on the disruption of norms as its mode of innovation. The more expensive the fashion is, the more cultural and political license to push the limits of what’s “normal.” Fashion, in its current form, is incredibly exclusionary, denying the same experimentation and freedom to those on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

“What is trashy on poor people, can be revolutionary on the runway.” In past posts I’ve likened this phenomenon to a kind of aesthetic gentrification. The permission to experiment with dress while still being considered to be “well” dressed is currently an exclusionary luxury commodity — but it doesn’t have to be that way.

Oublier la Fille

The taxonomy of luxury fashion involves a complicated system of archetypal “girls'' in which designers, brands, stylists, and editorialists traffic in various fantasies of the consumer. A this brand-girl “summers,” a that brand-girl is outwardly confident, those brand-girls see through you, a brand-girl is free, a brand-girl is dangerously cool and doesn’t give a fuck about stomping through puddles in thousand dollar boots. There are few archetypes as fake, as played-out, and as tired as the brand-girl. For many designers their brand-girl is simply, inexplicably “cool” in the dullest of ways. A brand-girl is not just a fantasy but a perfectionist fantasy, it is taste equipped as a kind of faux-necessary aesthetic heuristic.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Pierre Cardin, middle aged, wearing a light or grey suit with french cuffs and a dark silk pocket square adjusts a hat on his muse Hiroko Matsumoto. She has a close cropped and sharp black bob with blunt short bangs, which mostly obscures her features, her nose lips and chin peek out from under her dark smooth hair. On her head is a black straw hat which Cardin is adjusting. It is like a black woven halo, perfectly perched on the crown of her head. She wears a plaid silk top or dress, and they both stand in front of a satin backdrop.]

What is the Cardin silhouette?

“Like a tube, cylindrical. It’s very hard to make in factories.” — Pierre Cardin

Throughout his long career, Cardin had many different explorations of geometric shapes, which was only made possible through innovative tech fabrics. Cardin took inspiration from the space race, but borrowed not just from the aesthetics of space-futurism, but also from the appropriation of space-gear itself. Cardin, along with his aesthetic peers like André Courrèges and Paco Rabanne, revolutionized the materiality of dress in the 1960’s through minimalist, contemporary forms made with unconventional materials, such as plastics, silver, and vinyl. The Cardin-girl is layered and draped in nearly as many garments as an astronaut, her clothing becomes a kind of padding or armor, but also a signal that she is special and not only at the cutting edge but ahead of it.

“Cardin-girls” didn’t just organically gravitate towards the Cardin-girl look, the Cardin-girl has been given an ultimatum — dress well or be discarded. The Cardin-girl is decidedly out of place, the Cardin-girl is avant, her presence is dis-comfortable. Not a hair askew, not a seam unpressed, her dress is a wool circle, her eye makeup is heavy—the Cardin-girl is perfect, aspirationally more perfect than everyone else in the room, to the point that others feel discomfort in her presence. Cardin was at his best when his inspiration leaned towards rigidity and perfection, like his renowned 1964 Cosmocorps collection.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Lauren Bacall, Leslie Bogart and Alain Delon sit side by side at Pierre Cardin’s Fall 1968 Runway show. Other attendees are half-visible behind them, on the right of the picture plane are two models mid-show. The model in the foreground wears black, patent elbow length gloves with a houndstooth minidress. The dress is sleeveless and high waisted with a short hem. The bottom of the dress as well as a small portion of the bust in the center where a collar might be are geometric raised shapes, like square ziggurats sticking up out of the dress. On her legs are thigh-high black patent leggings, stockings or boots which come so high that they disappear beneath the hem of the dress. The model wears a black patent crescent moon hat on her head, which ties below the chin with a black grosgrain ribbon. The second model who is partially visible over the first model’s right shoulder is wearing a similar dress but in white wool. The second model is not wearing a hat and has a short cropped bob pulled back behind her ears. She is also wearing patent thigh-highs and elbow-length gloves, but they are not black. In the photograph they are a light grey, hinting that they could possibly be brown, tan or red.]

It is this mirage of perfection which Cardin relies upon to push the sculptural frontier of dress. Unjustifiable proportions are normalized through their economic context. It’s not weird anymore, only out of place in that it is stunning in comparison to all around it, it’s “drama,” it’s edgy. The problem arises however, not in the experimentation with silhouette and proportion, but in the exclusionary nature of access to it. The nature of how dress is commodified, relies on a deep and long history of exclusion. Because dress is, as Cardin himself argues, such a universal tool for social measurement, access to the forms which break the “rules” of this system are gate-kept through engineered systems of scarcity. That is the fundamental nature of the luxury market.

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Model stands in the center of a set which looks like a terraced cafe. The set is reminiscent of 1930’s femme-fatale silent film sets. Behind the model on the left is a table for two with white ornate chairs, the table is draped in white table linens, and set like a fancy lunch restaurant complete with a wine bucket and a bottle of champagne. There is a large white fringed cloth umbrella over the table turned upwards so that it is an open circle facing the camera. Behind the model on the right is a white wrought iron ornate streetlamp, with two of its several white globes showing, while the rest are out of frame. The model wears black short heels with black stockings. She is wearing a white dress or coat which when she turns, as she is in the photo, flares out to form a full circle. The camera has caught her mid-motion, as she twists, she gazes at the camera from behind her short cropped dark hair and heavy dark eyeshadow. The dress or coat has one large black circular fabric covered button at the center top of the chest and a black mink collar.]

To take the Cardin-girl and decomodify her seductive aesthetic transgression would be to disrupt just one of the many systems which elite power uses to reproduce itself. To break open the borderline of dress outside of the constraints of the market requires abandoning the construct of the brand-girl. An abandonment of perfectionist fantasies. A post-market fashion world would require new incentives and drives to fuel creativity, but I am of the mind that this reset would be incredibly generative — not much good has come of the current endlessly accelerating cycle driven by the dominance of fast-fashion.

Grève Esthétique

What if instead of allowing experimental dress to be an exclusive privilege of the rich, workers of the world went on aesthetic strike? Refusing the uniforms of our stations, classes, and trades—not in a silicon-valley-wear-flip-flops-to-the-office kind of way—but in a way that says yes to whatever the fuck you want to and feel like wearing whenever you want or feel like wearing it. Rather than be an embargo, the discomfort which fashion produces can be revolutionary. Cardin’s work is sculptural, transgressive, and playful — but it will always be limited by its context as a commodity and the exclusionary practices of policing populations through dress. How do we translate this kind of transgressive play outside of the context of scarce luxury commodity into a tool for the many? We can start by forgetting the brand-girl.

When designers picture their perfect girl, that creates an immediate boundary — a type of person who is not their brand-girl. One thing I’ve been trying to tease out in these essays, is how to expand the cultural imaginary of fashion, how to drop perfectionist fantasies in favor of liberatory dress? Forgetting the brand-girl is step one. Making room for designers to design without consideration to the market is step two. Beyond that… I have no answers, nor will I bow to the pressure of being made to think I must produce them. As Abolitionist scholar, Mariame Kaba, explains being forced to produce answers is a way of slowing down truly radical thought. Sometimes the point is not to have solid answers but to simply create pathways to break open the horizon and imaginary of what is possible in a way that moves towards building a better world, the how is actually immaterial to the broader goal:

It's always interesting to me to think about the how of things, the strategy of how we get from where we are to where we want to go.… “...people want to treat ‘we’ll figure it out by working to get there’ as some sort of rhetorical evasion instead of being a fundamental expression of trust in the power of conscious collective effort.” ...We’ll figure it out by working to get there. You don’t have to know all the answers in order to be able to press for a vision.

— Mariame Kaba, We Do This til We Free Us, 2021 (p. 167)

[Image Description: Black and white photograph. Model stands in front of two black wooden doors with four window panels each. The windows are full of safety-glass and reminiscent of an old hospital, school, or church. The model looks almost as if she is wearing a really chic modern nun habit. It is a triangular hood which comes to a point at the top of her head, it flares out along the shoulders, coming down to elbow length. The hood is white woolen fabric, thick and holding its shape, with large black round covered buttons. The bottom hem of the hood/cape is a thick band of black wool. In the back, the cape is lower than the front, scooping back and falling lower than the elbows, out of frame and obscured behind the model’s body. The model looks down at the camera, her eyes have heavy black make up and she half smiles with her hair pulled back tight underneath the hood.]

The history of fashion from the mid 20th century onward was one of increasing commodification, and stratification. More so now than ever, the quality of a person’s garments are evidence of their class position. It is in this context to me that Cardin’s groundbreaking experimentation rings hollow and flat.

Sometimes the point of fashion is to make people uncomfortable, and to learn to love discomfort. I don’t mean to say that fashion is about adapting to uncomfortable circumstances, it’s more that fashion is a call to embrace social discomfort as a generative, creative, and radical space, not as a stimuli to react against. The point is to shock, to be looked at, to push the boundaries a bit. This kind of playfulness with form, the subversion of the silhouette for rigid geometry, is primary in Cardin’s work. Cardin’s is a kind of total aesthetic vision that is rare to find in the current crop of design talent. What a deep and true shame it really is that we dole out this precious permission to break conventions of form and function with such austere and limited access in mind from the start.

The point of radical silhouettes is not to wear them until they become normalized, and we all become comfortable with geometric dress. It is to embrace the social phenomenon created by the discomfort of radical dress and revel in the discordance that it creates between the wearer and their context. This juxtaposition, and the cultural permission to embrace (and celebrate) this kind of play-with-dress is currently something only granted to select few. Breaking exploration with dress out of its classist context offers so many more possible futures for the way the world around us looks. We do not need to be tethered to arcane and neoclassical aesthetics, its ok to embrace uncomfortable and modern shapes in the everyday, and importantly to do so across price points, rather than continuing to reproduce the concentration of avant in the scarce context of elite privilege.

The third essay in this three-part series on Pierre Cardin, called MAN will follow. Read the first — HEALTH.