The Tricky Politics of Invoking “Resiliency” in the Context of Disabled Palestinian Children Enduring Eliminatory Settler Colonial Violence

Instead of celebrating resilience in the face of annihilation, fight for a world that doesn’t ask disabled Palestinian children to “adapt” to genocide.

“All too often, Palestinian ‘resilience’ is over-rated and sometimes used as a means of avoiding acknowledging and addressing the issue of injustice to Palestinians with humanitarian and international support divorced from the calls for justice, as happens elsewhere. Nevertheless, at least, resilience implies ‘what is right’, instead of ‘what is wrong’, often identifying and describing Palestinians in dichotomies as either terrorists or victims (and we do not accept these labels) or by counting dead bodies, injuries and disabilities. From a public health perspective, it is the survivors of exposure to political violence who are our priority. And this includes not only the injured and disabled, but also all those with trauma’s invisible wounds. Such survivors oscillate on a continuum of ease-disease back and forth daily depending on the degree, severity and chronicity of violation and capacity to endure and resist. This is our definition of what resilience is about, not just bouncing back to where people were before violation…” —Rita Giacaman

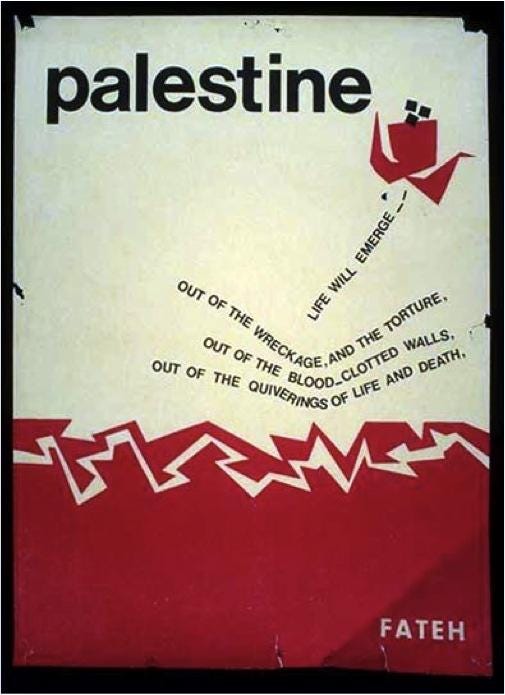

[Image Description: Photograph of poster from the Palestinian Poster Project made by the group Research in Progress circa 1973. The poster is red and white and is a geometric abstract depiction of a flower growing from soil. At the top is black type that reads: “Palestine” And part of the design includes red type which cascades down the page and reads: “Out of the wreckage, and the torture / Out of the blood-clotted walls / Out of the quiverings of life and death...life will emerge.”]

Stop Calling Disabled Palestinian Children Resilient: Instead, Fight for a World That Does Not Ask Them to ‘Adapt’ to a Genocide

You might have seen, or will see, a post or article going around sharing the fact that Gaza has the largest concentration of child amputees, and I want to talk to you all about how to talk about this and share some resources. As someone who both lives with and studies debility, I have thought too much about how language can shape the political economic reality of impairment at a collective level. That is why I want to encourage you not to so readily apply the label of ‘resilience’ of the many tens of thousands of Gazans who have been injured or disabled in this brutal escalation of an ongoing genocide.

I am not bringing this up to police language, or to say that the focus of your attention should be outrage over the use of certain terms. Please don’t waste your time on that. Palestine needs us to escalate. I am raising this issue because resilience in the arena of disability is often used as a veneer that papers over systemic harm with a celebration of an individual’s plasticity—there is a similar function this word plays in the context of Palestine. We owe Palestinians more than this accommodating and passive framing of their capacity to endure and resist genocide with “enthusiastic pessoptimism.”

At the end of this post, I’ve shared some advice from a Death Panel podcast guest, Rasha Abdulhadi, about some more useful outlets for your shock, sadness and outrage than getting pedantic about language. For that matter, please check out all three episodes of Death Panel that feature them. Rasha is a wonderful person, and a joy to talk to, and their words will help you move past what might be holding you back or weighing you down right now.

[1] Refusing Genocide w/ Rasha Abdulhadi (10/16/23)

[2] A Killing Peace w/ Rasha Abdulhadi (Part One) (04/18/24)

[3] A Killing Peace w/ Rasha Abdulhadi (Part Two) (04/25/24)

Why Does it Matter What Resilience Means?

“...All too often, Palestinian ‘resilience’ is over-rated and sometimes used as a means of avoiding acknowledging and addressing the issue of injustice to Palestinians…” —Rita Giacaman

As the Palestinian public health scholar Rita Giacaman writes in her article “Reflections on the meaning of ‘resilience’ in the Palestinian context,” the lens of resilience is often used to describe the personal and collective response to chronic and protracted exposure to settler colonial violence at the hands of the Zionist state within public health literature, especially that which touches on the study of “mental health.”

At the beginning of her article that I’m citing here, which you should read—it's short and fantastic, one of many excellent pieces of scholarship she’s done on this topic over the decades—Giacaman says that for all of the work that is done in this area specifically looking at the context of Palestine, “we have not been able to locate a word in Arabic to fully express the meaning of the English term. Some translate resilience to Sumud (steadfastness, meaning sticking to the land), others to Jalad (meaning ability to withstand), or Muruneh (flexibility) or thabat (pliability), and yet others call it alqudra ala attahamul (capacity to withstand).”

In psychology and psychiatry, resilience is described as both a process and an outcome of successfully adapting to challenging life circumstances. Giacaman notes that in Arabic, adaptation means accepting the situation without addressing the root causes. Hence its absence from these attempts to translate resilience into a Palestinian context.

When Giacaman began working during the second Intifada to try to understand and translate the meaning of the term “resilience” in the Palestinian context she found that many of the international and dominant framings of the term did not fit. Instead she insists that we must think of resilience not as an inherent quality that is constant but as episodic, as the capacity to endure and resist, non linear and something which is not a raw ready resource, but that which takes work to build.

This true resilience can be visible as joy but it does not exclude feelings of distress, low quality of life, depression, fear, worry and humiliation. Many conceptualizations of resilience ignore what Giacaman calls it’s key component—communal care and support. The collectivity of the exposure to violence is met by the many interlocking and overlapping collectivities that sustain the capacity to endure and resist.

Giacaman continues, “We have over time collected an array of Palestinian colloquial Arabic words as opposed to classical Arabic...expressing particular health states, at particular moments in time. For example: hamm (hamm is embodied and can be seen as someone who is carrying the weight of the world on her back) and ghamm (also embodied where someone’s bodily expression looks like someone is about to explode); or sammet badan (poisoning of the body, also embodied) and ghull (could be rancor, could be hatred, could be burning thirst depending on how it is used). Sometimes it takes several words in English to explain the meaning of terms used in Arabic, and even when using several words, meaning is not quite understood as it is understood in Palestinian Arabic. More, how people express distress and ill-health/ill-being is usually related to a particular way of knowing, of being and of doing, which are embedded in context and culture.”

I think this is a fascinating observation that I try to always keep in mind when communicating in all of my half-Arabic half-English group chats. Google translate is supporting these relationships, but it also can literally put words in our mouths that do not mean exactly what we say. And often these words carry the subtle legacy of Zionist violence, which gets at why ‘resilience’ is a concept white settlers in the imperial core shouldn’t be so quick to label people with. What becomes resilient in translation can often mean something that is overall different.

But this doesn’t just happen by accident, when you say a disabled Palestinian child is resilient, do you mean that they should successfully get used to forever-genocide? I hope not. I hope what you mean to say is that you cannot comprehend what it would be like to be surrounded by so much ongoing collective and individual violence. That it is intolerable to you to see people being put in this position. That you are impressed by what you are witnessing from a child with the capacity to resist and endure in the face of overwhelming violence. That you are inspired and look up to this child but you are also disgusted and horrified that this is really happening to them. You may also feel powerless and want to bolster yourself to work up the courage to act in solidarity with Palestinians.

If that is the case, and you do not mean that you wish Palestinians to endure another 100 years of settler colonial violence—then say what you mean. I guarantee it is more powerful and persuasive than invoking the concept of resilience, implying adaptation.

Hope and Despair are not Opposites

As Giacaman and many other researchers have found, collective exposure to violence, independently of individual exposure, has negative health consequences. Even Palestinians far from the Strip, who have gotten through the border crossing out of Rafah, or who have never even been to Gaza experience the effects on health downstream of exposure to the ongoing settler colonial violence in Gaza. For those experiencing the daily direct individual and increased collective violence of life in Gaza the effects are compounding.

One thing Giacaman points to is the role that collective care and communality plays in assisting and sustaining Palestinian resistance. Collective care means seeing others’ well-being and survival as a shared responsibility, not the sole responsibility of individuals. Beyond that it is a commitment to do it all at once: addressing interlocking oppression and dynamics in groups that have a negative impact on well-being, while also fighting oppression at the systemic, societal, or political economic level.

Gazans I am in community with all have spoken with me about one topic in common: deprivation. It is pervasive and inescapable. However, it is not automatically endurable, and how it becomes so is often a topic of conversation. The capacity to endure must come from somewhere, and often that resource is replenished only with community care and resistance.

My friend G says there is no difference between hope and despair, to him they are the light and dark sides of refusal. My friend S says that above all else, it is the relationships with people outside of Gaza that help keep her going. Because for so long has been a high priority for the Zionist entity to stop the formation of these relationships, every single one of those relationships, she says, therefore feels like a small but meaningful contribution that sustains her, gives her life just categorically beyond the content of the friendship which is also important.

I often hear from listeners who worry that they are not doing enough, or that their actions don’t have meaning or do not contribute to the goal of liberating Palestine. I rarely am good at staying on top of communications so I thought I’d quickly send this post out instead. First, thank you all for the kind messages, I wish I had the capacity to reply to all of them and am working towards finding the capacity for that. It reassures me that the Death Panel community is so thoughtful and attentive to the ways that resistance and agitation are coopted and blunted. I think it’s right to be constantly questioning if your actions are aligning with the ultimate political goal of a free Palestine.

My friend Afnan, a healthcare worker who you heard from on the water crisis in Gaza in the most recent newsletter, said something the other day that might bring listeners struggling with these questions some comfort. She said, “The one and only solution is the end to the settler colonial occupation. But, your presence by our side, your voices that ring out in the marches, your support and your chants make us feel safe. We feel that there are people in the other part of the world who feel for us.”

So my best advice is actually very simple. Don’t engage in commentary, build relationships and take responsibility for each others’ well-being. Do not relent, escalate.

What is to be done?

Finally, as promised, here is a quote from one of our Death Panel podcast episodes that is an interview with Rasha Abdulhadi. In this quote, Rasha offers numerous ways to get involved or deepen your daily commitment to Palestinian liberation. In addition to what they shout out here, I want to also shout out gazafunds.com — a website that is aggregating fundraisers from folks in Gaza and randomly features one that needs support every time you refresh the page. Gaza Funds needs people to step up and “adopt” fundraisers, which basically means taking responsibility for sharing and promoting and telling people about it, helping that person meet their goal, and being there with them to help them in the way that only community care can.

Gaza Champions is running a similar project and is also looking for people to volunteer to adopt campaigns: https://www.championgaza.xyz/volunteer/

Two fundraisers that I am helping out with are for water infrastructure repairs in Gaza — bit.ly/GazaMuni and for my friend Afnan Abu Hasaballah — bit.ly/HelpAfnan

That’s all from me for now. Tomorrow we have a great episode for you coming out in the Death Panel podcast main feed, where Phil, Abby and I critically read that heinous article in The Atlantic that went around with the line “it is possible to legally kill children…” — surprisingly it was a more enraging conversation than I imagined it would be. I hope you all love it, I know people tend to enjoy it when we really lose our temper on mic and that certainly was the case with this episode.

Now I offer you this excerpt of the second half of my conversation with Rasha Abdulhadi from April. Remember: don’t just witness this genocide, refuse it.

…Rasha Abdulhadi 55:08

I do want to remind people about some actions I've talked about before, about actions that we have witnessed other people take, about actions you may not think about as actions that are valuable and meaningful.

So as a Palestinian with Long COVID, who isn't able to be in the streets, or in physical spaces of organizing in the ways that I'm used to, I'm doing a lot of relational work. And that work is very important. I'm also doing counter propaganda work.

And I encourage other disabled folks, other folks who are organizing around COVID, to really attend to the value of the counter propaganda of the sick bed, both in the sense of the counter propaganda that can be produced by people who are disabled, house bound, bed bound sometimes even, and also the counter propaganda of just being disabled, and refusing and being unable to participate in the death making of the economy, wherever possible, and to really embrace that refusal as something powerful.

And of course, people continue to organize and go to protests and know that they matter. And they matter not just because a protest leads to a particular specific outcome, but because we are practicing being together, and we are practicing disobeying. And that is good. And there are other skills that we might build and other relationships we might build that might make other things possible. So keep doing those things and practice COVID safety together when you do them.

Practice masking and testing and sharing resources and teach and share and distribute paper bags with masks so that people can learn how to do rotations, and not have to use a new mask every time. Turn towards the friction in your life where people don't want to talk about Palestine.

That's where it matters to talk about Palestine. When you're in a room and no one has said Palestine. When you're in a room and no one has talked about the still ongoing pandemic. Those are two things I am often the first person to bring up in a room and that they are both unmentioned feels so telling to me, so clarifying. Be the person to mention both of them.

When I think about who deserves critique, I also think about practicing redistributing discomfort upwards, like trying not to wear out the people who I want to be in struggle with and be in community with, but really aiming my critique and my troublesome behavior towards people who are in decision making positions or positions of power, in which they might feel isolated from the consequences of being complicit in genocide, either by their calculated silence or by their active support.

And you can refuse, you could quit a job in this genocidal administration, instead of writing all those anonymous memos. Just quit, leave, go, get out. Abandon your post. Desert.

Any choice of refusal would be better than participating. Your participation does not slow the death machine. You are not moderating it. Do not lie to yourself.

Do not think that you're going to release these anonymous memos as your collateral character testimony in The Hague, that this is going to save you from your active participation and your enabling of genocide.

If you are serving in this current genocidal administration, what is in your heart does not matter. Get out. Leave, leave, leave. Unless you are literally throwing gravel into the gears, or pouring sugar into the gas tanks, then get out.

You know, there have been some folks organizing around renunciation of citizenship in the settler colonial state and after recent bombardments of the settler colony, there have been increased flights exiting the colony. Don't you dare take anyone seriously who describes themselves as being in support of Palestinians but still uses the name of the settler colony to describe their own identity or affiliations.

They have not unlearned settler colonialism or ethno supremacy yet. Tell them to renounce that citizenship and leave behind, shed like a cicada their identity as a settler.

Blockades still really matter. Wow. Pay attention to the blockade work of ports and the ZIM ships being done around the world, but especially In Australia, the so-called Australian colony, really powerful, multi-community, indigenous, Palestinian and other folks blockading, and those are not necessarily big actions.

Those are not multi thousand people marches. They could be, but it doesn't have to be that big to be a blockade. If you've never posted a sticker in a public place, or like posted a poem in a public place, or like distributed some zines in a public space, try something like that.

I'm going to share a list of writing prompts and action prompts that I wrote at the invitation of the Radius of Arab American Writers for this month, which is Poetry Month, National Poetry Month. Some poets are celebrating it as Nationalist Poetry Month, but we don't have to be those people. We can think about ways to bring our words into relationship and into public.

Try wheat pasting, try stickering, try cultural jamming, engage in mutual aid, whether that's donating to mutual aid funds for Palestinians staying in Gaza to feed each other, to keep each other alive, whether it's for evacuation funds, especially for children to reunite with family, for people who have medical needs and need treatment outside of Gaza. Those are valuable.

Don't get too hung up on whether you're getting scammed, like morally, is that what matters to you right now, like in all the risks you could take in the world, if you are someone with a home who can afford to feed yourself and have whatever medication or healthcare is a baseline for you, then -- and I know that that's actually such a huge bar to clear that not very many of us do. I don't. I still give.

Give money, give it freely, give it without worrying, in the same way that you should give money to people when you see them in your neighborhood. Just give them money to stay alive. You don't have to know what happens. You don't have to run the equation to figure out whether that's the most impact. Those are some ideas about actions. Certainly, boycott, divest, sanction.

People who are in artistic and cultural organizations, in scholarly and academic situations, you can work to push for the divestment of endowments and budgets. Those are long fights. You should study other people who are in those fights. I've written some about that online.

Don't fool yourself that moral argument is enough, that the material argument is important. It should be costly for people in institutions to be complicit in genocide, or to profit from it passively. I don't think we should expect that a moral appeal will be enough, but we should make it impossible for them to do.

There's another thing that I want to add in the links for the show notes that's an option to think beyond the cultural boycott, which I think is a great training wheels for some people who have never thought about saying no to collaborating with settlers.

So that's a good practice to just develop a habit to not automatically say yes to settlers. So PACBI, the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of the settler colony is worth engaging with as a sub -- as a floor, not a ceiling, as maybe a sub basement floor.

But The Public Source, which is based in Lebanon, Lebanon, created a commitment in July of 2023 that for them was about rejecting Creative Commons, and really embracing orienting more towards a duty of care towards Palestinian lives. And I've been talking with folks about looking at that statement, which is really thoughtful, as a way of thinking about going beyond PACBI, of going beyond the sub basement floor of a cultural boycott of the most heinous military affiliated cultural institutions and individuals, but really embracing what we might call a positive peace of a more community care perspective, of focusing on what it would take to actually keep Palestinians alive, rather than just checking off some sort of papal indulgence to get out of feeling guilty for being complicit in genocide. We are all complicit.

If we are not in Palestine, we are all complicit, and we have a responsibility to fight it. …

(listen to the whole episode with Rasha here: A Killing Peace Part One & Part Two)