The Body Illegible

Capitalism has no future worth preserving…

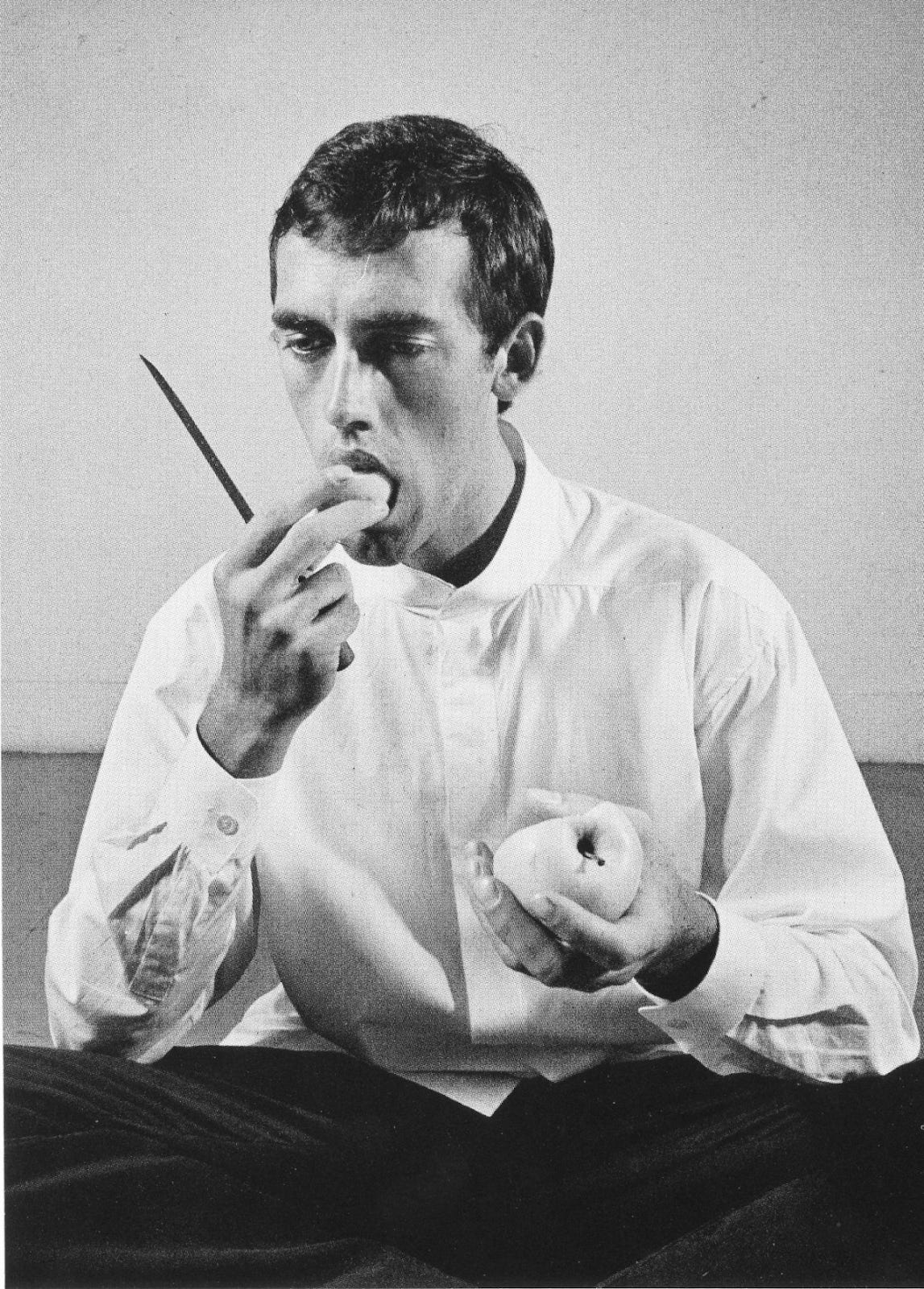

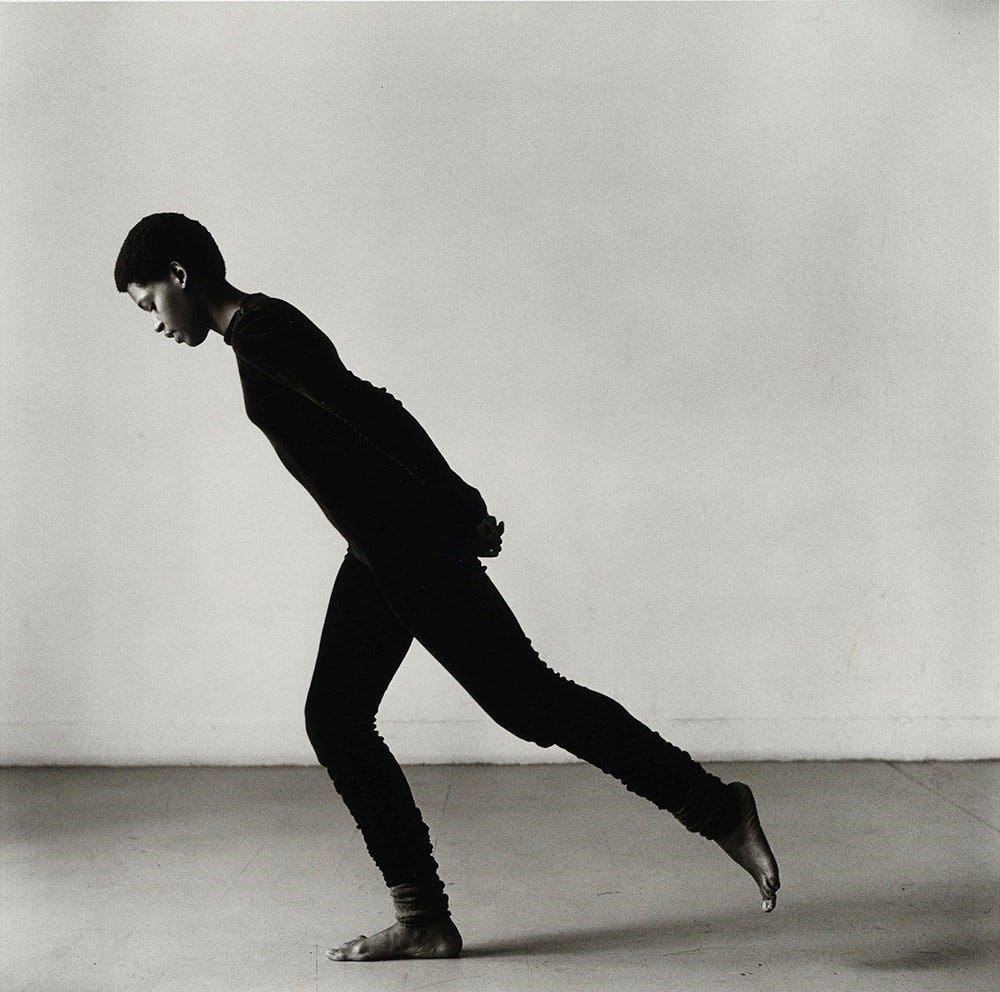

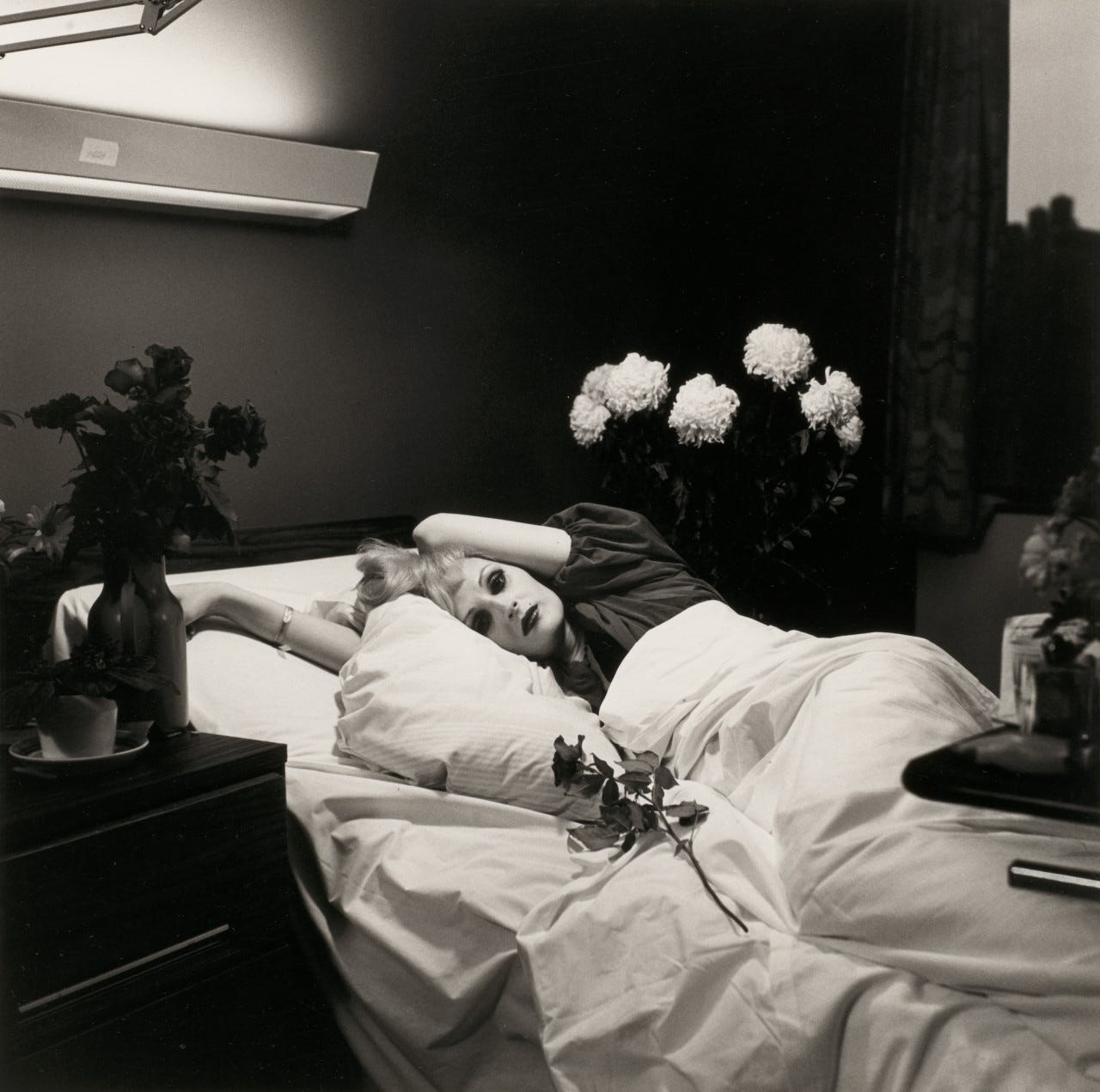

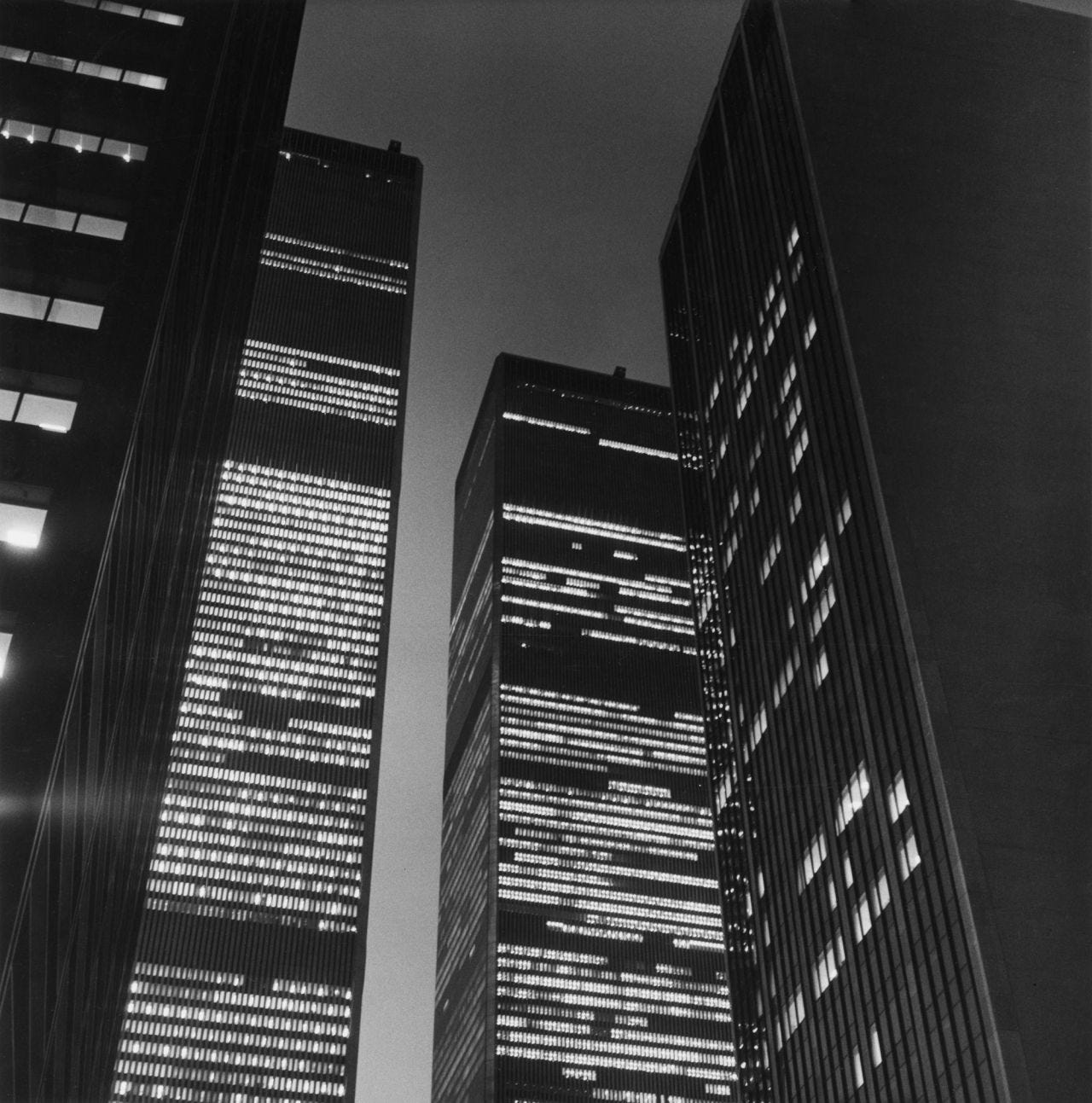

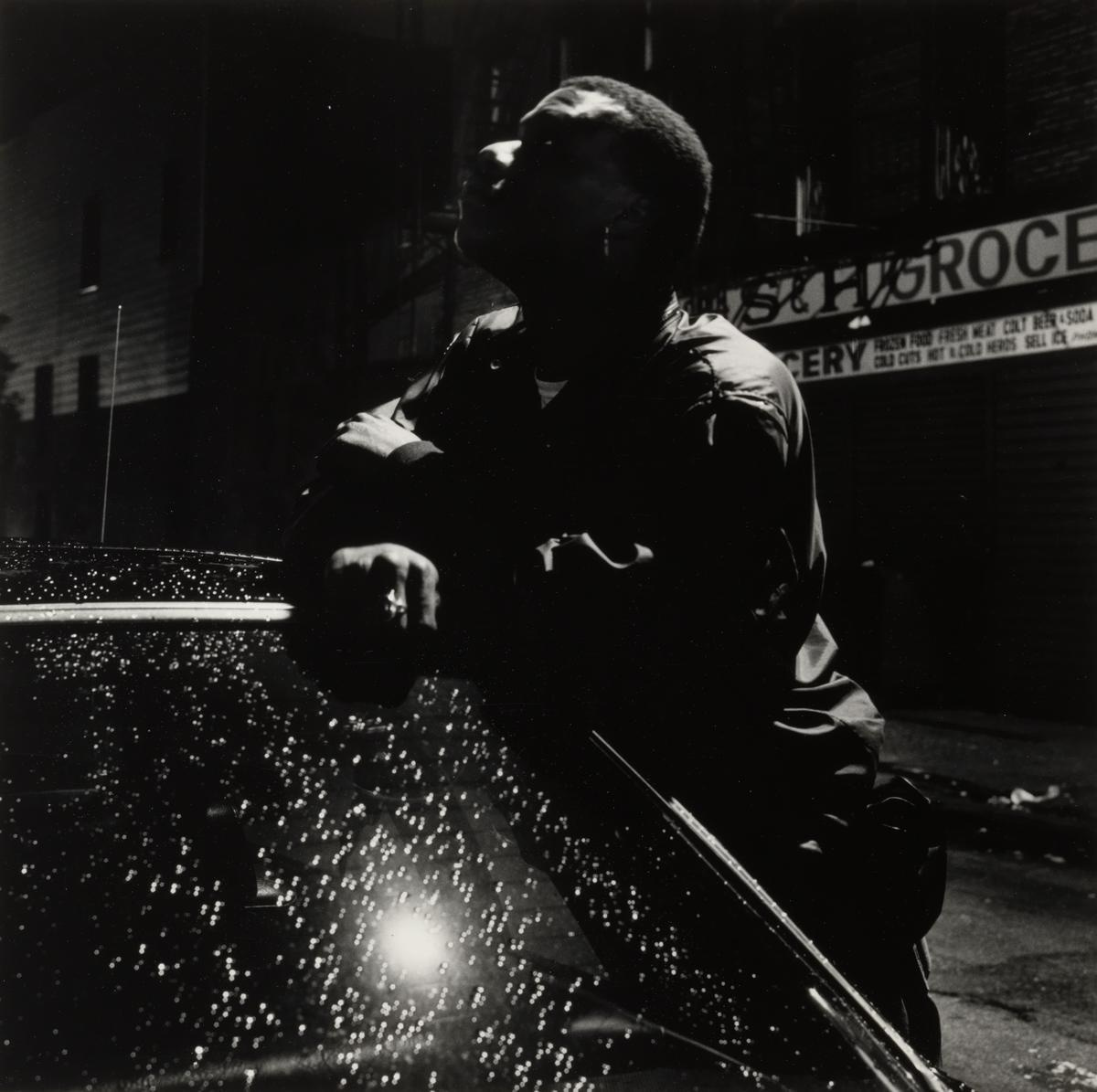

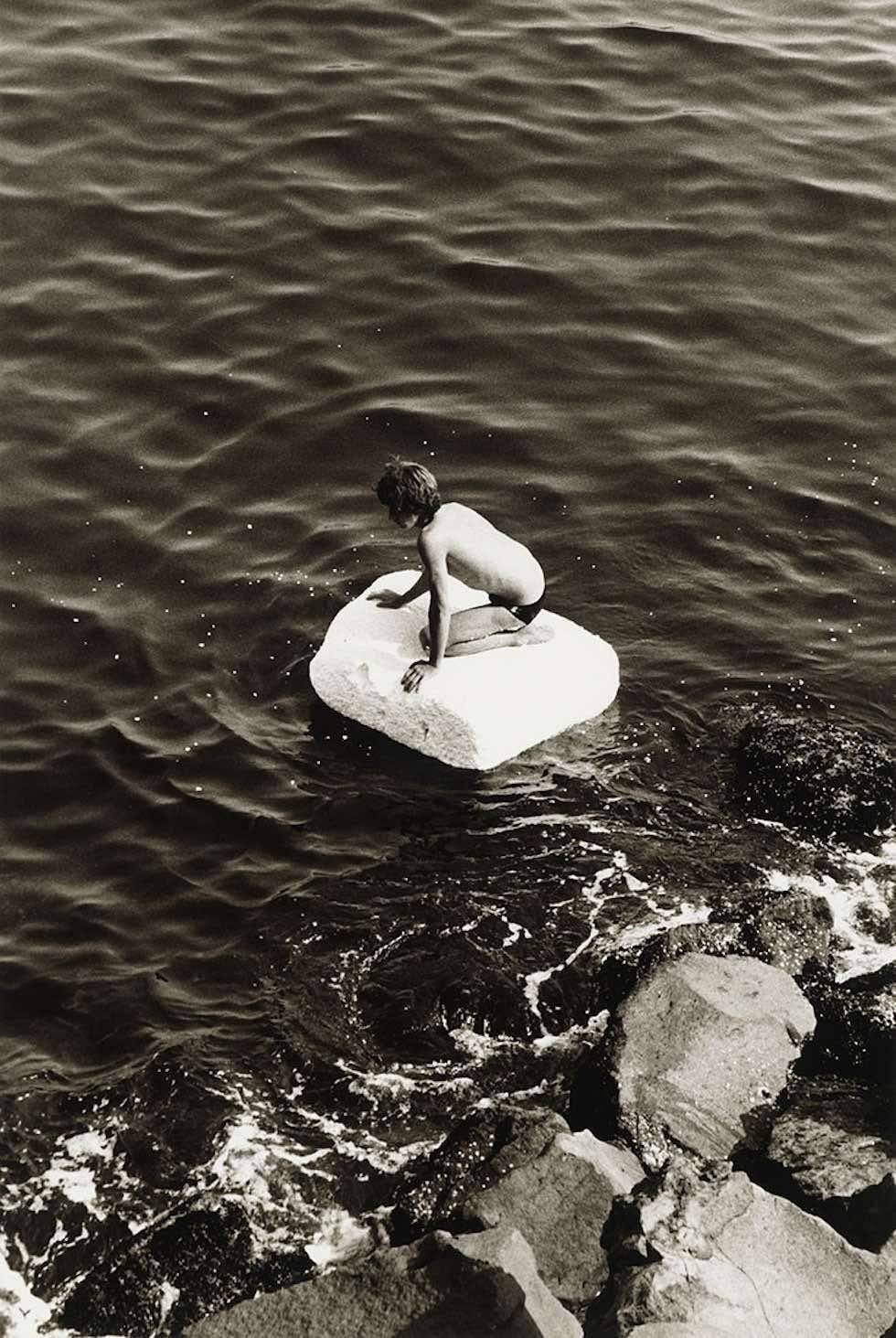

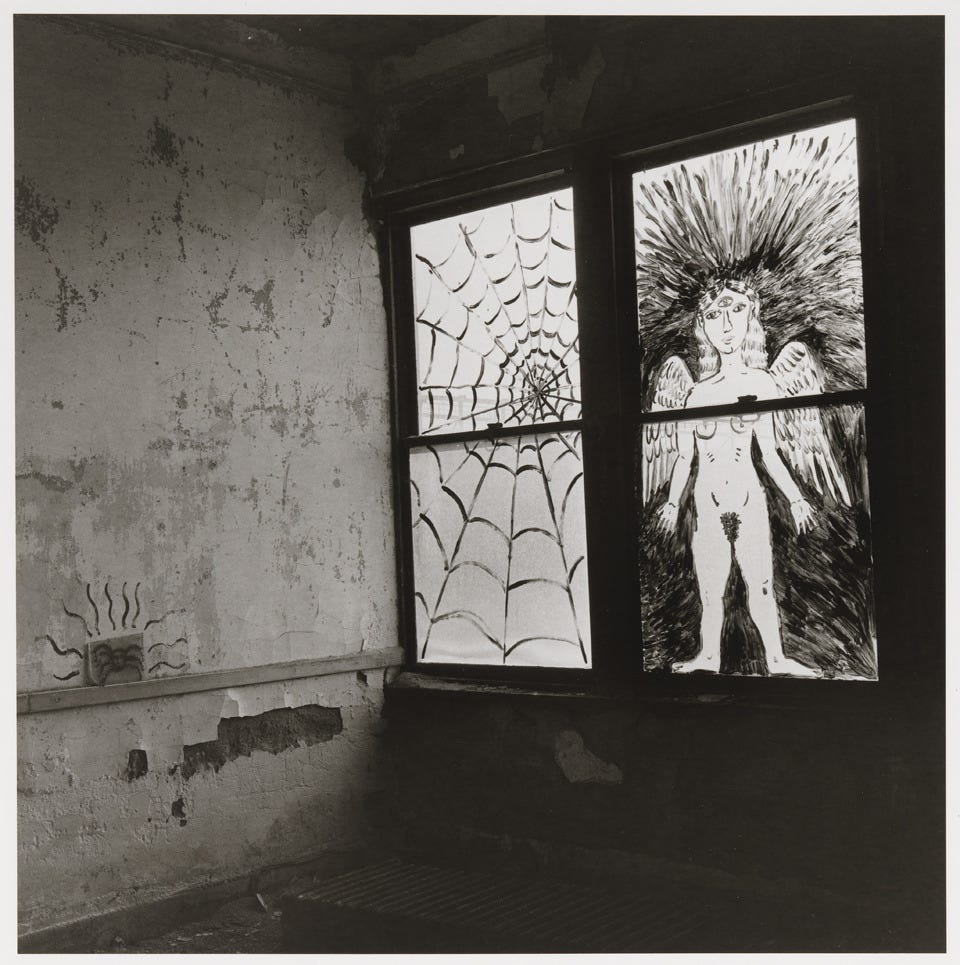

This essay is part of an informal series that applies core Marxist analysis to disability, chronic illness, and the political economy of embodiment. The photographs sprinkled throughout this essay are all by Peter Hujar. Hujar devoted his practice to black-and-white portraits, and his work often meditated on intimacy and mortality, particularly as he documented friends during the AIDS crisis—which he died of in 1987.

The Body Illegible

Capitalism has no future worth preserving…

Recently, on one of the Fox News Sunday shows, the head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dr. Oz, offered a familiar refrain: “If you really want to drop the cost of health care in America, get healthier.”

It’s a neat enough soundbite, tidy enough to fit the format (dodging the question, deflecting accountability, and saying something outrageous that nevertheless reads as common sense to the average viewer), but it rests on a lie that has shaped U.S. health policy for decades—the idea that individual bodies are the primary drivers of health costs, and that the solutions lie in personal discipline, lifestyle tweaks, or moral resolve. This lie is Dr. Oz’s whole brand and it works by pretending that social conditions are background noise, that the economy is a separate domain, and that the body’s suffering can be understood without naming the forces that produce it.

This ideology treats the body as something standardizable, readily measurable, controllable, and—perhaps most importantly—legible. An isolated machine whose failures can be quantified, corrected, or disciplined. Calories, cholesterol, blood pressure, steps taken, miles walked, minutes standing, hours slept: all proxies for “responsible” living, all taken as evidence that health is a matter of individual choice rather than social context. Under this logic, the political economy is made to disappear. Labor exploitation, environmental ruin, structural neglect, unequal care are all invisibilized variables, treated as largely irrelevant to the body’s condition in the mainstream of health ideology.

The state, insurers, and cultural authorities alike reinforce this framework of legibility. They insist that health is a personal ledger to balance, never the product of collective conditions. Couldn’t be an issue of material infrastructure. The organization of life under capitalism always seems to escape the blame. In other words, the body becomes legible only insofar as it can be abstracted into numbers, metrics, and moral judgements, severed from the social and economic forces that shape “health” as if the body exists without the political economy which is its context from the cradle to the grave.

But the body is never outside political economy. It is the terrain on which political economy is lived. The body is not a passive recipient of social forces; it is the living medium through which capitalism reproduces itself. Every body, every limb, every organ, every cell is shaped by a society that organizes life around one overriding priority: the accumulation of capital.

The workplace, the environment, the clinic, the hospital, the home, the economy, the state, the prison industrial complex, literal policing and the policing of who is “productive” and who is “excess”—all of this and more shape the body long before personal choice ever enters the picture. To talk about “getting healthier” without reckoning with this is not just naïve; it’s a misdirection that keeps us looking inward when the real forces of sickness move outward, through the structures that govern our lives.

Health and illness are not neutral states of being. I’ve said this so many times now you guys are probably sick of hearing me say it. This is the central argument of Health Communism after all. Health and illness are social positions—at once both machinery and loci of surplus value—forged within a system that measures worth (value) through the lens of dominant markets, and treats anything (or anyone) that cannot be commodified as peripheral, burdensome, frivolous, or disposable (waste).

The devaluation of chronically ill and disabled people, or even someone who is just temporarily under the influence of illness, is not an anomaly or ignorant mistake. It is the calculus of a system that is designed to be intolerant of fragility, to deny interdependence, and to rigidly ignore the unpredictability that defines human life itself.

Value-form theory gives us language sturdy enough to name this structure. It reveals that capitalism is not merely an unfortunate economic arrangement with incidental negative health outcomes. Capitalism is a form of society subsumed by the logic of value, governed by it. A logic that determines what counts as ‘real,’ what forms of life are encouraged, or even allowed, to endure, and what (or who) counts as waste.

Though we often talk about health as if it has the same meaning to all of us, health is by no means a universal ideal. However, it is universally a requirement for participation in the circuits of labor and exchange. Disability, debility, impairment, and illness (even temporary) offer contrast, marking the boundaries of what is ineligible and illegible to capitalism, revealing the limits of a world that pretends to honor life while treating the conditions for life as irrelevant unless they yield profit.

That is why today I’m going to attempt to offer a sustained value-form analysis of health, illness, impairment, chronic illness, debility, and disability. Before we get into the meat of it, I’m going to spend some time talking about value-form theory (also sometimes called a labor theory of value) for those unfamiliar with the analytic because the goal is not rote academic exposition but to draw out meaning and implications for all of us who are already living within structures which are fundamentally more accountable to the value-form than to life itself. The goal is clarity, to understand how sickness, impairment, ill health, debility are socially organized. The secondary goal is to enable you to imagine what could become possible when we strip away the illusions that bind us to a system that is not only indifferent to our survival but is naturalized to the point of being illegible.

Value-Form Theory (the Social Logic of Capital)

Value-form theory names a specific insight at the core of Marx’s critique: value is not a thing inside commodities but a social relation that only becomes visible through the forms it takes—money, prices, exchange. It comes from Marx’s close analysis in Capital of how capitalism organizes labor and forces human activity to appear in these strange, indirect ways. Value-form theory shows that value is produced by a particular historical system that compels labor to take the commodity form and compels wealth to appear as money.

It’s a way of making sense of why our lives end up mediated through markets, why human needs get refracted into costs and profits, and why social labor only “counts” when it can be expressed in monetary terms. Social labor refers to the labor that society recognizes as contributing to its collective reproduction—not simply work that is done, but work that is validated through the social organization of production. Under capitalism, that recognition is mediated through the market: labor only “counts” when it produces commodities that can be exchanged.

Social value, then, is the outcome of that validation process. It’s the measure of labor that has successfully entered the circuits of exchange and been acknowledged by the market as socially necessary. This is why entire realms of life-sustaining work—care, disability support, community survival—can be indispensable yet still treated as valueless: without a commodity and a sale, the system refuses to see them as part of its social labor at all.

Value-form theory insists that value is not intrinsic—it is not a physical attribute or a hidden essence within commodities. It is not a metaphysical property transferred from worker to object either. This cuts directly against the way that the luxury industries that naturalize ‘worth’ as if diamonds or designer goods simply possess value rather than having it socially conferred.

Value exists only as a social relation. It arises from the way labor is organized, recognized, and validated in capitalist society. The movement of value (its creation, realization, and expansion) is what structures social life under capitalism, often without individuals recognizing that they are participating in these processes at all.

In this framework, commodities acquire value only when they are successfully sold. A commodity that remains unsold, no matter how useful or painstakingly crafted, has no social value. It becomes waste not because of its material form but because the market did not validate it. Think of the food that rots in supermarket dumpsters while people go hungry, or the unsold clothes destroyed by luxury brands to protect exclusivity (literally treated as more valuable to burn the clothes than to have them sell for too little money), or artworks (an extremely obvious example of this is Duchamp’s famous found-object work “Fountain” which is merely a signed store bought urinal, less obvious is for example the difference between a photograph by Peter Hujar vs. a photograph also taken in the 80s by your gay uncle Peter)—each is “valueless” until exchange validates it or the ongoing absence of exchange maintains its “valuelessness.”

This runs against everything we’re taught to treat as common sense, especially in a culture that insists usefulness, effort, or beauty should naturally make something valuable. But that insistence is a farce, and value under capitalism isn’t measured by need or labor or intrinsic worth; it’s proven through the ruthless consistency with which markets ignore anything they cannot profitably circulate.

This is one of capitalism’s fundamental cruelties. The most essential goods and services can be easily rendered worthless if they are not (or cannot be) profitably exchanged. Likewise, the most trivial luxury goods can acquire extraordinary worth simply because someone with money is willing to buy them at a very high cost. The point is that value, then, has nothing to do with human need.

Money plays a central role in this process. It is not merely a handy medium of exchange; it is the concrete appearance of value itself. Money is not just a convenient token we pass around. It is the form that value has to take in order to be recognized in our capitalist society. A farmer can grow the best and most delicious strawberries, but that food has no capitalist value until the moment money changes hands. When a person’s care needs don’t generate direct profit—merely compensating the workers for their work—capitalism treats that need as a cost, rather than a moment of creating money-backed value. In other words, money is the gatekeeping girlboss of capitalism: nothing counts as socially real value unless it can be expressed through it.

Through money, abstract labor becomes socially legible. Every interaction mediated by money reinforces this social reality. When someone pays for a product or service, they participate, knowingly or not, in a structure that privileges profitability over need and accumulation over sustenance always. Money’s universality, its capacity to translate wildly different forms of labor into a single quantitative measure, is what binds society together around the pursuit of value, but it is the means not the end in and of itself.

This is why the logic of capital is totalizing. It shapes economic transitions and in so doing defines the very ways people understand time, capacity, worth, obligation, and interdependence as economic variables. It determines what kinds of human activity appear meaningful or legitimate. Tasks that reproduce life are devalued when they cannot be easily measured and commodified, and therefore are not easily rationalized. Activities that generate profit, even when destructive, exploitative, dangerous, or evil are celebrated as productive contributions to society. This basic misalignment between what life requires and what capital demands is the foundation upon which health is built and thus why it is a political category not an objective measurement of fact.

Value-form theory gives us a tool to break this illusion. By showing that value is not an intrinsic property of labor, bodies, or even health, and insisting that it is indeed a social relation expressed through money and exchange. This exposes the arbitrariness of the metrics that capitalism imposes on the body to make it legible. Bodies are illegible to the market precisely when they cannot be easily converted into profit.

Embracing this illegibility allows us to recognize our bodies on our own terms (a site of lived experience, need, and relational labor) rather than a ledger to be audited. What appears on the balance sheet as failure, weakness, decay in capitalist accounting may in fact be survival, adaptation, and unruly resilience in a world hell bent to disorganize human flourishing. In this sense, value-form analysis opens up space to reimagine our own value beyond the narrow logic and legibility-driven abstractions imposed by capital.

A dialectical analysis helps us hold this recognition without slipping into the trap of treating it as an eternal truth about bodies or health. It reminds us that the way capitalism defines value, legibility, and “health” is not natural—it’s the product of historically specific social relations. What looks like a universal law of human life is, in fact, only the temporary arrangement of a particular mode of production. Capitalism makes the body legible because it needs to manage labor power; it makes health moralized because it needs to individualize blame; it makes value quantifiable because it needs to organize extraction. None of these are timeless facts about what bodies are. They are contingent techniques of rule.

This is why we have to be careful not to universalize what is only true under capitalism. The illegibility of the body is not a metaphysical claim; it is a material response to the way capital attempts to rationalize and discipline life. In another social order—one not organized around wage labor, commodity production, and profit—our relationship to health, need, vulnerability, and interdependence would look wholly different. Dialectical thinking keeps us oriented toward this specificity: it situates each category in motion, in conflict, in history.

And this matters politically. If we mistake contingent arrangements for eternal ones, we collapse the horizon of what could be. We begin to imagine the body only through the frameworks capitalism allows, and thus we begin to imagine the future only through capitalism’s limits. But when we understand these arrangements as historically produced, we can also understand them as historically dissolvable. The contradictions between what life requires and what capital demands are not static—they are engines of social transformation. To name them clearly is not to declare defeat; it is to make space for the possibility that bodies, needs, and value could one day be organized around human flourishing rather than profitability.

Health as a Category of Capitalist Reproduction

Capitalist reproduction refers to the ongoing process through which the system regenerates itself—its labor force, its institutions, its hierarchies, and its conditions for profit. It’s not just about producing goods; it’s about producing the social relations that make exploitation possible in the first place. Wages are kept at levels that force people to return to work, industries are structured to maintain dependence on markets, and whole populations are sorted into ‘useful’ and ‘superfluous’ categories to keep capital’s needs met. In this sense, capitalist reproduction is the machinery that keeps the system’s logic—profit over life—circulating across generations.

In capitalist society, health is framed as a private matter, a personal responsibility, and a marker of both individual virtue and effort. But beneath these ideological layers lies the truth that health is valued to the extent that it enables people to work (see Health Communism for a much longer discussion of this).

The body illegible is the body unaccounted for, the body that refuses to be reduced to metrics, spreadsheets, or measures of productivity. It is the body that aches, rests, or pauses without explanation. It is the body whose needs don’t quite fit into the provided space on the forms. It is messy. Contingent. Relational. Stubbornly real, existing outside of the tidy abstractions of capital: the body illegible.

To inhabit an illegible body is to insist that life can’t actually be fully rationalized, it just is. It is to demand space for care, rest, and vulnerability in a world that demands growth, circulation, output. The illegible body insists that survival, recovery, interdependence, and presence are in and of themselves radical acts, and that human worth is not measured in dollars, nor in productivity, because the rhythms of life do not ever fully bend to the logic of capital (no matter how many abstractions you force onto the frame).

The ‘healthy’ individual in capitalism is not defined by flourishing, thriving, or even well-being. They are defined by their reliability, especially their reliability as labor-power. This ‘healthy’ individual can work regular hours, doesn’t take sick days, can withstand extended demands, recover quickly, and requires minimal support from others. This definition of health, of course, has nothing to do with feeling well, it has everything to do with the needs of capital.

Because of this, health systems are not actually designed to promote and reproduce well-being. They are designed to maintain or restore labor capacity at the lowest possible cost (again, see Health Communism). Hospitals are structured around throughput, efficiency, and risk/liability management. Insurance companies prioritize cost containment, not the delivery of financing for care. Pharmaceutical companies focus on products with a guarantee of continuous revenue, deprioritizing high need but low profit therapeutics and drug interventions. State health policy, even when couched in the language of public welfare or public health, is oriented toward managing population health in ways that first and foremost support economic productivity.

This logic also shapes what we think of as ‘preventative care.’ Under capitalism prevention is valuable when it maintains the workforce and reduces future treatment costs. It is not valuable when it challenges structural conditions that produce illness in the first place. Environmental toxins, unsafe workplaces, and chronic stress/burnout are tolerated not because we need to raise awareness of the harms, or because we lack alternatives or interventions to interrupt these harms, but because confronting them could fundamentally destabilize or even undermine capital accumulation. Health policy thus is a form of damage control for capitalism’s worst excesses rather than a vehicle of genuine social transformation.

Health capitalism is a weaponization of health. Wellness becomes a credential you must earn to be seen as responsible, worthy, or fully human. The burden is placed on individuals to ‘choose better,’ even when they’re forced to breathe poisoned air, work through pain in unsafe conditions, live without safe housing, or navigate a health system that treats them as toxic costs to be minimized. The illusion of personal responsibility is one of capitalism’s greatest and most effective ideological shields: it keeps our attention narrowed and away from the machinery that is actually killing us. It’s easier to pathologize and blame people than to admit that entire communities are sick because their lives have been organized around extraction and abandonment.

I mention this not to inspire despair, but as an invitation to stop exhausting ourselves on terrain built to blunt our efforts. Naming the limits of health policy is not nihilistic—it’s clarifying. It frees us from the illusion that we can plead or educate the system into behaving differently. You don’t convince a river to reverse course; you learn its flow, its force, and then you organize how you will move around how the water actually moves. Once we stop treating capitalist institutions of health as neutral or reformable in their core logic, we can redirect our energy, capacity, and creativity toward building infrastructures that can actually meet each other’s needs. That shift, away from appealing to power and toward collective self determination, is how we work towards real transformation rather than endlessly tending to the wreckage of boats we tried and failed to send against the current of the river.

Expanding the lens reveals what this rhetoric works so hard to obscure: health is not an achievement—it is an environment, a set of material conditions. When we treat health as a personal accomplishment or failing, we erase the violence of housing policy, labor conditions, food systems, environmental destruction, policing, and mass incarceration. Illness then appears as a shortcoming instead of as a predictable outcome of deprivation, overwork, and abandonment. Reframing health as a collective infrastructure is a refusal to let health capitalism define our collective struggles as individual faults. We need to reclaim the truth that our bodies are shaped by the world we’re forced to survive in.

Illness as Social Devaluation

Illness (chronic or episodic) disrupts the artificial rhythms that capitalist society depends on. It interrupts the linearity of work, the predictability of scheduling, and the command structure of hierarchical workplaces. Because capitalism mostly requires bodies to be relatively stable instruments of labor, illness is experienced as both a physical state of the body but also a form of social rupture.

One of the first ways this rupture is felt is through time. Capital demands that workers adhere to standardized, predictable schedules. Illness refuses this order. It introduces wild variability. These fluctuations, particularly their categorically unpredictable nature, do not align with capitalist expectations of a worker’s body.

At one of the few jobs I held before I became too sick to work, I had paid sick leave—on paper. Every month I’d take a single half-day for my infusion, clocking out early on a Friday so I could start the six-hour treatment before evening. Shifting it from 6 p.m. to 1:30 wasn’t a luxury; it was the only way to survive Saturday’s second infusion and still have enough strength on Sunday to wash my hair, reset my body, and show up on Monday. I used sick time to be dependable. But the regularity of it—precisely the thing that allowed me to manage my illness and remain a “functional worker”—made my boss wary.

I was hauled into a meeting and asked to justify my own treatment schedule as if reliability itself were evidence of deceit. Did I really need to have an infusion monthly, could I have treatment every other month instead? In capitalism’s calculus, you’re punished either way: unpredictable sickness is a threat, and predictable sickness is a conspiracy. Either way, the sick body is treated as suspect. Employers often describe chronically ill workers as “unreliable,” a word that captures the moral judgement embedded in capitalist time. The problem is not that people are sick; the problem is that their sickness cannot be synchronized with the needs of production (and when it is, that is treated as clear evidence of time theft from the boss).

Illness also reduces a person’s capacity to generate surplus profit, which means that their social standing changes. In a society where formal employment is the primary mechanism for accessing housing, insurance, income, and social recognition, illness becomes a pathway to dispossession from the body politic.

The first thing most people ask when you meet them is: What do you do? Not who you love, not what makes you happy, not what kind of world you want to live in—but what your job is. The answer to that question has become shorthand for who we are and what we are worth. A steady paycheck is treated like proof of character, and losing a job is treated like a kind of personal failure. For chronically sick people, this question lands differently: What do you do? can mean… Are you useful? …Do you deserve care? …Housing? …Life itself?

The seemingly innocuous question, “What do you do?” carries the weight of moral judgement. Work has become a shorthand for identity, morality, and worth so that people are defined not by who they are but by how productive they are. This cultural assumption shapes schools, families, media, and public policy, creating a pervasive pressure to perform economically or be abandoned and discarded as if you are disposable.

At a psychological level, illness (even if only episodic or temporary) exposes the fiction of self-sufficiency. Humans are interdependent, yet capitalism relies on the myth that individuals sustain themselves through their own labor. Illness brings interdependence into the open, revealing how deeply we rely on others for survival. This revelation destabilizes capitalist ideology, which is why society often responds with resentment or denial. The sick person becomes a reminder of vulnerability that capitalism works hard to suppress.

Against Legibility

The purpose of value-form analysis is not to wallow in structural critique, or dazzle with a display of pedantry. Its purpose is clarity. To bring clarity to the set of conditions that govern our lives in order to make collective transformation become thinkable. The most incisive critiques of the value-form come from disabled and chronically ill people, the sickos. Our experiences—and our embodied knowledge—are evidence that we will only get free when we first learn to sever worth from productivity.

Disability justice movements have been articulating this critique and horizon for two decades. Their work prefigures a world where infrastructure is built around human need, where access is not afterthought, where care is a shared responsibility, never understood as an “economic burden.” Those who live with fatigue, pain, instability, or fluctuating capacity understand that time is not linear. That the body’s needs do not obey the market. That survival requires networks of other sick folks all around the world passing resources to one another without expecting anything in return.

A world organized around value will always for legibility on our bodies, and privilege the bodies that produce profit, while neglecting those that do not. It will always treat illness as deviance, disability as waste, and care as a cost. It will always abandon people precisely when they most need support.

But this deliberate choreography of abandonment reveals the limits of the capitalist political economy—it simply cannot do what many people want it to do. The body illegible exists at the point in the horizon where capitalist ideology collapses. Our lives are evidence that the idea of self-sufficiency is a fiction, and proof that it is impossible to organize society around surplus profit while claiming to care about human well-being. The body illegible embodies the failures of the political economy but also its potential transcendence.

To build a world beyond value is not to retreat into utopian abstraction (though there is never anything wrong with utopian thinking in my opinion, as Madeline Lane-McKinley writes in her recent book Solidarity with Children, all utopias are problems, and a utopian problem “...confronts our own unfreedom to imagine.” As Eduardo Galeano writes, “Utopia lies at the horizon. When I draw nearer by two steps, [utopia] retreats two steps. If I proceed ten steps forward, it swiftly slips ten steps ahead. No matter how far I go, I can never reach it. What, then, is the purpose of utopia? It is to cause us to advance.”1). A world beyond value is a commitment to the ordinary, the gritty relational work that chronically ill and disabled people perform every day which offer a glimpse of what freedom might mean in a world governed by mutual obligation, collective care, and shared life.

The challenge is always not to simply critique the systems that harm us, and then rest on our laurels satisfied at having been proven right about the worst, most toxic aspects of our culture. The challenge is to build. Build now, not after some theoretical revolution at some point in the future, now. We must continue to build things where the fragile, the sick, the unstable, and the interdependent—who is to say that is not all of us?—are recognized as the core of the social world. Life itself must be treated as more than a means to an end (accumulation).

The horizon, which, “...swiftly slips ten steps ahead,” is a demand made urgent by every body longing for ease, every person forced to fight for survival, and everyone struggling for even the smallest act of care within a system that refuses to care at all. To take illness and disability seriously is to admit that capitalism has no future worth preserving. And it is in that honesty that liberation begins. Let us continue to proceed ten steps forward, as Mariame Kaba likes to say, “keep it moving.”

As cited in Lane-McKinley’s Solidarity with Children: Eduardo Galeano, “Window Utopia,” in Walking Words, trans. Mark Fried (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 326.

This was so well-written! Legibility assessed by value form theory, it worked so well. Thank you for sharing. It reminded me of an essay I read recently. You may have already read Zoe Belinsky's 'Transgender and Disabled Bodies: Between the Pain and Imaginary'. As I understand, Belinsky addresses the debilitating forces of capitalism that obfuscate social reproduction (and pain) from labor in the disabled and trans bodies. I'm grateful to have read the two together so recently. Legibility under value form seems to be exposed as another obscuring factor of capitalism to prevent us from reclaiming labor that moves away from pain and towards the imaginary, or closer towards a universally accessible utopia.

This really resonated with me and is beautifully punctuated with the photographs. I've restacked it with a long note for future reference...thank you x